AS HELENSBURGH has developed over the years, not always for the better, so too has Shandon.

It is a good example of a community where changes have been especially pronounced, with the loss of many features.

This ranges from removal of its pier to closure of the church, school, railway station, sub post office, shop, hotel, and golf course.

Local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre investigated the community’s history, and he began by looking at the rise and fall of Shandon Pier and the story of Shandon Church.

He says that, as land became available for house-building at Shandon from the 1830s onwards, the location proved to be extremely attractive, and uptake was swift.

Before very long, a number of some substantial villas were built, and the population swelled.

While occupation by the owners was in some cases only seasonal, such houses and their policies required sizeable numbers of staff.

There had for some time been a road beside the Lochside, but with ongoing growth in Victorian times, it proved to be liable to deteriorate quickly, particularly in bad weather.

The surface was often muddy, there were steep gradients in places, and there were several bends to be negotiated.

With ever-increasing wheeled traffic, the road became notorious, and there were harrowing accounts of horses becoming bogged down in the mire.

A typical account from 1875 refers to a lorry, which “though pulled by a powerful horse and trace horse, became stuck up to the naves when coming up the brae at Berriedale — it was detained for a considerable time”.

It was not surprising that in the wake of Henry Bell’s pioneering steamboat ‘Comet’ of 1812, water-borne transport soon beckoned as an alternative to the mud and dangers of the road.

By the early 1820s, vessels such as the Henderson and McKellars steamship ‘Sovereign’ were plying the Glasgow-Gareloch run.

Good piers on the Gareloch were lacking, and so at a number of places like Shandon and Garelochhead, a small ferry-boat would row out to rendezvous with the steamboats.

Some of the early steamers additionally towed a small boat of their own.

The ferryman at Shandon from the early days of feuing was Duncan McKinlay, and he plied his craft faithfully for some 50 years.

Such an arrangement was always going to carry an element of risk, and in 1859, when his small craft approached the steamer ‘Gem’, it hit the larger vessel and capsized.

Passenger Alexander Davidson, gardener to George Martin, was drowned. Such an outcome, tragic though it was, was probably exceptional, and the existing arrangement continued as before. It was not until 1878 that a major change took place.

Following the sale of Robert Napier’s very large residence, West Shandon, after his death in 1876, it opened as Shandon Hydropathic Establishment (above) in 1877. This change acted as a catalyst for the building of a pier close by.

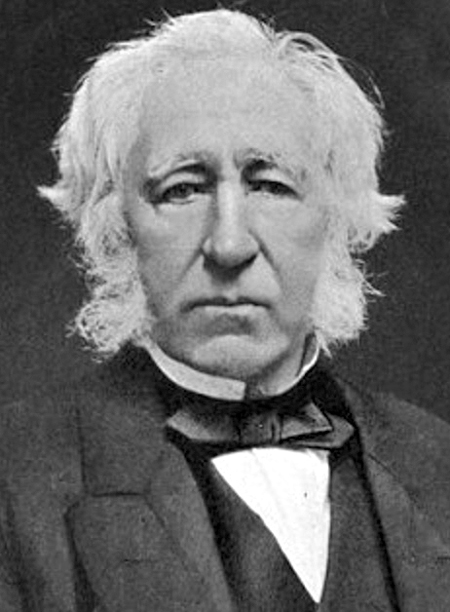

Given the ambitions of Napier (left), and the great and the good he entertained at his residence, it was surprising that he had not used his influence to build a pier in his own lifetime.

Given the ambitions of Napier (left), and the great and the good he entertained at his residence, it was surprising that he had not used his influence to build a pier in his own lifetime.

In fact, according to an article in the Dumbarton Herald of 26 July 1878, this matter had been discussed between Napier and Sir James Colquhoun, “but at Mr Napier’s request, Sir James forbore from carrying out the project”— a surprising decision.

With the arrival of the Hydro, and the focus on commercial success, momentum built up with typical Victorian drive and commitment.

The pier was built under the auspices of the Colquhoun Estate Trustees, and the opening took place in September 1878. It was opposite the old toll-house, and close to the premises of the 20th century firm of Timbacraft.

Built by Baillie Kennedy of Partick, the pier was 275 feet long, and had piles of the best pitch pine, with construction geared towards protection from marine boring worms.

The pierhead face was rounded at the outer corner edges to facilitate berthing and departure by steamers without damage to the structure. There was a commodious waiting-room, and there was even a special slip for the landing of horses and cattle.

It was known as either Balernock Pier or Shandon Pier. To mark the official opening, the well-known steamer, the ‘Balmoral’ paid a call, “gaily decorated with flags, bunting and evergreens, in honour of the occasion”.

Although a great convenience for visitors to the Hydro, the pier was some distance from the centre of Shandon, but as steamers continued to use the ferry call as well as the new facility, there was not too much discontent.

However, after the opening of the Craigendoran railway station and piers by the North British Railway Company in 1882, it was decided to discontinue the ferry call at Shandon.

This upset many Shandon residents, and pressure grew for the erection of another pier in place of the ferry call. The upshot was that in 1886 a new pier opposite Shandon Free Church was opened.

Spearheaded by local residents Henry Bell, namesake but not relative of the steamship pioneer, William Brown, John Kerr, Andrew Henderson, Andrew Kilpatrick, William Swan and William Walker, the new facility was paid for by several sponsors.

It was then made over by them to the Colquhoun Estate Trustees as part of their estate, and to be maintained by them on the same basis as their other Gareloch piers.

Built at a cost of around £1500 by Messrs Watt and Wilson, the designs were by Glasgow-based William Robertson Copeland, who also designed several of the local reservoirs.

The new facility had piles of greenheart, which is a durable South American hardwood, pierhead facings and copings of elm, and the gangway and terminal platform had creosoted pitch pine. At the pierhead was a roomy waiting room, along with piermaster’s office and storeroom.

The North British steamer Dandie Dinmont at Shandon Pier.

There was a condition that with the “exceedingly handsome” new Shandon Pier now in use, the Colquhoun Estate Trustees would close Balernock Pier, a measure aimed at preventing the unpleasantness of possible litigation.

Given that the latter was still in almost new condition, one might imagine that the owners of Shandon Hydro would hardly have welcomed this outcome. What is not known is whether or not Balernock continued as a private pier or required to be demolished.

Old photographs seem to show two piers close to the Hydro, and there were certainly adverts which referred to yachting and boating from a private jetty. An Ordnance Survey map from the turn of the 20th century shows Balernock Pier, but it has an accompanying description “Disused”.

Shandon Pier did not enjoy a long and distinguished life: it closed as a public pier in 1915, possibly influenced by the arrival around the same time of a new Gareloch Motor Service, operated by Messrs McLaren, though other factors, such as wartime circumstances, may well have played a part.

However, although the pier was rendered redundant as a public facility, it did continue to be used by the crews of laid-up ships moored in the loch, until the onset of the Second World War.

This was however not quite the last chapter in the story of the Shandon piers. In 1942 wartime restrictions led to the closure of the Gareloch steamer service, by which time the venerable ‘Lucy Ashton’ had been the only vessel plying the route.

However, that same year, a newspaper report revealed that Messrs Ritchie Brothers, Ferrymasters, Gourock, were planning to commence a new ferry service, billed as running between Rhu and Rosneath. It was claimed that there had been many complaints about the old service.

In October 1942 it was announced that the new service would in fact run between Clynder and a newly-built pier at Gullybridge, although it was still sometimes referred to as the Rosneath ferry.

Launches would be used, and it would be a passenger only facility, as had been the case with the railway steamers.

The new service began, but by May the following year, the Chief Constable was reporting problems to Dumbarton County Council — the timetable was not being adhered to.

The Chief Constable stated that Ritchie Brothers were not willing to continue the Shandon steamer service, then run between Clynder and a newly-built pier at Gullybridge, and the suggestion was made that the County Council should take over.

The chairman of the County Council suggested that perhaps either the Naval authorities or the Ministry of War might consider running the service, and it was agreed this possibility should be investigated.

The outcome was that Ritchie Brothers continued to run the ferry with the aid of a Government subsidy, but, with the withdrawal of this support in 1946, they once more announced they would be giving up.

All was seemingly not lost, however, when it was disclosed later in the year that a Mr Fleck had agreed to take over the ferry.

Unfortunately, it turned out that this was conditional on his being able to berth at Rosneath Pier, and in December 1947 the service came to an end, because the Ministry of Transport would not agree to this arrangement. It was the end of an era.

The presence of Gullybridge Pier thereafter provided an unofficial amenity for other than travellers.

For quite a few years, it was the habitual haunt of numerous sea-anglers, and it was unusual to pass by and not see a cluster of anglers sitting patiently at the end of the pier.

With the major programme of road widening and straightening of the main road between Rhu and Faslane in 1969-70, virtually all traces of the pier were erased.

Shandon pier had closed as a public facility in 1915, but it continued to be used by the crews of laid-up ships moored in the loch, until the onset of the Second World War.

Shandon takes its name from the Gaelic name ‘sean dun’, meaning old stronghold, a mediaeval fortification on the hill slope above Balernock.

Today there is little to see there, but another place name not far off, Tom a’ Mhoid, hints at the status of the one-time occupant of the fort as it translates as “hill of justice”.

This dates from the days when the lord exercised the power of pit and gallows over those in his domain. Some believe that the Earls of Lennox had one of their early residences there.

Just down the hillside, near Carnban Point, a truly palatial residence was built in Victorian times, worthy of the mightiest prince, certainly in terms of its size.

This was West Shandon, erected in 1851 for leading Clydeside engineer and shipbuilder Robert Napier.

Napier had already had a presence there for quite some time. He had acquired a site in 1833, with the first residence being initially referred to as Westburn of Carnban.

By the time of the 1841 Census, the name West Shandon was being applied to the then structure, to avoid confusion with the nearby Shandon House.

On that occasion, several family members were present, including Napier’s wife, Isabella, as well as servants, although Napier was not at home.

This sizeable household would seem to imply that the habitation, as it was at the time, was relatively substantial. Around this time, Napier was also buying large acreages of land in the vicinity.

With the start of work on the new West Shandon, designed by the architect J.T.Rochead in the Scots-Jacobethan style, it quickly became clear that Napier’s ambitions for the site were breathtaking in their scope.

No expense was spared. As local stone was not considered suitable, supplies of the finest sandstone were sourced at Bishopbriggs, and brought in via the Forth and Clyde Canal, an enormous undertaking in its own right.

This was in an era before the advent of the famous Clyde puffers, so the craft used to transport the stone, and other materials, would probably have been gabbarts, small sailing vessels, with the capacity to beach at high tide, while remaining upright on the ebb.

The stone would then have been removed to the site by horse and cart.

Construction was not complete until 1863. The total outlay was £130,000, a vast sum at the time, though that figure included fittings and furniture, along with the extensive collection of Old Masters paintings, china and glassware, antiquities, and extensive library.

There were also walled gardens and greenhouses, and large vineries.

This would have demanded an equally impressive number of staff just to keep the place running.

Many people eulogised about this new feature in the landscape. David Napier, in his “Life of Robert Napier of West Shandon” (1904), refers to the house as “one of J.T.Rochead’s happiest creations”. However, not everyone was so favourably impressed.

Hugh McDonald, a favourite son of Glasgow, made some critical comments in his classic work “Days at the Coast” (1857). While freely acknowledging Napier’s first-rate talent as engineer and shipbuilder, he was less impressed by his tastes in architecture.

He wrote: “This castle of his — a grim-crack house-of-cards kind of affair — is an eyesore to every ‘voyageur’ on the loch which it disfigures, and to the scenery, of which it is totally out of keeping.

“Had it been couched on a spacious lawn and half-hidden by stately trees, it might barely have been tolerated, but projected naked on the loch as it is, it is really too much for the patience of any mortal who possesses even a spark of taste.”

Many people came to see West Shandon. According to Napier’s biographer, “Almost every person of note who came to the West of Scotland called upon him.”

Napier’s biography names only one visitor — Princess Louise — who called shortly after her 1870 marriage to the Marquis of Lorne with her husband. The author stated: “Her Royal Highness was so delighted with her host that she sent him her photograph as a souvenir.”

Napier was in the habit of giving female visitors a so-called “Shandon Salute”, which entailed giving them a kiss on the cheek, and this seems to have been given to all.

Napier appears to have been a model host. The author of “The Story of Helensburgh” (c.1894) — anonymous, but generally understood to be George McLachlan, the long-serving Town Clerk of Helensburgh — commented: “To multitudes, it was a delight to visit Shandon House (sic), and be conducted by the owner through his rare collection of paintings, antiquities and curiosities, many of them full of historical and antiquarian interest.

“The present writer remembers when he was a young lad, how courteously and kindly he was received by the great engineer, and the interest taken in his prospects.”

As Napier grew older, he devoted more and more of his time to showing visitors round his house and policies.

One possibility is that among the visitors may have been explorer and missionary David Livingstone.

J.Arnold Fleming, the author of “Helensburgh and the Three Lochs” (c.1957), confidently asserts that Napier “was a generous benefactor of David Livingstone, whom he entertained as his guest when in this country.

“In gratitude for such kindness, this great explorer fetched to Shandon exotic plants that flourished in the greenhouses which Napier constructed to receive them.”

Elsewhere, he noted: “David Livingstone, when passing through Helensburgh on his way to being the guest of Napier at Shandon, would recall that here Zachary Macaulay was educated.”

It is certainly the case that Napier did support various causes close to his heart, and Livingstone’s endeavours may well have been amongst them. Several sources imply a friendship between the two.

Napier’s biographer — who was related to him — quotes a letter sent by Livingstone. Napier had evidently invited Livingstone to witness the launch of the Ozman Ghazy, a vessel built and launched on the Clyde in 1864 for the Turkish Navy.

In reply, Livingstone sends his apologies, but commented: “I should very much like to see an ironclad performing under your superintendence. If possible, I shall be at the trial trip of Ozman Ghazy on Wednesday.”

Revealingly, the letter goes on to mention the death of Livingstone’s mother, along with some personal details. Such comments imply friendship.

Former navyman Charles Addis, who was based at Faslane in the 1960s, carried out a good deal of investigation into the history of Shandon.

This led him to understand that David Livingstone planted a Giant Sequoia tree at West Shandon, while Napier planted a Cedar of Lebanon, possibly on the same occasion.

He noted that the trees were originally fitted with explanatory metal plaques, but in the fullness of time, these were purloined by tourists as souvenirs, rendering proof of association virtually impossible. There remain several Sequoias in the vicinity to this day.

Something else that hints at a link was a visit to West Shandon by Henry Morton Stanley, whose name is forever linked to Livingstone through their famous meeting in Africa.

Stanley was one of those larger-than-life characters who leap out of the pages of history. Of Welsh stock, and born out of wedlock as John Rowlands, he emigrated after a difficult childhood to the United States in 1859, at the age of 18.

Disembarking at New Orleans, he met up with businessman Henry Hope Stanley when searching for work.

Stanley helped set him on his feet, and in gratitude, Rowlands changed his name to that of Henry Stanley. The Morton middle name was added later. His life thereafter was a colourful one, and by the time he met Livingstone, he was famous in his own right.

The visit to West Shandon took place in November 1872. Stanley arrived in Helensburgh by train from Glasgow, where a carriage was waiting. He arrived at West Shandon for lunch, when toasts included “Dr Livingstone”.

Back in Helensburgh, Stanley had dinner at Ardlui House, hosted by Provost Thomas Steven. He also found time to deliver a lecture at the United Presbyterian Church in the town.

With the death of Robert Napier in 1876, the house and contents were sold off. The aggregate proceeds from his estate were put at over £400,000.

The story of West Shandon always seems to focus solely on the great engineer, with virtually no mention of his family who remain effectively invisible.

Napier’s wife, Isabella Napier, was his cousin, and was born at Rosneath in 1793, the daughter of John Napier and Ann McAllister. The family appear to have been fairly affluent. The wedding took place at Dumbarton in 1818.

Robert and Isabella went on to have seven children: Ann, born 1819; James, born 1821; John, born 1823; Jean, born 1825; Isabella, born 1827; Robert, born 1829, and David, born in 1832. The couple experienced family misfortune: David died as a baby, while Robert died aged 19 years.

Although little has come to light about Isabella, the marriage appears to have been a successful one. Following her death in October 1875, Robert seems to have been grief-stricken, with his own demise taking place the year after.

In 1877, following extensive alterations and additions, the massive West Shandon took on a new life as Shandon Hydropathic Establishment. Such enterprises were very fashionable at the time.

Lists of paying guests were often published in the local press. These reveal that although many came from the West of Scotland, a significant proportion came from other parts of Scotland as well as quite a few from south of the Border and abroad.

Among the multitudes who flocked to the Hydro was Robert Louis Stevenson, who was in residence, along with his parents, from April 5-14, 1879.

At that time, Stevenson was still finding his feet as a writer and he could be described as a classic example of the rebellious son.

His parents desire was that he should follow in the great civil engineering tradition of his justly acclaimed forebears.

But the young Robert showed no interest, so he was put to studying law. This field likewise held no appeal. His attitude led to serious friction between father and son.

At the time of the Shandon visit, Robert’s emotional life was also in turmoil from a different quarter. In 1876, while travelling in France, he made the acquaintance of Fanny Osbourne, an American lady who was separated from her husband, and soon they fell in love.

This further strained the already fraught relationship between Robert and his parents, but tension subsided in 1878, when Fanny returned to the United States. This was the backdrop to his stay at the Hydro.

Stevenson’s mindset can be gauged from a letter he sent while there to Fanny Sitwell, an old flame from further back. The contents are quoted in ‘The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson’, edited by Booth and Mayhew (1995).

He wrote: “I am staying with my people at Shandon Hydropathic Establishment. I hate it, and am dull, stupid, and a little wee bit gloomy between whiles. When I cannot work, cannot walk, and am not much in the humour to read, my time hangs upon my hands.

“I think I’ve never felt so lonely as when I am too much with my father and mother, and I am ashamed of the feeling, which makes matters worse.”

That August, Stevenson left Scotland to meet up with Fanny Osbourne in the United States, marrying her in 1880, by which time she was divorced from her first husband.

The great influence of Shandon Hydro, and its many attractions, could be seen as threatening to shift the centre of gravity of Shandon away from the cluster of amenities which included the church, school, pier, grocery, and penny savings bank. Almost certainly because of the Hydro, the first public pier in Shandon was located close by.

Given the many paying guests at the Hydro, their presence must have generated a need for a place handling mail, so the decision to open a post office nearby made good business sense.

The exact date of the opening of Shandon Post Office (right) has not been pinpointed, but it was probably not long after the opening of the Hydro. It was certainly in existence by 1883, when Mrs Hanagan was postmistress.

The location was an unusual and picturesque one too, by the old lodge-house to West Shandon, and many photographs survive.

By the end of the decade, Mrs McLean was postmistress, and she remained there for many years — until at least 1937. The next postmistress going into the Second World War was Miss E.S.McLean, possibly a relative.

The Hydro was commandeered by the military in both World Wars, but the post office survived both conflicts. Doubtless the military presence would have generated its own demand for mailing services, and there is still a post office at the Clyde Naval Base at Faslane.

The sporting amenities at the Hydro were essentially for the use of guests only, but at times of recession, a number were made available for non-hotel guests. A likely candidate would have been the nine-hole golf course.

That would certainly have been the case from around 1930, when Shandon Golf Club came into being, replacing control by the Hydro. Originally opened in 1890, the course was redesigned not long after by the famous Willie Fernie, and it proved a popular attraction.

The terrain was hilly, but the views were outstanding. Celebrated golfer Tom Haliburton from Rhu learnt to play the game there, and many members came from outwith Shandon.

Crucially, the course (above) was not owned by the club, and this ultimately was a major factor in the winding-up of the club in 1958. The farmer on whose land it was located stated that he needed to have his land back. A campaign to save the course was unsuccessful.

Shandon Omnibus Station was based at the Old Tollhouse, by Carnban Point. A toll-bar operated at Shandon from 1830-57, when it was replaced by one at Garelochhead.

The Omnibus service started around 1868, and the driver was Robert Hosie. An advert from 1883 refers to an omnibus setting out daily at 7.50am, in good time for travellers to catch the 9am train from Helensburgh to Glasgow. A return run set off from outside the railway station at 6.15pm.

There is no mention of a service in between, with the service as advertised primarily aimed at those commuting to and from the city.

It is not known if the service adjusted in any way to suit those journeying to and from the Hydro. It had its own coaches for hire, though to what extent they ran a transport service to suit paying guests is not clear.

The Shandon Omnibus Station did not survive the turn of the century, and possibly competition from other forms of transport played a part in its closure.

One example is the West Highland Railway, which opened in 1894, with Shandon being one of the beneficiaries.

Shandon Railway Station (above) was typical of other stations on the line, being a handsome and distinctive building constructed in the Swiss chalet style, with shingled wall facings.

It had an island platform, and it was equipped with a signal box and points. There were sidings and a loading platform. As it had its own stationmaster, an attractive house was provided for him.

The first stationmaster was James B.Shedden. Houses were also provided for signalmen and those charged with maintaining the track and fences.

It all sounds very alluring, but one disadvantage, in common with all Garelochside stations, was that going to it entailed a testing uphill walk.

A contemporary writer put it: “A sound heart and lungs and experience of hill climbing are essential to a man who hurries from his breakfast table to catch a train at one of the lochside stations — it is easier to go to a pier.”

Perhaps the choice of location within reach of Shandon Hydro was influenced not so much by the existence of that place, but rather because a station further to the south would have entailed an even steeper climb.

One writer commented that the lofty elevation of the line came about because of pressure from some feuars, who did not wish to have a railway passing close to their residences.

While that may well be true, another reason for the inconvenient location of the stations stemmed from the fact that the West Highland Line was built on a relatively shoestring budget.

This ruled out the use of long tunnels, and with Whistlefield Hill having to be surmounted, the route north of Craigendoran junction needed to build up sufficient height to clear it, while avoiding excessively steep gradients.

By 1904, the stationmaster was Thomas Anderson Lyon. In July of that year there was an accident near the station, which, though serious enough, had the potential to have been much worse.

The safety record of the West Highland Railway, with its single track line, has been good, but over the years, incidents did crop up from time to time.

On this occasion, the carriages of a northward bound passenger train had been uncoupled from the engine, while the driver undertook to take a horse-box along to the sidings at the station.

But the brakes holding the carriages proved insufficient, and they began to roll downhill towards the station. The engine driver saw what was happening, was faced with a difficult decision.

One major consideration was that if the carriages — which contained a good number of passengers — picked up enough speed, they might derail, with possibly catastrophic consequences.

He decided that the lesser of two evils was to let the carriages run into the horse-box and engine before they built up too much speed. In the collision that followed, the leading carriage and horse-box were badly damaged, and a number of passengers suffered nasty, but not life-threatening, injuries.

At some stage, the post of stationmaster at Shandon was discontinued. When John Dewar was appointed stationmaster at Garelochhead in 1942, he was told that he would also have the stations at Shandon and Whistlefield in his remit.

This was an especially demanding time. With the construction of Military Port No.1 at Faslane in 1941-42, a branch line was built to service it, with 22 miles of track and extensive sidings.

A major factor in the choice of Faslane for the port was the existence of the West Highland Railway. In addition, the wartime presence of large numbers of other military personnel entailed yet more railway activity.

Further business stemmed from local Prisoner of War camps established as the Second World War drew to a close. Many of the German prisoners travelled daily from local stations to Inveruglas, where they were put to work on construction of the Loch Sloy Hydro-electric Power Station.

Post-war, all seemed set for a bright new future at the station. At one time, there was an annual competition for best-kept stations, and although Shandon no longer had its own resident stationmaster, it performed well.

In 1959 Shandon Station, along with those at Helensburgh Central, Garelochhead and Cardross, was awarded the First Class designation. This brought with it a prize of £7-10/-, a tidy sum.

Competition between stations helped keep up high standards, and many will recall the fine floral displays. The stations were cheerful, friendly places.

However, post-war society was changing, and with developments like increased car ownership, movement of freight by road, overseas holidays, effects of inflation, and lack of investment, railways began to suffer.

In the wake of the infamous Beeching report of 1963, it was announced that Shandon would be one of the stations that would lose their passenger service.

This led to job losses, although at Shandon, the services of a signalman, which often entailed his wife working a two shift system, were retained.

However, this too was discontinued in 1967, and the station, signal box and island platform were removed. Shandon Station became just a memory.

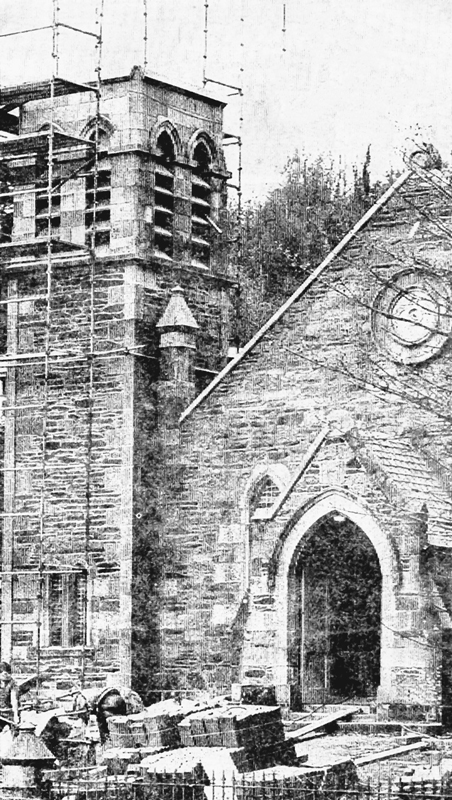

Shandon Church owed its birth to the great schism in the Church of Scotland in 1843.

Known as The Disruption, it came about because of severe tensions within the Church, particularly over the issue of patronage — should the power to appoint new ministers lie with the landowners (the heritors), or with the congregation?

With almost half the ministers leaving the Established Church to form the Free Church of Scotland, the strong belief within the new denomination was that this right should lie firmly with congregations.

The then minister at Rhu, the Rev John Laurie Fogo, remained within the Church of Scotland, carrying most of his congregation with him, but there were supporters of the Free Church in the district who decided to form their own church.

Adherents initially met in a granary forming part of the distillery at Aldownick, Rhu, in 1843, and just a year later, Shandon Free Church (above) opened its doors. It was a sturdy, but relatively plain building, designed by the architect John Burnet.

The Rev Neil Brodie was appointed the first minister. Previously he had been minister at St Andrews, Kilmarnock, and had initially remained within the Established Church after The Disruption, but his conscience subsequently induced him to demit his charge there.

Rhu itself never had a Free Church, and so Shandon enjoyed a relatively large catchment area.

Mr Brodie proved to be an energetic and forward-thinking minister, and with the support of the Kirk Session, a school, along with schoolmaster’s house, was opened the following year, not far from the church, again designed by Burnet.

With both church and school in operation, they helped form a real focal point for the ever-growing community. The manse came later, in 1864.

It must be significant that when a pier was built in 1886, it was located almost opposite the Free Church.

In 1882, the Rev Hugh Miller became minister, and proved to be a dynamic force in the life of church and community.

The Church itself was transformed into a much more imposing building the year after, with the addition of tower, transepts, stone porch and buttresses, designed by architect William Landless.

It was also around this time that Mr Miller helped form the Shandon Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Society. This type of organisation was being established in many other local communities in Scotland.

They often developed into highly influential bodies, once more helping to give a sense of community wherever they arose. The one at Shandon was still in existence when the Second World War broke out.

In 1900, the Free Church nationally joined with the United Presbyterians to become the United Free Church, so the church was now known as Shandon United Free Church.

An even more momentous national event took place in 1929, when the United Free Church joined with the Church of Scotland.

The idea of linking Shandon and Rhu churches had been talked about as early as 1925, almost certainly stimulated by the fact there was a vacancy for a minister at Shandon at the time.

However, the vacancy was subsequently filled, and the merger plan dropped. The 1929 union resulted in there being two Church of Scotland places of worship within a relatively short distance of one another.

However, both had ministers and congregations in place, and so they continued to function as in the past.

It was probably inevitable that a merger would take place eventually, and in 1954, following the death of the then minister at Shandon, the Rev George Bennett, this took place.

Even so, Shandon Church of Scotland was not rendered redundant, and services still took place, taken by the Rhu-based minister.

A major crisis in the life of the building came in early 1981, when it was disclosed that the fabric of the church was suffering from dry rot.

The estimate for dealing with the rot and carrying out the re-slating work was put at £15,000.

Dumbarton Presbytery backed the decision to close. The congregation at this point numbered 75 people.

The building was put up for sale, and after comprehensive re-working, including the removal of much of the steeple (left) , it was converted into four luxury homes in 1984.

The building was put up for sale, and after comprehensive re-working, including the removal of much of the steeple (left) , it was converted into four luxury homes in 1984.

The story of what was built in 1845 as Shandon Free Church School is also worth telling.

The momentous Education (Scotland) Act of 1872, which made education compulsory for all those aged 5-13, had a big impact upon the school.

All churches run by the Church of Scotland and those of the Free Church of Scotland now came within the orbit of the state system.

The school was designated Shandon Public School, and it went on to flourish for many years.

In the 20th century, small one-teacher schools often had female teachers. In the 1920s, Miss Campbell taught the pupils, and in 1931, Mrs Margaret Willan became schoolmistress.

She had taught for the previous 12 years at Glen Fruin School, and it was quite common for teachers to move from one small school to another, often not too far from the previous one.

The little school was threatened with closure in 1938, but it gained a reprieve. The entry for Shandon in the Third Statistical Account of Scotland gives 1949 as the date of closure.

Post-war, schools like this were re-designated, so in the later years, it became Shandon Primary School.

It was around this time that many small schools in the area closed their doors for the last time, including Glen Fruin School and Glen Mallan School.

By now roads and road transport made it more cost-effective for pupils in scattered areas to be taken by bus to bigger centres of population, and so to bigger schools.

However, a school is always a focal point for any community, and many regret the closure of such amenities, a process which continues up and down the country to this day.

One poignant reminder of the former Shandon School remains. Beside a headstone to members of the Walker family at Faslane Cemetery, there stands a smaller memorial.

It bears the inscription: “In memory of Mary and Heather from teacher and pupils of Shandon School.”

The main headstone reveals that Heather was laid to rest in 1941, aged six years, while Mary died in 1943 at the age of ten years.