GLEN DOUGLAS is best known nowadays as the home of a NATO ammunition depot, but in days gone by it was a thriving community with its own school.

The story of the isolated country school is not unlike a person — a protracted difficult birth followed by challenging early years, with maturity a much more settled period, but then unforeseen developments led to its demise.

Local historian Alistair McIntyre, a director of Helensburgh Heritage Trust, is a former pupil, and he has researched the history of the school (right), with help from a number of people, in particular Mary Haggarty of Arrochar and Ian McEachern of Luss.

What he has written paints a vivid picture of education in the landward area of the Helensburgh district through the years.

Glen Douglas has a distinctive setting. Lying at an altitude of around 500 feet and flanked by high hills, the bed of the glen is relatively flat, but at both ends the single-track road plunges very steeply, to Loch Lomond on the east and Loch Long on the west.

As a result it has never attracted much traffic from the busy lochside highways, and is cut off from surrounding communities.

There was a scattering of homesteads in the glen, and the setting meant that parish schools, like the one at Luss, were effectively inaccessible to any child living in the glen.

As the centuries rolled on, there arose a gradual awareness of the benefits of universal education, and a pioneering school was eventually set up in Glen Douglas in 1727, through the Scottish Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge.

Formed in 1709, the society’s original aim was to promote the spread of the Christian message to outlying areas, especially in the Highlands and Islands, by means of a network of schools. Over time, this was extended to include the teaching of reading, writing and arithmetic.

Against this background, the first known school in Glen Douglas took shape. In this pre-improvement agricultural era, there were around 13 settlements, with another four nearby. Some of these would have contained several households.

The teacher appointed to what was described as a ‘petty school’ was John McAusland. The location of the school is unknown, but it was a humble structure with drystone walls and thatched roof, probably an adaptation of a barn or outhouse at one of the farms.

What is known is that the teacher resigned the following year. His replacement in 1729 was Andrew McLelland, described as not having his commission because of poor arithmetic, although he did subsequently succeed in gaining the necessary qualification.

In 1839 the Rev Robert Carr, minister at Luss, wrote: “The inhabitants of the upper part of Glen Douglas are too far from any of the schools in the parish to send their children to them. The number of families affected is four.” So the SSPCK school was no longer in existence by that date.

After the ground-breaking Education (Scotland) Act of 1872, education was made compulsory for children aged 5-13, with a national system of parish school boards set up to implement and manage this objective.

In Glen Douglas, this gave rise to real challenges. The location was remote, and only limited financial resources were available.

In 1873, Row School Board noted that nine children of school age resided at or near Craggan Farm, by Glen Douglas road end, and that they were attending Arrochar School. This would entail a walk to school of at least five miles, and possibly more.

The substantial number of children living at just one location underlines the scale of the problems faced by those charged with delivery of the new system.

Glen Douglas had the misfortune to be located at the meeting point of three different parishes: Arrochar, Luss and Row (Rhu). This was to provide a textbook example of the weaknesses of the parish-based system, with each school board focussed on fighting its own corner.

The financing of the new school formed a bone of contention right at the outset. In the absence of a custom-built school, the only option was to form one at a farm, all existing habitations in the glen being related to agriculture.

Accommodation was found to be available at Invergroin (left), a farm situated about mid-point in the glen. As well as finding a place for a classroom, the other vital ingredient was living accommodation for the teacher.

It seems to have been only through the co-operation of the tenant farmer there that space was made available for both. He would have been renumerated.

Invergroin Farm lay in Arrochar parish, and so Arrochar School Board was now in the driving seat. With children attending from the other two parishes, Arrochar was very mindful that the other boards should be contributing to the running costs.

A formula was arrived at whereby Luss and Row would make contributions based on the proportion of children going to school from each of them. This might have seemed a good solution, but in practice numbers attending could fluctuate widely.

While some farm tenants and their employees might be stable over a period, their children could easily slip out of the prescribed age limits. In addition, quite a proportion of farm workers were hired on a year-by-year basis, the term start being either May or November. So the numbers of eligible children varied considerably over a single session.

What was termed a Combination School Board was formed over and above the existing boards in an attempt to smooth out their differences, and inter-board friction was by no means confined to Arrochar, Luss and Row.

The first known teacher was Miss M.E.Campbell, appointed by Arrochar School Board, but in a rare instance of co-operation, the Board agreed in 1881 to transfer Miss Campbell to Ardlui School, after a request from Luss to have Miss Charlotte Colquhoun appointed in her place.

By the late 1880s Miss Jemima McNaughton, one of the daughters of the postmaster at Arrochar, was schoolmistress. She commuted to the school on String Road, a rough track over wild and exposed terrain between Arrochar and Invergroin.

This was part of a route once used by the McFarlanes of Arrochar to get to and from Luss Church, before the construction of a church at Arrochar.

Miss McNaughton (on left in picture of Arrochar Post Office, right) would have got home only at weekends, and only if the weather permitted. It must have been a tough life — and the teachers at this period would have needed to be young, fit and adaptable. All the early teachers were single women.

In those formative years, the school session at Glen Douglas ran from the start of November till the end on July. Miss McNaughton was paid at the rate of £15 for half a year’s salary.

By 1889, a major difficulty arose — the farmer at Invergroin made it clear that he wanted his accommodation back. The Board told Miss McNaughton that her services would not be required beyond the following July.

Accommodation was available at Doune Farm in Luss parish. Luss School Board confirmed that the school would be conducted in what had been a milk store. But no accommodation for the teacher was to be found at the farm.

It transpired that Mr McFarlan, the tenant at Tullich Farm, also in Luss parish, was willing to provide accommodation for a school on his property over the winter months of the coming session. Presumably there was also living space for the teacher.

It was now becoming clear to all that running a school on such an ad hoc basis was simply not good enough. The boards agreed to provide a custom-built school, and asked for estimates for an iron school sufficient to house 20 scholars, with an attached room for teacher accommodation.

Messrs Braby and Co., of St Enoch’s Square, Glasgow, was contracted to erect a structure. The dimensions, including a room for the teacher, were 20 feet by 14 feet, which sounds very cramped.

In December 1890, Arrochar Board undertook to communicate to Miss McNaughton that they intended to transfer her to the new school, at an increased salary, to be agreed afterwards.

The new facility went under the grand name of Glen Douglas Public School, reflecting the fact that all the scholars, as they were then termed, would begin and end their formal education there.

The new school was located in Luss, rather than Arrochar, parish. Miss McNaughton was seen as a tried and tested candidate, but she was not long in this new post. Perhaps the very limited teacher accommodation played a part in her early resignation.

This might be reinforced by the resignation in December 1891 of her successor, Miss Clachar. The next appointee was James A.Reid, a resident of Tarbet, and he was engaged for three months at a salary of £30 per annum.

An innovation in 1892 was the introduction of a school logbook, a key source of information about the life of any school. It was limited by a strict protocol, forbidding the teacher to advance any opinions. The average attendance that year was nine boys and 3.6 girls.

A festering source of friction across the boards came to a head in 1893 — the settlement of Arrochar’s share for the cost of the school, amounting to £36.

Arrochar complained that it had not been consulted when the decision to go ahead with a new school was made, because it had no scholars attending at the time. Common sense eventually won the day, and the three boards settled their differences.

Turnover of staff continued to be rapid, however, and it was not until May 1894, with the appointment of Mrs Millar as teacher, at a salary of £50 per annum, that there was some continuity.

Her appointment coincided with a major milestone in the history of the glen, the opening of the West Highland Railway which meant there was now a direct link to outside communities.

One immediate impact on the glen population was the introduction of families connected with the maintenance of the track. They lived in custom-built cottages beside the track.

The glen’s economy had rested on those employed in agriculture, save for a few children of hut-keepers when railway construction began in 1890.

Hut-keepers, often there with their families, helped run the many construction camps that sprang up at 70 locations, one of which was Glen Douglas.

In 1894, there were 18 pupils on the school roll, several of whom were from such families. However, with the completion of the West Highland railway, they moved away.

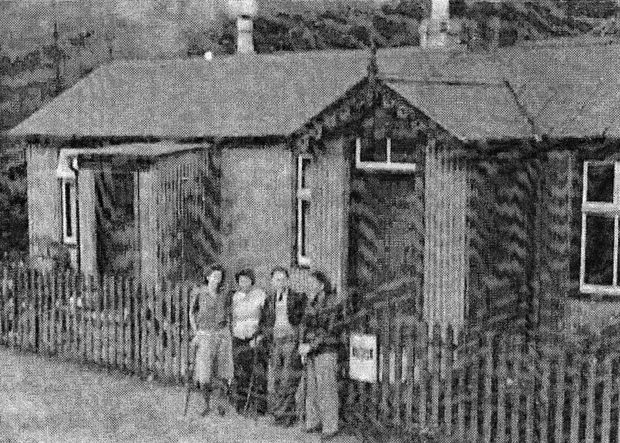

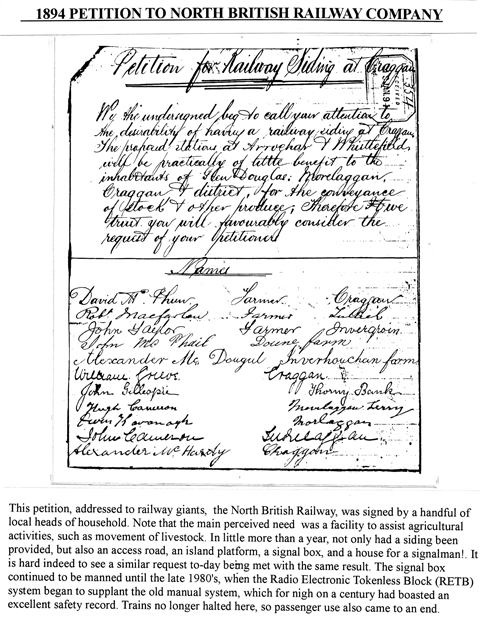

A handful of local people petitioned the mighty North British Railway Company to provide a halt and sidings at Glen Douglas, so that farmers could transport livestock all the more easily.

In a swift and decisive action unthinkable today, not only was a halt provided within the year, but an island platform, a signal box, and a house for the signalman and his family were built as well.

The only drawback was the status of the halt. It was not an official station, and apart from local trains, through passenger trains would stop only by special request — by no means straightforward in the early years.

In theory teachers could now commute to the school from nearby communities, and Mrs Millar appears to have taken advantage of this for at least part of her tenure after Luss School Board petitioned the railway company.

When the yearly examination by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate took place, the venue was Luss Public School, which was also the venue for more relaxing activities — a Christmas entertainment, and a holiday for the annual Luss Highland Games.

On the other hand, Arrochar Fast Days were being observed in the 1890s and beyond, usually the Thursday before Holy Communion. By that date, such Fast Days, once observed in every parish twice yearly, had become something of an anachronism. Rosneath had given up the practice as far back as 1875.

The catchment area of the school extended over and above the glen itself. School attendance records are available from 1897 onwards, and these reveal that children were coming from as far afield as Morlaggan to the north, and from the site of what is now Glenmallan Jetty to the south.

For these “distant children”, as they were called, just getting to and from school represented a considerable challenge.

A good example is the McGlone children, who lived at a house called Thorniebank, lying between the Glen Douglas road end and Glenmallan. They had to walk over three miles, including a steep climb of over 500 feet.

For them, and others, attendance could be quite patchy, much to the chagrin of the teachers, who set high store by the good attendance statistics.

For the next generation of McGlone children, the situation became even worse. A family move to Glenmallan meant that the walk to school now increased to well over five miles.

At the turn of the century, the Combination School Board made an approach to the Scottish Education Department to have the status of Glen Douglas School upgraded to a grant-earning school.

The response was positive, on condition that offices and a dwelling for the teacher be provided.

Luss School Board approached Messrs Spiers in early 1900 to price an addition of two rooms to the gable end of the existing schoolhouse, as teacher accommodation. This was costed at £95, and it was agreed to go ahead.

Mrs Millar tendered her resignation at that stage — maybe she did not wish to live at the school. By the start of the next session, the extension had been completed, at a cost of £152, including some agreed additional work.

The school was now adopted as grant-earning, and the services of Miss McCrae were engaged. Previously employed at the even more remote Glen Etive School, she asked that a garden and washhouse be provided.

All seemed set fair for a bright future, but in November that year she resigned. The next appointee was Alexander Robertson, a married man with a young family. His salary was set at £60 per annum.

He frequently petitioned the School Board for an increase in salary and invariably appears to have been successful.

He noted in the School Log that he found there to be no scheme of work, nor a school timetable.

A 1901 HMI said: “This small remote school is taught very faithfully and intelligently. The children read with very satisfactory fluency. They write in a bold and well-shaped hand, and spell with satisfactory correctness.

“They were frank, pleasant, and anxious to do their best, and discipline and general tone were very genial. Good progress was made in arithmetic, but singing was somewhat lacking in tone. Physical exercises were pleasantly gone through, and needlework was good.”

That year the school leaving age was raised from 13 to 14, but for most children, their schooling would still begin and end at the same school.

The Colquhoun family of Luss took a paternal interest in the school, paying the occasional visit. In 1901, Sir James Colquhoun arranged for the children to be treated to a visit to the Glasgow Exhibition of that year.

There were end of term school prizes, originally based on good attendance, but by 1903 prizes “for diligence” were being presented to all the children, a laudable practice that continued until the closure of the school.

These might have been expected to be provided by Luss School Board, but occasionally they were sponsored by the Arrochar Board. Prizes were often presented by Miss McFarlan of Tullich Farm, a former pupil and drill instructor.

In 1902 the children were given Coronation Medals, by Mr Allan, Ironmonger, Helensburgh.

In due course, one of Mr Robertson’s own children, Alexander Stewart, was added to the school roll. Two children were making good progress in Latin.

Throughout the time of Mr Robertson the Arrochar Fast Days were observed. It is believed he was an elder at Arrochar Church. For the children, this meant a half-day holiday.

A positive change in the wake of the Education (Scotland) Act of 1908 was a responsibility to institute medical and dental examinations and treatment.

School boards were required to have regard to the general well-being of pupils, such as ensuring adequate clothing and footwear. Providing school meals, however, was still a long way off, only being brought in at Glen Douglas in the late 1940s.

The life of the school was shaken in the spring of 1913, when Mr Robertson took ill. Row School Board provided a relief teacher, Miss Margaret Maughan, previously the teacher at Glen Fruin School, to allow him to undergo medical treatment. She commuted by train from Helensburgh.

Despite an operation, Mr Robertson died that September, and Miss Maughan was appointed teacher in his place. As the house was a tied one, Mrs Robertson and her family had to leave.

Arrochar Fast Days were no longer observed at the school, but otherwise school life continued as before into the onset of the First World War, during which the logbook reveals little disruption.

On Christmas Eve 1914, the children were as usual given presents from Sir Iain Colquhoun, including books, tools, dolls, toys, crackers and sweets.

A potentially serious accident occurred near the school in October 1915, when pupil Nicol Scobie (13), son of a railway worker, was injured in an explosion. Another boy had found several detonators, and when several boys were dissecting one, it went off.

Miss Maughan administered first aid and bandaged the boy, who was taken home by cart. Dr Anderson from Garelochhead attended, and the lad was removed to Helensburgh Infirmary. Several fingers had been scorched at the tips, and he suffered a deep gash to one thigh. He made a good recovery.

Investigation revealed that one boy had come across the detonators on the land of a nearby farm. The farmer conceded he had previously used detonators for blasting, but he denied ownership of the one that had exploded.

The Education (Scotland) Act 1918 saw the abolition of the 947 school boards and their replacement by 38 Education Authorities, based primarily on counties, but separate from county councils.

Also set up were area committees, with Glen Douglas School falling under the Helensburgh District School Management Committee. The number of children attending at this time was 18.

The Helensburgh and Gareloch Times often listed all those in receipt of prizes. These were still sponsored by Lady Colquhoun, and often presented by either the minister at Luss or Arrochar.

As a Christmas treat, Mr and Mrs McFarlan of Tullich Farm often entertained the children to tea and cakes, and gave them books, games, toys, and dolls.

In 1919, the new session began on September 5, after nine weeks holiday, an extra week having been added by Royal Proclamation, to mark “Victory Year”. Another annual royal holiday was Victoria Day in early May.

Older children with a farming connection would be granted absence at very busy times, such as lambing, gathering, and planting and lifting potatoes. Children in Dumbartonshire were still being granted leave to help with potato harvesting until around 1960.

Visits by doctors and dentists had been a familiar feature of school life since 1908. For many years, Helensburgh-based Dr Mildred Cathels was the Medical Inspector of School Children, and dentists at some stage began to use a portable foot-operated drill.

In a relatively remote community, the usual round of childhood illnesses were less frequent than in more crowded places, but there were periodic outbreaks of influenza, measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, and so on.

With the likes of measles and scarlet fever, the school might have to be fumigated, along with other precautions. In the case of children living among farm animals, ringworm could surface from time to time.

In 1926, the teacher and pupils were medically examined for any signs of the once-feared diptheria. Vaccination against this illness and against whooping cough began to become widespread.

A change of teacher took place in 1924, with the retirement of Miss Maughan, who had taught at Glen Douglas for 11 years and completed 35 years of teaching in Dumbartonshire. A presentation was made to her at Tullich Farm by Mr McFarlan.

Miss Thomasina Adamson was appointed as the new teacher. The roll at this time dropped to six pupils, showing how much numbers attending could fluctuate.

In addition, one family moved to Glenmallan, where a mixture of both health issues and distance from school compounded the matter of poor attendance. Fortunately for the family, a custom-built school was opened at Glenmallan in 1926.

A logbook entry for 1926 refers for the first time to a pupil sitting the qualifying exam, and passing very well. This scholar progressed to Hermitage School.

An innovation was the staging of an end of session Parents Day, when fathers and mothers were invited to inspect examples of children’s writing, drawing and craft work, and be entertained to tea and cakes. Normally only the womenfolk attended.

On June 10 1929, the pupils were invited to take part in Loch Lomondside Children’s Sports the following Saturday. This was an initiative by the Luss Highland Games committee, whose ambition was to instil a love of sports in local children.

When the new session began in August, the logbook revealed that two pupils had progressed to Hermitage School, with the roll now down to four.

That year also saw the demise of the education authorities, with education now becoming part of the remit of the county councils. However, Helensburgh District School Management Committee continued much as before.

In January 1930 the teacher acquired a portable wireless set, and the children listened to their first educational broadcast. That June, on the King’s birthday, the pupils listened to “Trooping the Colour”.

But there was still no telephone service in the glen, apart from a private one at Glen Douglas Halt, and this situation continued throughout the life of the school.

In the 1930s there were three changes of teacher. Miss Adamson resigned at the end of the 1930 session, her replacement being Miss Agnes Archibald who had family connections with Garelochhead.

In August 1930 Dr McHutchison, the county Director of Education, who visited to explain the new library system. This was the start of a twice-yearly consignment of library books for the pupils and some for adults, the school now serving as a branch of the county library service. The books were available for six months.

From this point the Director of Education paid an annual visit to the school, and for some time brought the two crates of eagerly anticipated library books. The school did have a library, courtesy of J & P Coats of Paisley.

The portable three-valve wireless must have proved less than ideal, with another wireless set installed in May 1931. It was described as working perfectly.

In June 1933, Miss Archibald resigned, as she was to marry. Her husband-to-be was Dugald Black, a shepherd employed by Graham Cooper at Craggan Farm.

The Coopers lived in the farmhouse, but with the marriage and then the start of a family by the young couple, they vacated it for them and moved to Helensburgh, where they already had a home.

Well-known in the town, they ran the Cairndhu Hotel for many years, while still managing the farm from a distance. When Dugald retired in 1957, he was presented with a prize by Sir Ivar Colquhoun for 30 years of service with the same employer.

Miss Agnes (Nan) Colquhoun took up the reins at the school, and had a brother and a sister with her at the schoolhouse. Most of the teachers, including those who were unmarried, usually had a family member there as well.

In 1934 one pupil left school to proceed to further studies, this time at the Vale of Leven Academy. That left only three pupils on the roll at Glen Douglas.

In June 1935 the children were being taken by car to the Loch Lomondside School Sports at Luss, courtesy of Mr Taylor at Tullich Farm. At Christmas, the custom continued of each child receiving gifts from Sir Iain Colquhoun’s Christmas Treat Fund.

In April 1936, Miss Colquhoun left to become headmistress at Muirlands School, and she was replaced by Annie Ross, a recently qualified teacher from the Vale of Leven, and her brother, John.

The HMI report that autumn stated: “There are five pupils, one of whom is in the senior division, as well as one junior and three infants. Attendance has been maintained at a remarkably high level.

“Accommodation and equipment are very satisfactory. The school has a good water supply. The young teacher is carrying out her duties very conscientiously.”

The school roll had two additions early in 1937, with the arrival of the six year-old Morrison girl twins. They lived in a railway cottage at Morlaggan, which meant a long and potentially dangerous journey to school.

1937 also saw events marking the Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The children received Coronation mugs. There was a Celebration Party, the school closed for a week in May as a special holiday, and later in the month there was a half-day holiday to mark the King’s birthday.

The end of that session saw four children achieving perfect attendance for the school year.

1938 brought the Glasgow Empire Exhibition, and on May 2 the school closed for a day to mark the official opening by the King. In September, the school closed for a day to enable the teacher and children to visit the exhibition.

It was a happy time, but with the onset of war in 1939 things were going to be very different. Unlike the Great War, the Second World War quickly made its mark on the workings of the school.

One of the most tangible signs was the arrival in the glen of child evacuees from built-up areas.

After closure of the school for a week in early September 1939 — by government decree — the roll was swollen by four evacuees, adding to the ten resident children. A fifth evacuee also turned up, but he was found to be too old.

Before the end of September the three Morgan children from Clydebank had returned home, and a boy from Glasgow had as well, leaving no evacuees on the roll. This outcome would appear to have been all too common.

Being uprooted from their surroundings and taken to such a different place, with no family support, must have been traumatic for many of the children.

There was at least one other evacuee at the time of the 1941 Clydeside Blitz, but his stay seems to have been short-lived. Some evacuees elsewhere, such as several at Glenmallan School, were able to arrange to stay with relatives in the countryside.

Another reminder of troubled times came with the construction of an air raid shelter across the road from the school. It was built of brick with a concrete roof.

January 1940 heralded the onset of very severe weather, with deep snow drifts, and it was not until mid-February that normal school life resumed.

This was far from uncommon — the setting of Glen Douglas meant that there were many more extremes of weather than at places nearer sea level. Snow and ice could linger far longer, and wind and rain were all the more ferocious. The winters of 1895, 1947 and 1963 were especially severe.

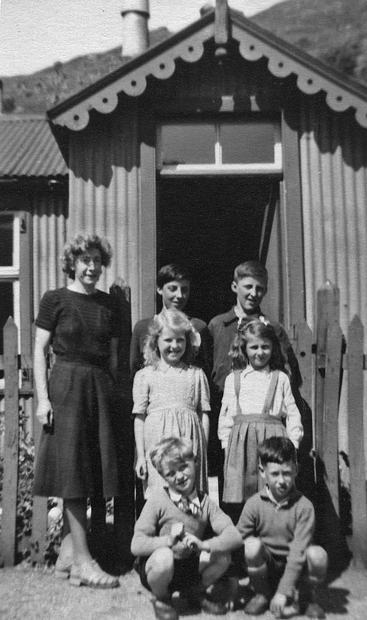

A school photo from 1942 (left) shows four very blond children, almost certainly from the family of Bob and Helen Scott, who shared signalbox duties at Glen Douglas halt from the 1930s until 1956. The centre boy in the back row is thought to be Billy Scott, whose own children were attending the school when it closed in 1965.

The end of the war brought major social change. The much-delayed raising of the school leaving age to 15 years finally took place, and with it the progression of pupils from one school to another.

Like other similarly placed schools, the designation of Glen Douglas now changed from public school to primary school.

A new challenge now reared its head. Since all children were now expected to attend a secondary school on reaching the requisite age, this meant attendance at Hermitage School in Helensburgh.

For most children in the glen, the only practicable way of doing so on a daily basis was by means of the local train service. Children needed to be at Glen Douglas Halt for 7.30am.

Margaret McNiven recalled travelling daily with younger sister Jessie from the late 1940s onwards. They lived at High Craggan, which meant a walk of a mile to catch the train.

“We’d be in Helensburgh about 8am,” she said. “When we got to the school, there was nowhere to go, and we just had to hang around until classes began.”

For pupils living further away from the railway, it was even worse. When George Shaw attended Hermitage in the early 1950s, he faced a walk of over three miles to catch the train. This meant getting up very early.

George’s plight came to the attention of the Sunday Post, and a major article highlighted his case. The Shaw family moved away from the glen soon after, and attendance at school may well have a factor in this decision.

Despite the age cut-off now in place, the school roll had swollen by 1947 to 12 pupils, and Helensburgh District School Management Committee reported to the County Council that the classroom was too small.

By early 1949, the County Council was drawing up plans for a replacement school. However, as had happened before, the situation changed very rapidly. At the start of the new session, the roll had shrunk to a single child.

By December the arrival of a new family meant four more children attending, and before long, several more pupils appeared.

A highlight of the following year was a visit by teacher and pupils to the official opening of the ground-breaking Loch Sloy Hydro-Electric Scheme on October 18 1950 in incessant heavy rain.

One pupil who attended remembered not only the rain, but also the mud, the expectant crowds, and what seemed like endless waiting. At last the Royal cavalcade swept through, and it all seemed over in an instant. Even so, it was a truly historic moment.

The 1950 picture (right) shows pupils with Miss Annie Ross, left to right from back row: Ian McDonald, Robert McDonald, Christine Cuthertson, Nancy McDonald, Angus Cuthbertson, Alistair McIntyre.

Time-honoured treats for the children continued into the 1950s, such as attendance at the Luss Christmas parties. By that time, car ownership was becoming more common and the goodwill of Sid, the warden at Inverbeg Youth Hostel, and of one or two of the local farmers, was called upon as the need arose.

Most cars of the day were, however, unable to surmount the very steep ascent of the road above Inverbeg, certainly not with a full load of children on board, so it was a case of getting out and walking up to where the gradient eased back — another cherished part of the whole adventure!.

Miss Ross relinquished her post at the end of session 1952 to become headmistress at Luss.

When the new session began in August, no replacement teacher was in post, so the children were taken by taxi to Arrochar Primary School, an arrangement that continued till the end of the year. In harsh winter weather, the taxi was frequently unable to reach the glen because of ice and snow.

It was not until the start of 1953 that a new teacher, Mrs Elizabeth Woods, was ready to start.

The local press reported that only two out of four candidates had been deemed suitable, and it emerged that there had been “lively debate” within the Education Committee as to whether fifty was too old.

This was not due not to any inability to teach at that age, rather because of the living conditions. But Mrs Woods settled in quickly, supported by her husband, a retired army officer.

She soon became very popular with the local children and their families. However, she began to experience serious health problems, and it was found necessary to take the children to Arrochar School on several occasions.

Despite medical treatment, Mrs Woods passed away within eighteen months of her appointment.

There was prolonged delay in appointing another teacher, and for the whole of 1954-55 the children were taken by taxi to Arrochar School. Once more, bad weather meant weeks of absence.

The local community began to have serious doubt as to whether the school would ever re-open, and they brought their anxieties to the attention of the education authority. But by the summer of 1955, another teacher was appointed.

When the new session started that August, Mrs Kate Melrose was able to welcome back the half dozen pupils. As with Mrs Woods, she had her husband there to offer the support needed to run both school and home.

She resigned her post at the start of 1960, and they set up home in Lanarkshire. A new teacher, Miss Marjorie Fraser, was appointed, and she was supported by her sister.

Not very long afterwards, however, the even tenor of life in the glen was given a serious shock.

From 1955, surveyors had been active in the northern half of Glen Douglas, measuring and mapping the terrain. There was talk of a “hush-hush” government scheme, but there were few facts.

By 1962, civil engineering contractors, headed by John Howard of London, had begun to transform the landscape on a mammoth scale. Initially a NATO facility, this would eventually become RNAD Glen Douglas.

The project was to provide storage facilities for a huge underground ammunition store. Carried out under the auspices of the Admiralty, a private road was constructed to Glenmallan, where a large jetty was also built.

Many suspected that nuclear weapons were being stored in the glen, and a number of CND marches targeted the installation. But after a question in Parliament, it was stated that no nuclear weapons were being kept there.

For the school this led to significant changes. Five homes at the western end of the glen were demolished, as they were too close to the military installations. One, Tullich Farm, was relocated further down the glen.

The MOD built several terraced housing blocks, comprising 16 households, to accommodate employees. But the Admiralty stated that the school could not continue at its existing location.

Discussions began with the County Council over the possible relocation of the school further down the glen. But the talks came to nothing, and the school closed its doors for good in 1965.

There were 14 children on the roll, of whom eight were from MOD families. Several of the children were from the household of Billy Scott, a married shepherd and past pupil. His parents, Bob and Helen Scott, shared signalling duties at Glen Douglas Halt.

Now the glen children once more found themselves being taken to Arrochar School. Miss Fraser, now retired, and her sister, were permitted to continue living at the schoolhouse until it was demolished in 1970, when they were relocated to Garelochhead. She died in 1974, and it was truly the end of an era.

In its day, the school played a vital part in the life and soul of the community. As well as housing a branch of the county library, church services, for both children and adults, were conducted by the minister from Luss in the summer months. The school also served as a community centre, with social gatherings from time to time.

Today, paradoxically, while there may very well be more people working in Glen Douglas than at any time in the past, the resident population is tiny.

Doune Farm is the only working farm left. The houses built for railway employees have long gone, and even the MOD houses were demolished before the Millennium.

A school photo, probably from late summer 1950 shows Miss Agnes (Nan) Colquhoun, with Jackie the postman.