IT SEEMS strange to link those legendary figures from the Crusades, the Knights Templar, with Millig and what is now Helensburgh — but there is a connection.

The same can be said of both Rhu and Glen Fruin, local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre has discovered.

The story of the Crusades has long gripped interest, and a vital part is the role played by the so-called Military Orders, the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller.

Their original function was the protection and welfare of pilgrims making the hazardous journey to the Holy Land, after the Crusader conquests.

In recent years, the profile of the Knights Templar, and their alleged associations with Scotland, was further raised by Dan Brown’s best-selling novel, “The Da Vinci Code”.

In recent years, the profile of the Knights Templar, and their alleged associations with Scotland, was further raised by Dan Brown’s best-selling novel, “The Da Vinci Code”.

The Knights Templar, originally known as the Order of the Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, were founded in 1119.

Essentially warrior monks, the personal lives of the Templars were austere, but their skills in commerce and banking, as well as in warfare, helped them to become extremely wealthy.

A truly cosmopolitan body, their arrival in Scotland has been dated to 1128, during the reign of King David 1st, who is said by English Cistercian monk and writer Ailred of Rievaulx to have kept himself surrounded by Templars.

They had two main bases in Scotland, one at Balantrodoch — now Temple — in Midlothian), and the other at Maryculter in Aberdeenshire. Over 600 other properties all over Scotland were gifted to them by important people.

The first person to bring the name Temple Lands of Millig to public notice was John Guthrie Smith (1834-94), an author and antiquarian (right).

In his book “Strathendrick and its Inhabitants from Early Times”, published posthumously in 1896, he recorded that “Robert Galbraith of Culcreoch, and James Galbraith, younger, were vested in the Temple Lands of Millig, purchased from George Cunningham of Hag, 22 June 1608.”

Smith’s wife, Anne Penelope Campbell Dennistoun, was a Dennistoun of Colgrain, whose associations with that place go back to the 14th century, and his source for this was the Dennistoun Manuscripts.

An interesting character in his own right, Smith built a grand mansion in the Scots Baronial style next to the historic Mugdock Castle, and he died there in 1894.

Corroboration that Temple Lands of Millig were on the site of what is now Helensburgh can be obtained from another source, the study “The Knights of St John of Jerusalem in Scotland”, co-edited by Drs Cowan, Mackay and Macquarrie (1983).

Their work includes a listing of known Templar and Hospitaller properties, arranged by county, and under Dumbartonshire, appears the place-name Millig.

The name does not feature anywhere else in the county, and the authors provide several variants in the spelling that they encountered — Moyles, Mulligs and Mullyis.

Other temple names occur in the district. The place-name, Temple of Row (Rhu) appears in a land deed of 1674: “John Smith, indweller at Temple of Row, was witness to a sasine of land called the ferry-land, in the office of the ferry-boat of Connell, in the lands of Ardinconnell, parish of Row.”

Another instance is Temple of Inverlaurin in Glen Fruin, quoted in a land-deed of 1625. One of the variants of this name given by the St John authors is “Hynunlaneran”, from a rental deed of 1539-40.

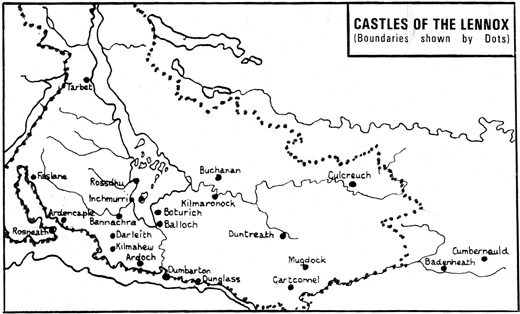

Within what was known as the earldom of Lennox, which encompassed the historic Dumbartonshire and an extensive tract of land in west Stirlingshire, there were a multitude of temple place-names.

Many properties in the Lennox came to bear the place-name “spittal”, which usually signifies a link with the Knights Hospitaller.

As to the mechanism through which the Military Orders came into possession of these places, John Guthrie Smith was in no doubt that all of them stemmed from gifts by the earls of Lennox.

Peter McNiven, a leading place-names authority of the present day, considers that they were most likely endowments by either the earls of Lennox or the bishops of Glasgow.

There is a chronic lack of information about the Templars in Scotland — they kept almost no records, and many of the Knights were illiterate.

Robert Ferguson, author of the 2010 book “The Knights Templar and Scotland”, provided estimates of their numbers here. He reckons the number of Templar Knights at any one time was never more than four or five.

But there were a number of other Templars present, including a handful of chaplains, and between twenty and thirty sergeants, men who had taken Templar vows but who were lower in the hierarchy.

Among other duties, the sergeants were responsible for managing the various properties, basically as estate factors. According to Ferguson, Templar income in Scotland was generated primarily through agriculture and fishing.

Those carrying out these pursuits would have been non-Templar tenants, most likely local people. It is likely that those working the Temple Lands of Millig were engaged not only in farming, but in fishing too. Perhaps they operated a mill.

Each county had a bailli, a sergeant who collected the rents and helped settle minor disputes.

Because of the small numbers of Templars in the country, it seems likely that those employed at places like the Temple Lands of Millig, would have had only periodical contacts with their employers, probably the bailli, or other Templar sergeants.

Templar tenants enjoyed many benefits. Their landlord, effectively an absentee, had none of the capriciousness of some conventional lairds.

Their families were free to follow whatever occupation they wished; they were exempt from other taxes; and they were not required to sit on juries.

The net Templar income derived from Scotland amounted to some 300 marks — about £200 — at the end of the 12th century, and by the end of the following century the amount had tripled. The money raised was transmitted to Palestine.

The Templars were always considered much more prosperous than the Hospitallers. But this prosperity was to contribute to their downfall.

In 1307 King Philip 4th of France ordered the arrest of the Templars in what is thought to be an asset-grabbing exercise. The King desperately needed money to finance his political ambitions, and the vast wealth of the Templars was too much of a temptation.

The main charges they faced centred on heresy, and the tortures used to extract confessions, and the subsequent executions, were savage. Philip also used his own and papal authority to seek similar action beyond his own kingdom.

In England, the Templars were arrested only after nagging by the Pope. In Scotland, the situation was complicated by the Wars of Independence, started in 1296.

When arrests were eventually made in Scotland in 1309, two of the four Templar Knights known to have been in the country at that time, fled.

The other two were arrested and interrogated, but no decision was reached, possibly because of the delicate political situation at the time. All known Templar Knights serving in Scotland were English-born, and the interrogators were also English.

The final blow came in 1312, when the Pope suppressed the Templars. Again, there were charges of heresy, some of which were ludicrous. Templar properties were confiscated and made over to the Knights Hospitaller.

The Templars were their perhaps own worst enemy. The St John book states: “Whatever good qualities they may have had, the Templars never endeared themselves to many of their neighbours, in Scotland and elsewhere, and in some cases, the dislike, which ultimately was to contribute to their downfall, appears to have been amply justified.”

Robert Ferguson wrote: “As the Templars’ wealth increased, their early ideals faded away, and were replaced by arrogance, cruelty and greed. It appears that it was this image that ultimately caused the Order to be brought to an end.”

Much of the impressive infrastructure created in Scotland by the Templars continued to function for centuries afterwards. Guthrie Smith noted the holding of a full Temple Court near Buchanan as late as 1461, although in the presence of a Knight Hospitaller rather than a Templar.

There are tales – but no proof — of buried Templar treasure, suggestions that some Templars fled to Scotland, and even a long-standing belief that Knights Templar assisted Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn.

The other so-called Military Order, the Knights Hospitaller was known originally as the Order of Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem. Their original emphasis was on the support of sick and injured pilgrims visiting the Holy Land.

They were always considered the poor relations of the Knights Templar, until the suppression of the Templars in 1312.

But in time they came to boast some impressive possessions, such as the mighty Crusader fortress known as Krak des Chevaliers, in present day Syria.

If little is known about the Templars in Scotland, less has come to light about the Hospitallers. For instance, the date of their arrival is unknown.

However, the way they operated here is thought to have been along similar lines to the Templars, and lands and buildings were gifted to them, although on a humbler scale than the Knights Templar.

Their main Scottish base was at the Preceptory in Torphichen, in what is now West Lothian.

As with the Templars, the Knights Hospitaller in Scotland effectively were an extension of the Priory in England, and like them, their primary allegiance was to the English crown.

It might be supposed that the Scottish Wars of Independence would have made their presence in Scotland untenable.

The 1983 study “The Knights of St John of Jerusalem in Scotland” concluded that they did leave the country for a time, yet, as they also point out, within six months of the Battle of Bannockburn, King Robert was issuing a charter confirming to the Hospitallers all their lands, rentals, churches and other possessions.

With the suppression of the Knights Templar and the handover of their former possessions to the Hospitallers, many temple place-names came to be supplanted by ‘spittal’ equivalents.

One good example of this switch comes in a land-deed of 1664, when sasine took place of “the Temple Lands, extending to the one merk land called the Spittal of Thombouy” (now Dumbuck).

Add to this the lands gifted directly to the Hospitallers, that is how there came to be many more spittal than temple place-names. But a limited number of temple place-names did survive.

Spittal names in the area include: Spittal of Auchentullich (1652); Spittal of Colgrain (1619); Spittal of Darleith (1674); Spittle of Dumfine (1774); Spitle of Inverarnan (1745); Spittal of Kilbride (1747); Spittal of Rahane (1519); Spittal (near Strone of Luss) (1505); Hospitals of Cambrone (Cameron) and Stuckrodger (both near Balloch) (1387).

Another possible example is Spittellands de McKinno. This may be synonymous with what was later known as McKenzie’s Acre, thought to be near the Chapel of Glen Fruin.

The St John study lists “Tarbert” (Dumbartonshire) in its county compilation, which however lists together temple and spittal lands.

This number is impressive, but there is an even greater concentration in some other parts of the Lennox. John Guthrie Smith unearthed eleven spittal names in the parish of Drymen alone.

Any discussion of possessions of the Knights Hospitaller has to take on board the confusion that can arise from their very name.

The root words “hospes” and “hospitalis” carry an original sense of “guest”, so derivatives like “hospital” and the more usual “spittal” could in theory apply not only to properties owned by the Knights Hospitaller.

It could also apply to places like inns and shelters, and even to hospitals — in the modern sense of the word — with or without any Hospitaller connection.

An in-depth study of mediaeval hospitals in Scotland by Derek Hall, from both field work and scrutiny of records, was published in 2006 and provides a great deal of useful information.

Hall lists 178 hospitals, of which 23 are named spittal. In this district, only Geilston is listed, but its use remains unknown.

Spreading the net a little wider, nothing local appears under Hall’s sub-heading of Almshouses; there is one under Bedehouses (Dumbarton); one under Hostels for Travellers and Pilgrims (Kilpatrick); nothing under Hospitals for the Care of the Sick; nothing under Poorhouses; and one under Leper Hospitals (Dumbarton).

An almshouse is said to have been provided by John McFarlane, 15th Clan Chief, built “for the reception of poor passengers who might happen to require shelter in visiting or passing through the district”.

This lay on the mainland shore opposite McFarlane’s stronghold on Eilean a’ Vow, Loch Lomond, at a place called Bruitford. However, John was Clan Chief from 1612-1624, much later than the mediaeval period.

These findings suggest that virtually all locally occurring hospital and spittal place-names refer simply to properties belonging to the Knights Hospitaller. Whether any served as inns for travellers or pilgrims is speculation, but in a few instances, the locations make it likely.

For example, the Hospitals of Stuckroger and Cameron — often named spittals in old records — would have been well-placed for anyone seeking to cross the River Leven at Balloch.

Similarly, the Spittal of Batturich (Boturich), conveniently on the east side of the loch, could have played a similar role.

Another candidate might be Spitle of Inverarnan, at the northernmost boundary of the Lennox, ideally placed to provide accommodation not only for travellers in Glen Falloch.

Peter McNiven, a leading place-names authority of the present day, has suggested that the disposition of certain spittal place-names in the Lennox and in the earldom of Menteith could suggest a route used by pilgrims or those attending markets.

One factor that might go against the suggestion of spittals as purely inns stems from the situation in the county of Argyll.

According to Robert Ferguson, author of the 2010 book “The Knights Templar and Scotland”, this was about the only region in Scotland without a Templar presence. It would appear that the Hospitallers also had no possessions there.

Temple and spittal place-names appear conspicuously absent in Argyll where, if the term sometimes denoted nothing more than an inn, spittals might have been expected to feature prominently because of challenging river, loch and hill crossings.

This absence in Argyll supports the view that almost every spittal name in the Lennox does equate to a Hospitaller property.

It has been suggested that the name spittal could arise from a landowner or tenant of that surname. It is possible, but the other way round is more likely. Farmers are, or were, generally known by the name of their farm.

A local example is Coll James McFarlane, a farmer at Arrochar for a good part of the 20th century, who was commonly referred to as “Old Stronafyne”.

The St John book stated: “The overall distribution of Hospitaller and Templar properties follows what is known of Anglo-Norman colonisation so closely as to suggest that one quality shared by crown and settlers was an appreciation of the work of the crusading orders.

“The extent of that generosity can be seen not only in the very considerable number of properties which came into the possession of the two Orders, but also the pattern of their distribution and the high density of holdings in areas such as Fife (80); Angus (67); Annandale and Dumfries (73) and Ayr and Carrick (99).”

If the Templar and Hospitaller properties in the Lennox resulted from gifts by the earls of Lennox, it provides an insight into the origins of the earls, especially with regard to a possible Anglo-Norman connection.

Over the years, there has been a great deal of debate about where they came from.

But contemporary scholar Matthew Hammond states that King William the Lion granted the Lennox to his younger brother, David, in 1174, and that it is first referred to as an earldom in a charter of 1178. Both were sons of Ada de Warenne, who was of Anglo-Norman nobility.

It is possible that it was David who began making gifts to the Military Orders before he relinquished the earldom of Lennox in 1185, on being made 4th Earl of Huntingdon.

Another finding from the St John study is that many of the Templar and Hospitaller properties were relatively small.

While acknowledging the existence of larger properties, they suggest that many might have arisen from something akin to the practice of tithing, giving a tenth to God and His church.

They refer to “hundreds of tiny crofts and templelands dotted across Scotland from the Solway to the Pentland Firth”.

Quoting as examples the hospitals at Cameron and Stuckroger, they comment that “the Knights of St John seem to have been entrusted with the administration of these small spittals — possibly little more than bothies — in the Lennox.”

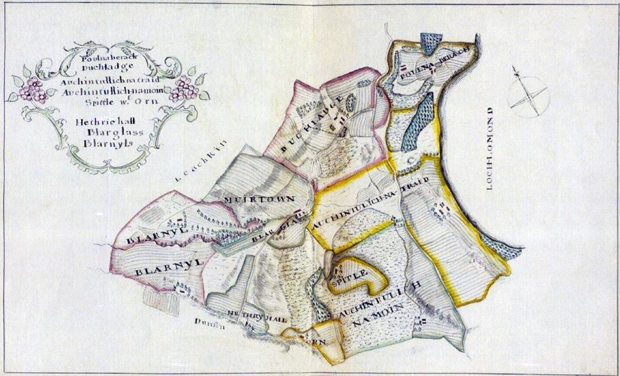

Charles Ross of Greenlaw drew up maps of landholdings for Sir James Colquhoun of Luss in 1776. One (above) depicts a spittal seemingly within the lands comprising the farm of Auchentullich na Moine, by Loch Lomondside.

The spittal, which includes a building, is dwarfed by the farm, being around a sixth of the extent of the surrounding property. Another map depicts a spittal not far from what is now the Crosskeys as no more than a croft.

Despite the imposing name “Temple Lands of Millig”, the chances must be that it too was relatively modest.

The demise of the property holdings of the Military Orders might have coincided with the Reformation of 1560, but the foundations of a move towards lay ownership had been laid some years earlier.

While charters by King James IV of Scotland between 1448 and 1488 acknowledged grants formerly made to the Templars, the Scottish parliament of King James V was in 1528 authorising “religious corporations” to sell their land to “substantial men” who could improve them.

The end finally came in 1563, when James Sandelands, the Master of the Order of St John in Scotland, relinquished the estates, houses and lands of the Hospitallers and Templars to Mary, Queen of Scots.