WHEN compulsory education for primary age children began in 1872, it posed a challenge for hamlets some distance from towns and villages, such as Glenmallan on Loch Longside.

The educational body set up to administer the system, the School Board of the Parish of Row, did however come up with a plan to build a school there as early as 1873.

It was noted that Mr Caird and Mr White, proprietors of the mansion houses of Finnart and Arddarroch respectively, had between them twelve children of school age, 5-13, among their staff.

There were also five children living at Strone at Glenmallan, as well as nine at Craggan, at the Glen Douglas road end, along with eleven at Portincaple.

Sadly, though, the ratepayers did not deem the expense of a school justifiable.

The main option for children at Glenmallan was to make their way to Garelochhead School — and a logbook entry for that school records that twins aged five, with their older siblings, faced a five-mile walk to school. Any children living further away would surely have found this journey beyond them.

By 1905, several children of the McGlone family living at a cottage called Thorniebank, about two miles north of Glenmallan, were attending Glen Douglas School.

That entailed a walk of more than three miles and a climb of 500 feet, a tough call for a young child, especially in bad weather.

By 1924, the next generation of McGlone children were facing the same daily journey, initially from Thorniebank, but a family move to Glenmallan in 1926 saw them face a daily commute of five miles there and back.

Not surprisingly, school records show that there were frequent absences. But that situation was about to change.

In the summer of 1926, a school came into being at Glenmallan. It did not operate from custom-built premises, but from one of the cottages.

Elizabeth Wiltshire, a qualified teacher, was appointed, with accommodation provided for her at five shillings a week. Almost certainly, she was a daughter of Albert Wiltshire, the stationmaster at Garelochhead. Another daughter, Grace, was a well-known teacher.

Glenmallan School was classified as a ‘side school’. That meant it came under a larger school, in this case Garelochhead.

The headmaster, Thomas Neilson, cycled to Glenmallan on the opening day, but as it happened, attendance was low, owing to illness and bad weather.

For a number of years, he visited once a week to check on progress, and an HMI report in 1927 praised the good work being done at the new school.

The arrangements for teacher accommodation did not work well, and the subject came up at a meeting of Helensburgh District School Management Committee in 1928.

The chairman approached the Education Authority about the problem, but he was informed there was no lack of teachers, and accommodation could be had at Whistlefield and Garelochhead.

The school was seen as purely temporary. It was also pointed out that a local lady was running it, and if they had to recruit from further afield, there would be no difficulty in getting a teacher.

The chairman suggested that when a new school was built, it should be recommended that teacher accommodation be provided. This was agreed.

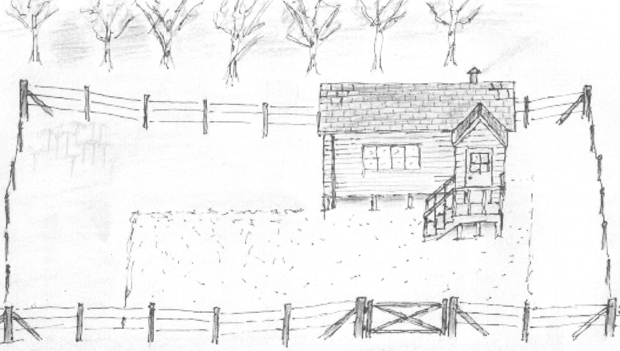

A custom-built school opened its doors in 1929. It was a small, single room wooden building, built on sloping ground,with the frontage was on a stilt-like framework. There were ten pupils.

That same year, Miss Wiltshire left for a teaching post at Rhu, and Miss Agnes Blake was appointed in her place.

This coincided with a major change in administration. Education had been a function of Education Authorities since 1918, but responsibility was now vested in city and county councils.

Glenmallan and other local schools now came under Dumbarton County Council Education, an arrangement that lasted through the rest of the life of the school and beyond.

When HM Inspectors visited the school in 1931, there were 13 pupils, and their report was again favourable: “Save for a recent fall due to influenza, attendance has maintained a good level during the current session.

“The premises, which are of a temporary nature, provide adequate accommodation with good light. Heating is effected by a stove of a type which does not conform to the Building Regulations — a thermometer should be supplied to enable the teacher to regulate the temperature, which on the day of the inspection was too high.

“The pupils are instructed by a young probationer who gives much promise and is already achieving creditable results. In the basic subjects, good progress is secured by methodical teaching on modern lines, and special mention may be made of the standards aimed at and attained in music and repetition of poetry.”

This was the era of the Great Depression, and all communities struggled through difficult economic conditions.

Former Finnart resident and pupil Winnie Bolton recalled how tough it was, but said that at the same time people could be resourceful.

“It was a hard life,” she said. “We were all poor, but we didn’t know the difference as we were all in the same boat.

“The local landlords forbade the taking of rabbits and other game from their lands. But Johnny McGlone always managed to poach something for his pot, and often shared with us — he would stop by our cottage and check if anything was needed.

“Between that, and the various kinds of fish to be taken from the loch, the mussels and clabydoos to be gathered from the shore, and our home-grown vegetables, we nearly always fared well for food.

“What we did lack was milk and dairy products, and for that I am suffering today from osteoporosis.”

John McGlone, the local roadman, who lived with his family at Strone Old Tollhouse, helped at the school. There was a stove fuelled by coal, and he filled scuttles, and probably emptied the ashes and re-set the fire.

There was also the delicate matter of emptying the dry closet, which was discreetly located behind the coal shed, and burying the contents. More than likely, that was another task that would have fallen to him, paid or unpaid.

In 1933, Annie Turner, later Mrs Walker, was appointed teacher. An honours graduate of Glasgow University, she commented in later life of the difficulties in obtaining a suitable teaching post, such was the prejudice that then existed against female teachers, even well qualified ones.

The only teaching post available to her was at Glenmallan.

A chronic problem, and one that was to persist through the lifespan of the school, was the lack of teacher accommodation. The post was however a foot in the door, and Annie was able to move from Glenmallan to Glen Fruin, and eventually gain a post in secondary education.

Annie’s early career was typical — Glenmallan saw a succession of young unmarried female teachers at the school for a limited period, before they moved on or left to get married. At that time, any female teacher who married had to quit teaching, although that would later change.

Glen Douglas School also suffered initially from a lack of suitable teacher accommodation. A turnover of young unmarried female teachers was again the order of the day.

The school was conducted from different farms, until a custom-built school was provided in 1890. The lack of teacher accommodation continued until 1900, when an annexe was added. Immediately after, a married male teacher was appointed.

Glenmallan School never had such dedicated teacher accommodation provided, and so staff continued to make their way to Glenmallan as best they could, usually from Helensburgh — a major challenge in its own right.

What is remarkable is that the school always performed to a high level, while it is clear from testimonials of former pupils that there was enormous respect and affection for the teachers, and for the school in general.

With harsh economic conditions continuing to bite, the roll had shrunk to three pupils by the time Annie Turner took up her post. Retrenchment was also taking place at Garelochhead, where the staffing complement was reduced.

In 1932, Thomas Neilson was informed that because of the cutbacks, he would have to reduce his visits to Glenmallan from a weekly to a monthly basis. This was brought about, despite his protests.

He faithfully continued his supervision, still travelling by bicycle. As well as his visits, the County Director of Education made an annual trip, while medical and dental visits also took place.

In 1938, Thomas Neilson was told that Glenmallan would no longer form part of his responsibility, but would thereafter function as a separate school, probably as part of a wider rationalisation of educational provision.

Soon after, the dark clouds of World War Two descended. For the school however, life continued, and thanks to the national scheme of evacuating children from urban areas to the countryside, Glenmallan saw an increased roll.

There may be a perception that evacuees had little or no say in their destinations, but this would seem to have been far from the case, at least in some instances. The key seems to have been the presence of family in the countryside.

It is known that a number of evacuees who lacked such contacts, and who were sent to places like Arrochar and Glen Douglas, often left for home after a relatively short period.

A big factor in the Glenmallan area during the war years was the building of oil jetties, storage tanks and a pipeline along the road at Finnart, while the Admiralty Range at Arrochar was much used to test torpedoes and depth charges.

The school had an Anderson shelter provided, with practice drills to rehearse for an aerial attack. The picture on the right is from 1939.

The post war era saw major changes in society, and this was reflected at Glenmallan School. It closed its doors around 1947-48, as educational provision was overhauled.

Glen Fruin and several other small schools also came to an end at this time, and children were taken by bus to bigger schools.

Glenmallan pupils were transported to Arrochar School. In due course, a bus was also laid on to take secondary pupils to Helensburgh.

The school building was demolished, and in the grounds was built a new roadman’s cottage in 1953-54. The McGlone family moved in from their former home at the Old Tollhouse.

Reminiscences of former pupils really brings alive what it was like to attend Glenmallan School, especially during the dangerous but exciting times of 1939-1945.

Jessie Nickel

American-born Jessie (maiden name Ronald) lived at Stronmallan, a sizeable house, and her people were reckoned to be relatively prosperous.

In due course Jessie (left), using the name Glenda Mallon, became a singer who worked with top stars including Maria Callas, Joan Sutherland, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope.

“I popped over the hedge to the school when I was three, or so they tell me. At that time I was with Graham McGlone, a big bully, as he was the oldest. Then there was Rae Bolton who lived at Finnart and Peter McKichan who walked all the way from Portincaple.

"Then the Anton girls, Norma and Sheila, with whom I am in weekly contact. My father, an American, died when I was very young, so my life was in Scotland.

At the school, I made lots of friends with evacuees. To begin with, the school had about four pupils, increasing to about seven or eight.

"Our first teacher was Miss Ferguson, who travelled every day by the slow Garelochhead bus, then cycled to Glenmallan — long way! But they wouldn't do that nowadays. Then we had Miss Hattle. She too came from Helensburgh, and travelled in the same way. We kept in touch with both until they died.”

Winnie Bolton

Winnie was born in 1924. The family lived for a time in the tiny round lodge house at the foot of Finnart Hill, before moving to another house in the grounds of Finnart House.

However, with the arrival of contractors working to build oil jetties on behalf of the American Navy, the family had to flit once more, this time to Roadside Cottage, about a mile south of Glenmallan.

They already had family at Finnart (her grandfather, James Rae, was head gardener at Finnart), but Winnie's father, James, who hailed from the North East of England, worked at the Torpedo Range at Arrochar.

He travelled there by motor bike, but in times of bad weather, he often had to stay at Arrochar during the week. Winnie's brother Rae, six years younger, also attended the school in due course.

When Winnie reached secondary school, she walked to Whistlefield Station, took the local train to Helensburgh and walked down to Hermitage School, and “got many good soakings” in the process.

She went on to study at Glasgow University for two years, but as it was wartime, she volunteered for the British Red Cross as a nurse. Shortly after, she was attached to the Royal Navy, and served in various naval hospitals for four years.

She later moved to the United States, and married an American.

“I walked a mile each way daily to school, which I attended until age 11. The McGlone children also attended — Graham was a sweet little boy.

“Owing to the sloping ground, the school was on stilts at the front, and there were several steps leading to the door. Inside, there was a very small hall, with nails to hang coats on, and buckets of coal. There was a coal stove for heating, known as a Tortoise Stove.

“I have a vague recollection that there may have been some sort of transportation from Portincaple, as Norma and Sheila Anton attended the school. Their father was an artist, and they stayed at the first house on the left on the Portincaple road.”

From her description, this sounds like the house then called Crimea, the home of James Kay, the artist.

Jean Stone

Jean was a cousin of Winnie Bolton. She and her younger sister Christine were brought by their parents, Robert and Dorothy Stone from their home at Wembley at the beginning of the war to stay with their grandparents at Finnart.

Jean joined Glenmallan School in 1939, aged 7 years. She now lives in Appin.

“The one classroom school accommodated all the pupils aged 5-12. An exception would have been Graham McGlone, who although over 12, was allowed to attend, travelling to Hermitage School once a week.

“The highest number of pupils was 13. I had three teachers, every one a winner. They were excellent teachers, and very kind.

“The first teacher was Miss Ferguson, who left not long after to get married. She would read to us on a Friday afternoon, and present us with lollipops at the end of the day.

“Fellow pupils at this time included Rae Bolton, Graham McGlone, Herbert Gray, Alan Brough, Agnes Kirkwood, Norma Anton, Sheila Anton, Peter McKichan, Jessie Ronald, Joyce Russell, Maybeth Stevenson, and Ernest?

“Our next teacher was Miss Hattle. She came from Helensburgh, where her brother had a jeweller's shop on the seafront. She travelled by moped.

“There was one awkward moment. The milkman, delivering milk for the children, on one occasion had had too much to drink, probably after attending a Burns' supper.

“He sang to the teacher ‘My love is like a red red rose’. We were all sitting round the stove, it being a cold January day, and witnessed her embarrassment.

“Once a year, we had a visit from the school inspector to check on our progress. We had to recite and sing, as well as show our exercise books.

“Our singing didn't impress, and on his next visit, he brought along a wind-up gramophone, and a recording of ‘Nymphs and Shepherds’, sung by Manchester Children's Choir — most impressive!

“It was the inspector who was instrumental in having Miss Hattle dismissed. Because she was marrying a Catholic, she would be deemed unsuitable for teaching young children.

“Miss Hattle's husband-to-be worked at the Sunderland Flying Boat Base at Rhu during the War, and later worked on aircraft down in Luton. At this time, any female teacher who married had to leave her post.

“The third teacher was Miss Horne, who travelled down from Arrochar on bicycle. Once again, she was an excellent teacher. My abiding memory is of travelling with her to Glasgow by train to attend the ballet . . . a great thrill!

“During the war, an Anderson Shelter was built near the school. We had drills, and were told what to do if there was an air raid. Graham McGlone, who was the tallest pupil, was elected to be in charge of getting rid of any incendiary bomb, using a long-handled shovel.

“For practice, he would use a ball of rolled-up newspaper, scooping it up, and throwing it over the sea-wall. Needless to say, he never had to do it for real.

“Our cleaning lady was annoyed at finding plasticine stuck to the floor, and threw away the maps we had made using it. These were recovered, over the sea-wall, on the shore.

“The school had a visit once a year from a dentist, who arrived by car. All the equipment had to be carried into the classroom, with the pupils helping.

“Anyone who hadn't had their teeth checked by a dentist over the past year had to have them examined, and fillings done as necessary. The drill was operated by foot, as there was no electricity in the building.

“A wooden box, filled with library books, was delivered monthly. There was always great excitement when the box was opened, as there were books for adults as well as children. Miss Hattle and her pupils are pictured in this 1940 image (right).

“For transport, we mostly walked or cycled to school. When my sister started school at five years of age, she sat on the carrier of my bike. It was a mixed blessing, but at least I was helped when pushing the bike up Finnart hill.

“We were living at Portincaple by this time, and were told not to cycle down the hill. Having seen several people come to grief outside Finnart Lodge, we were never tempted to do so.

“Sometimes, on a Monday, we were fortunate to get a lift part of the way on a Co-op van. This was a real treat, though we worried if we would get up Finnart hill. The engine struggled, getting hotter and hotter under our feet, but we made it!

“Fortnightly, we would get a lift from the van of O.B.Ross. The driver had been delivering and collecting shoes for repair. This meant sitting on the floor of the van, among all the shoes.

“Latterly, Christine and I got a lift on a Monday morning in a very smart sports car, driven by Lieutenant Commander Nimmo, who was on his way to work at Arrochar Torpedo Range. We always felt he drove extra fast over the bumps to see our reaction!

“On the whole, we were a well-behaved group of children. I only remember one occasion when we decided to be naughty, and hid in the woods at the back of the school.

“It would have been springtime, and primroses and violets were in bloom. Our teacher realised where we had gone, and without much difficulty, collected us all back into the classroom.

“What an amazing small school that was, with many of the pupils going on to have interesting careers.

“Among them — a surgeon, an opera singer, a boat builder and fisherman, head of personnel with an insurance company, occupational therapist and artist, silversmith and jeweller, a photographer, and an engineer.

“It was a happy time for me, and only because of the war.”

Alan Brough

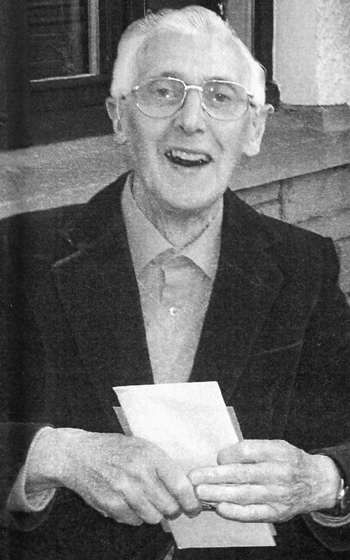

Alan (pictured left in 2007), whose sketch of the school is at the top of this page, was a wartime evacuee from Edinburgh who came to Finnart to stay with his uncle, Charlie Stark, who was gamekeeper at Arddarroch, and his family. He became a pupil at Glenmallan School, aged 10, from early September 1939.

“Being evacuated to Finnart for safety reasons was somewhat ironic, as not long after I arrived, a detachment of ‘Ceebees’ (American military construction battalions) appeared at Finnart.

“Their task was to organise the construction of jetties and oil storage tanks about 100 yards from my uncle's house — a much more likely target for bombers than Edinburgh!

“Along with other evacuees, we swelled the numbers at Glenmallan School from about five to around 15.

“Jean Stone's description of the ambience of life there is better than anything I could provide, but I would reinforce her assessment of Miss Ferguson and Miss Hattle as the best teachers you could imagine.

“I will focus instead on a few incidents that come to mind.

The stray torpedo

“Loch Long at this time was host to a Torpedo Testing Range. The torpedo under test was fired from a pier at the head of the loch, and was supposed to run five or six miles straight down the loch.

“It was monitored by observers on floating pontoons, anchored at half-mile intervals along the centreline of the loch. At the end of the run, a buoyancy tank in the form of a dummy warhead brought the torpedo to the surface, to be retrieved by a picket boat.

“One day, a stray torpedo launched itself up the beach in front of Glenmallan School, puncturing its dummy warhead, and revealing that as an additional insurance against sinking, it was filled with table tennis balls. Quite a few of them were commandeered for local use!

Herring harvest

“On a few occasions, anti-shipping mines were exploded in the loch during tests. An unfortunate result of this was lots of dead fish. In a walk of a few yards along the tide line, you could collect half a bucketful of young herring.

“This provided a wonderful augmentation of our wartime rations. It made a welcome change from whale meat and tinned snoek, which I think is Africaans for tuna.

Assault on Miss Ferguson

“I still cringe when I think of this incident. It was a cold winter's day, and Miss Ferguson was adding coal to the stove, and bending over the waist-high guard rail to do so. I was at a nearby desk, and I feigned as if to smack her bottom.

“Some of the class signalled to me to do so, and I did. I had never before seen Miss Ferguson angry. She straightened up, looked at me and said: ‘Don’t ever do that again!’ I was very subdued for a few days, but I'm glad to say I never saw her angry again.

Mr ‘D.L.’

“Mr Dalziel was in hindsight a gently eccentric man, whom we called a hermit. He was an amateur astronomer, and had quite a large telescope. He put up with us quite amiably when we pestered him for a look through it.

“He would try to put us off by saying he wasn't observing that night, because the moon would be entangled in bracken on the Saddle, a distinctive hill on the far side of the loch. As I remember, he lived in a very small cottage at the north end of the relatively flat ground at Glenmallan.

The Dresden Hymn

“Miss Ferguson took on the daunting task of teaching us part singing. The tune she chose was called the Dresden Hymn, and she divided us into melody singers and descant singers. I can still remember both parts to this day.

“The odd part about it, given the circumstances at that time, is that this is the melody to which the German national anthem is sung — Deutschland Uber Alles! Anyway, it's a fine rousing tune.

Arddarroch Community Dances

“These dances took place in the garage of Arddarroch Estate. This was quite large, having been designed, I presume, for horse-drawn coaches. With the two Rolls- Royce cars abandoned to the weather, the building made a fine dance-hall.

“The connection with Glenmallon School was via one pupil, Rae Bolton, who was a fine accordian player, and in demand to provide dance music. The dances were mostly to Scottish country dance music, like the St Bernard's Waltz, Dashing White Sergeant, Petronella, Eightsome Reel, and Strip the Willow — known to us as Strip the Widow!

Miss Hattle and The Arts

“Miss Hattle did her best to interest us in music and poetry, and I think she would be pleased by the effect she had on her pupils.

“She taught us a melody by an American composer called Edward McDowall. The melody was called ‘To a Wild Rose’, and I still love it.

“I can't remember learning any words for it, which makes me wonder how we learned the tune. Was there a piano in the school? I simply cannot remember.

“Poetry-wise, I still shiver when I hear the first line of ‘The Listener’: ‘Is there anybody there said the traveller, knocking on the moonlit door?’

“She wasn't so successful with ‘Overheard on a Saltmarsh’, which was very twee and not to the taste of ten year-old boys, especially as we had to recite it with emotion and exaggerated pronunciation. It probably did wonders for our elocution, but not for our street cred.

Martinet teacher

“Sometimes we had a replacement teacher when either Miss Ferguson or Miss Hattle was off for any reason. The replacement was Mrs Black from Low Craggan farm at Glen Douglas.

“She kept order in a different way from our regular teachers, and was more like a ‘normal’ teacher. One of the pupils was her daughter, Lorna, and she had to sit up straighter than anyone else. We were all very pleased when our usual teacher returned.

The walk to school

“The walk was never boring. The Whistlefield contingent set off along the road, and after about a mile were joined by the Portincaple children, who had walked a mile up from the shore along a rough footpath through the woods.

“The two groups converged at the top of Finnart Hill, from where the road descended very steeply (200 feet in ¼ mile).

“Near the bottom of the hill were the gates of Finnart and Arddarroch Estates, where the next group of people joined the caravan. From here, it was only a mile along the winding road, with its ups and downs before the final drop to Glenmallan.

“Every part of the road had its name: Deil's Den, Windy Corner, Witches' Hollow, The Steeple, and so on. Deer and otter were sometimes seen, and dolphin and porpoise could be heard blowing out on the water.

“There were rituals to be observed along the way: special bits of wall to be walked on (some with drops of 15 feet to the shore or the rocks), stretches of lochside rocks to be jumped along, loops of woodland to be walked through, etc. No, it wasn't boring!

Snowbound

“During the winter of 1940, the road from the Gareloch to Loch Long was blocked for several weeks, because of heavy drifting snow — perhaps nothing to Canadians, but a big event for us Scots. It certainly closed the school.

“After a week or so, supplies in the Finnart area were running low, and a backpacking expedition was organised for the 3½ mile walk to Garelochhead. I remember seeing the snow banks well above my head, as I trudged along in the trench the men had cleared — probably organised by John McGlone.

“After the snow stopped, we had several days of clear frosty weather with a full moon at night. It was magic! The entire Finnart and Arddarroch community spent glorious moonlit nights sledging on Finnart Hill.

Supplies from across the Atlantic

“The tankers which arrived to unload at the end of my uncle's garden brought more than oil from Canada and the U.S. Many of them carried fighter aircraft — Thunderbolts and Mustangs — as well as tanks, cocooned in doped fabric.

“More important for us kids, they brought Hershey bars, white bread, bananas and sugar, all of which were either not available, or were strictly rationed.

“Many of these tankers never returned, as they suffered heavily from U-boat attacks on the convoys across the Atlantic.

Final thoughts

“This exercise has been very enjoyable . My memory has worked quite well, I think, apart from not being able to remember how to spell ‘remember’!

“Rae Bolton, Joyce Russell and I must have been the scourge of Finnart and Arddarroch, as we used to range through the woods and rhododendron jungles of the two estates with home-made bows and arrows.

“No bracket fungus was safe — they made wonderful targets. I'm sure Winnie Bolton thought we were a menace.

“I returned reluctantly to Edinburgh, in 1942, I think. Curiously, the school I attended there was called Darroch Junior Secondary, whose name reminded me of Arddarroch.

“My brother David worked for four years during the war at the Rolls-Royce factory at Hillington, building Merlin engines for Spitfires and Lancasters.”

School group names

1939: Miss Ferguson — a wonderful teacher; Rae Bolton; Agnes Kirkwood — a Glasgow evacuee, who stayed at Arddarroch; Jean Stone; Christine Stone (at front); Peter McKichan — son of John McKichan, fisherman at Portincaple; Graham McGlone — he left Glenmallan School soon after; Sheila Anton; Herbert Gray — lived at Portincaple; Jessie Ronald; Norma Anton; Joyce Russell — Glasgow evacuee, who stayed at Arddarroch; Maybeth Stevenson — lived at Portincaple; Alan Brough — Edinburgh evacuee who stayed at Arddarroch; Willie Dawson — father had been head gardener at Rosneath Castle, then at Arddarroch.

1940: Sheila Anton — stayed at Whistlefield; Maureen Devlin; Peter McKichan — son of the fisherman at Portincaple, who used to take Finnart and Arddarroch community on picnic outings on his boat; Isabel Craig; Jean Stone (at front); Betty Bowie; Willie Dawson — son of a gardener at Arddarroch Estate. Family came from Yorkshire. Willie's brother, 2-3 years older than him, died about this time from leukaemia, despite frequent blood transfusions from his father; Miss Hattle — a wonderful teacher; Ria Beattie — a Glasgow evacuee who stayed at Arddarroch. Married young. Father worked at Singer's; Jimmy Beattie — Ria's young brother (at front); Rosemary Cameron — stayed at Strone Cottage. Died young; Elspeth Devlin; Rae Bolton.