THE STORY of Helensburgh’s water supply begins with the town’s first Provost, steamship pioneer Henry Bell.

This inventive genius first suggested the idea of bringing a piped water supply to the town.

This is yet another subject researched by local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre, who provided much of the detail which follows.

In the early days of Helensburgh, water for public use was obtained mostly through wells, formed by digging into the underlying soil and bedrock until water was struck.

Wells were distributed throughout the town, and were generally operated by hand-operated pump, the spout and handle being made of iron.

Fetching, pumping, drawing by bucket and carrying water just for the needs of daily life must have been an arduous and never-ending chore.

Responsibility for the upkeep of wells could be a contentious issue. In 1851 Helensburgh Town Council refused to maintain wells, and management was for some time in the hands of the local police.

A Town Council minute of 1810, when Bell was Provost, refers to the concept of forming a reservoir, with water being led into the town via two branches — one down Sinclair Street, and the other down James Street.

It is hard to see beyond Bell as the driving force behind this plan, especially as there are accounts of how Bell and his assistants surveyed, measured and pegged out a suitable site in Glen Fruin, the intention being to form a reservoir in the vicinity of Kilbride Farm.

Although farmland would have been inundated, the concept was sound in principle. The glen is constricted at that location, and it would have been a logical spot at which to build a dam.

This was not the first time Bell had been involved with water supply. In 1806, the great engineer Thomas Telford had been tasked by the City of Glasgow to draw up plans for a water supply, based on drawing water from the River Clyde at Dalmarnock.

In response, Bell came up with a counter plan, complete with costings. His big idea centred on abstracting water from the River Clyde near Lanark and feeding it by canal to a reservoir above the city, prior to onward distribution.

The elegance of Bell’s plan is that it would have been gravity-fed, while that of Telford required pumps. In addition, Bell claimed that abstraction of water at Dalmarnock would risk heavy contamination, while his water would be relatively pure.

In the event, it was Telford’s plan that was taken up, while Bell’s proposal was set aside. As in the case of Glasgow, so too at Helensburgh, the plan of 1810 being left to lie on the table.

In Bell’s day the powers of the Town Council were very limited. The book “The Story of Helensburgh” — c.1895, anonymous, but commonly believed to be the work of long-serving Town Clerk George MacLachlan — states: “The Town Council had no powers of taxation for any purpose, or any source of revenue, except what arose from the dues of fairs and markets.”

The trouble with Henry Bell seems to have been that he was decades ahead of his time. He was not a wealthy man, and he was not in a position to finance his vision.

In 1810 he mortgaged his Baths Hotel for £2,000, and what money he possessed would have been earmarked for his pioneering steamboat project.

Over the years the Town Council did discuss the idea of a better water supply from time to time, but no serious attempt was made to progress the matter.

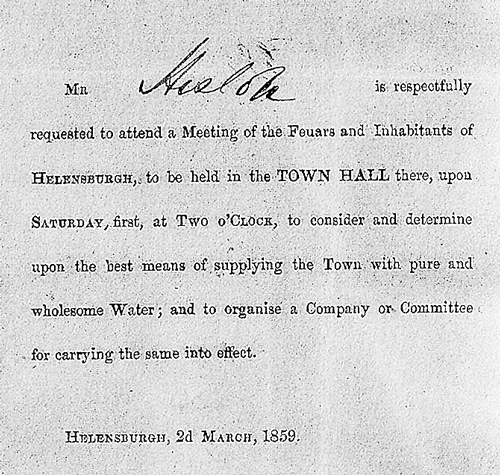

A proposal was made in 1859 at a public meeting by Dr Robert Hendry, then a Bailie, for the construction of a reservoir in the upper reaches of the Glennan Burn, but it was concluded that the supply obtained would be inadequate.

The town was by then connected to the railway, and the population was now over 5,000, so it became clear that fundamental change was needed. One writer commented that the pace of growth in the town was being slowed by the lack of a proper water supply.

Several events around this time may have helped to bring about decisive change. In 1862, the passage into law of the General Police and Improvement (Scotland) Act held out the prospect of increased powers for town councils.

The Act enabled such bodies to cherry-pick any or all clauses in matters like water supply, drainage, cleansing, and so on, along with the necessary powers to implement them.

In fact, the clauses in the 1862 Act pertaining to water were adopted in 1866, and the virtue of this Act is underlined by the fact that by 1875, Helensburgh had adopted all of its clauses.

Another factor which may have helped progress plans for a water supply stemmed from events at Milligs Mill in what is now Hermitage Park. The Mill was water-powered from Milligs Burn.

There was a small reservoir a little above the Mill, but this was augmented by two good-sized reservoirs on Blackhill, located at the same site as the later town reservoirs. These are clearly shown on the first edition of the Ordnance Survey maps, surveyed in 1860.

The Ordnance Survey’s own records state that the function of these reservoirs was to supply water for a ‘flour mill’. There was a similar set-up at Rosneath, where the mill dam for the corn mill at Millbrae and sawmill at Camsail was augmented by supplies from the large Lindowan Reservoir.

In 1862, Milligs Mill introduced a steam engine. Photographs show a factory-style chimney at the site, doubtless to lessen smoke pollution from the engine, which would have been coal-fired.

With the Industrial Revolution in full swing, big city mills were making it increasingly difficult for small provincial mills to compete, and the introduction of the steam engine may well have been an attempt to help keep Milligs Mill afloat.

Another factor which may have influenced thinking on the need for a piped water supply is that of public health. In 1832, Helensburgh had been hit by Asiatic cholera, in the first devastating outbreak of that disease to hit Great Britain.

It came to be greatly feared, being no respecter of age, sex or station in life. For example, the 24 year-old son of a building contractor was taken ill in Helensburgh, and was reportedly dead within seven hours of the onset of symptoms.

In the next big outbreak, in 1849-49, the Oddfellows Hall was turned into a cholera hospital. Similarly, in 1866 a room above the Town Hall was used for that purpose. The authorities were taking the threat posed by cholera very seriously.

By the 1850s, John Snow, a medical man, in a fine piece of investigative work demonstrated a clear link between occurrence of the disease and usage of particular public wells.

The authorities in Helensburgh would have been well aware of his findings, and there is evidence of their vigilance, with wells from time to time being condemned as unwholesome including those at Alma Place and Havelock Place in the 1860s and 1870s respectively.

Not only would a controlled supply of wholesome piped water help address the menace of cholera, it could also pave the way for the introduction of a comprehensive drainage system, as shortcomings in sewage disposal could easily contaminate groundwater and wells. So a public meeting was called.

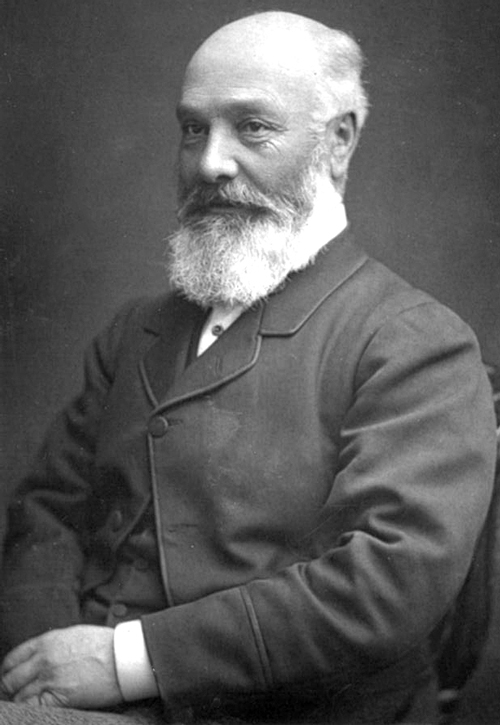

What was named the Mains Hill water supply was progressed and formally opened on September 26 1868, particular credit being given to Donald Murray, convener of the Water Committee, and Provost Alexander Breingan (right), whose wife declared the facility open.

The official opening was a colourful affair, with a large procession, music, speeches and toasts, the town being described as “en fete”.

The mill dams above the town appear to have been incorporated as the basis of the town reservoirs, although a good deal of work would still have been required, including installation of valves, filters and pipes, together with work on dams and embankments.

The lower reservoir, next to the Luss road, was designated No.1, while the other to the north, was designated No.2.

A vociferous minority were fiercely opposed to the scheme. The history of local public water supply throughout the district is one of opposition at every twist and turn.

One commentator said opposition to the Mains Hill scheme came from three sources: those content with existing arrangements, those who felt that the location of the reservoirs was wrong, and those who felt that the scheme should not be brought in under the 1862 Police Act.

In 1866, a plebiscite had been held on whether or not to adopt the water clauses of the Act, when the proposed measures were approved by only a small majority.

Of course, those entitled to vote at that time represented only a small proportion of the town’s population — male householders with property worth at least £10 a year.

More than likely, the single biggest cause of dissent stemmed from the effect on town rates, because of course the new supply came at a financial cost.

The new municipal water supply was adequate for a few years — but by 1893 there were complaints about the water in the west end of the town.

One resident wrote: “The water is dirty, is not presentable at table, and is unsuitable for washing.”

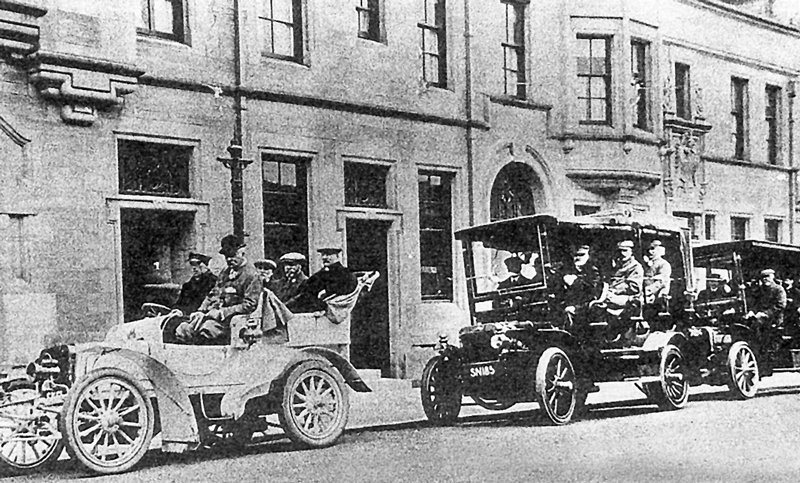

The system was inspected annually by town councillors and officials — a jolly trip which usually ended in a dinner. The 1896 participants are pictured (above), and (below right) the 1910 party leaves from outside the Municipal Buildings in Sinclair Street.

The existence of a piped water supply also saw the introduction of another feature in the town landscape.

Ever since the introduction of the piped supply, the old wells had been gradually disappearing. However, in their place appeared a new facility, gravity-fed public drinking fountains.

Some, like those at Colquhoun Square, were housed in attractive polished granite structures, while others, like one at Kidston Park, were in beautifully formed cast-iron mountings, produced at works like the Saracen Foundry in Glasgow.

The period 1903-06 saw major upgrading of the water supply, with the firm of Baptie and Bonn chosen as engineering consultants.

No.1 reservoir, the one closest to the main road, was upgraded, while No.2 reservoir, lying to the north, was greatly increased in capacity to hold double the water of No.1.

A completely new reservoir, designated No.3, was built higher up the hillside than the others, although it had a much smaller capacity. At one stage, at least 80 men were involved in carrying out the work.

In September 1914 the start of the Great War brought with it quite different challenges. Reservoirs and waterworks were perceived as being among possible targets for saboteurs, and, as recommended by the Chief Constable, one man was put on watch at the site during daylight hours, with three at night.

In September 1914 the start of the Great War brought with it quite different challenges. Reservoirs and waterworks were perceived as being among possible targets for saboteurs, and, as recommended by the Chief Constable, one man was put on watch at the site during daylight hours, with three at night.

It is not known for how long this arrangement lasted, and no information has come to light about any attacks on local reservoirs, railway bridges, and so on.

Another wartime measure was the cutting of grass around the reservoirs by A. and R.Spy, coal merchants, to be used as feeding for their horses — a fine example of husbandry of available resources.

In 1930, Glen Fruin was the scene of a further extension to the town’s water supply, when Blairnairn Burn was tapped for water in a similar way to the arrangement at Ballievoulin.

As the years passed, more and more attention was paid to health and safety issues. Chlorination of water was introduced in the 1930s, while old drinking fountains were increasingly replaced by their sanitary drinking equivalents, which amounted to gradual phasing out of the time-honoured iron cup, secured to its mounting by a stout chain.

In the spring of 1951 the members of Helensburgh Business and Professional Women’s Club were given a conducted tour of the town’s water supply, and an account of this outing has survived.

It provides a first class, non-technical description of the system as it existed at that time.

The day began at Glen Fruin, the ladies having been taken there in buses. Their guide for the day was Mr Little, the Water Department’s foreman.

The account reads: “A quite stiff pull up the hillside from above Blairnairn Farm brought us to the catchment on the stream, where there was a weir.

“Water was drawn off from there, and, passing through metal screens to clear it of gravel and sediment, was led into a well-house. Here, there was an automatic control valve with a gauge, registering volume of water.

“This was linked to charts, giving continuous readings on a graph over time, and was powered by a mechanism akin to a timepiece of old, set by pulling down a heavy weight. This was re-set once a month.

“There was also a rain gauge here, as well as two others higher up the hillside. These had to be read twice monthly — quite a business in bad, and especially snowy, weather.

“The piped water from Blairnairn Burn joins that from Ballievoulin Burn at Craig’s Pool on Fruin Water, and one 8-inch pipe brings the water down to the reservoirs.

“Of those there are three: No.1 is that nearest the town, and it holds 25 million gallons. No.2 is higher up, and it contains 50 million gallons. No.3 is yet higher, and it holds 5 million gallons.

“By virtue of its height, it is this one that has the pressure to supply Helensburgh above the Upper Railway Station. Farms in Glen Fruin are supplied direct from the main pipe.

“The total of 80 million gallons seems a lot, but not so much when we heard that the town’s consumption is up to 900,000 gallons over 24 hours. We were told that nationally, 30 gallons per person per day is reckoned a good average consumption, but Helensburgh’s was 80 gallons per day.

“A total of 21,000 gallons was used during the night, a large amount for a town without the heavy calls made by industry. It was thought the gasworks, the railway, and the hospitals might account for some of this.

“There was reckoned to be little risk of a water shortage in Helensburgh, as the reservoirs normally held 80 days supply.

“We stopped at the filter houses, where there were endless things to see. We saw the well, where 60,000 gallons of water per hour are forced through a series of very fine metal mesh screens. The metal, an alloy of nickel and copper, is called monel.

“This is immensely strong, but even so, careful watch has to be kept for damage caused by heavy sediment, and one part or another may need to be renewed.

“The broad rims of the screens are made of brass, and when we remarked on their beautiful polish, the foreman said it was the work of a man! The spick and span appearance was a tribute to the work of the foreman and his staff.

“Outside the filter house, Mr Little showed us the clean, filtered water coming over the weir. Chlorine is added to the water by means of a rubber tube, after filtering, and the proportion is very small, being only 4 lb per million gallons.

“Chlorine may be reduced a little in winter, and stepped up slightly in summer, to avoid the risk of bacteria. In the Swimming Pond, where the risk has to be carefully watched, chemicals are added in five times as great a proportion.

“The water is led down Sinclair Street in two 8-inch pipes and one 10-inch pipe, these branching off into the network of smaller piping. Most of the piping is now of steel.

“We were shown a second filter house, taking water from No.3 reservoir and supplying the upper part of the town. It worked on a different system, being based on sand filters.

“In each of two very large sand filters, water from the reservoir is forced up and down through seven tons of sand, and 144 little revolving metal tumblers, holding pebbles, whose movement helps with the scouring.

“We watched the gauges showing pressure at intake and output, and we saw how small the variation was between the two, the needles in both keeping very close to 40 lb per square inch.

“Mr Little isolated one tank, and set in motion the machinery by which the tanks are washed out once a week by a pump, which draws water down from the main tank outside, and forces it up through the filter tank, by six rotary arms radiating from a metal column drive by a motor arm.

“This is a noisy, draughty process, and made us realise the force involved. Going outside, we could see the strong gush of brown water being discharged into an old tank, before being led into a sewer.

“We were able to examine the rain gauges, the meteorological gauges and the sun recorder. There was also a maximum-minimum thermometer.

“Notes on cloud formation are recorded, as are wind speed and direction, and hours of sunshine, and information is sent monthly to the Meteorological Office in Edinburgh.”

An increased demand for water was anticipated, and so the Town Council began to think about how this challenge could best be met.

One proposed solution was to link into the Auchengaich reservoir, located in a side glen at the upper end of Glen Fruin. This had been built by the Royal Engineers during World War Two, when the whole district saw a massive increase in military presence.

Credit for the construction of Auchengaich has been largely attributed to the efforts of a Rhu resident, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Barge, who saw clearly the wartime strain that was being put on the water supply. When completed, Auchengaich supplied much of Garelochside, but not Helensburgh.

In early 1967, prior to the Town Council losing its remit for water supply, it was agreed to proceed with incorporating the water supply from Auchengaich, in partnership with Dunbarton County Council, which was also anxious to see the scheme go ahead.

The County Council was responsible for water supply outwith the burghs, although it too surrendered its remit in 1967 when thirteen Regional Water Boards were set up.

Another change that took place before the new Water Board took control was the decision to construct a new filter station and associated facilities to replace the filter stations and pump house located at Walker’s Rest, near the top of Sinclair Street, on the east side.

Possibly the projected increase in town population size was the main driving force behind the change, but whatever the reasoning, the new facility on the other side of Sinclair Street was erected in 1966-67.

A final council water inspection trip, the first for 17 years, was led in April 1968 by Provost J.McLeod Williamson, and the party is pictured (above) outside the front door of the Municipal Buildings in East Princes Street

Another matter which demanded attention in the years leading up to the inception of the Lower Clyde Water Board was the vexed question of whether or not to add sodium fluoride to the water supply.

It was argued that this move would help protect teeth, especially in the young, but the topic proved hugely controversial right across the country.

In 1964 the Town Council decided not to add fluoride to the water, but the tide was turning, and early in 1966, the County Council made the decision to accept in principle the addition of fluoride to water.

With the coming of Lower Clyde Water Board, this body too came to the same decision.

The Water Board itself did not have a long life, being supplanted in 1975 by the advent of nine regional councils, one of which was Strathclyde Regional Council, with water supply forming one of their functions.

In 1995, with the demise of the regional councils, control of water supply was vested in three bodies, the local one being West of Scotland Water. These organisations were themselves dissolved in 2002-03, when Scottish Water, responsible to the Scottish Government, took over.

Today No.2 (above) and No.3 reservoirs lie drained and disused, while No.1 reservoir does contain water, but no longer functions as a water supply, being used as a fishery by the local angling club.

Along with a smaller number of reservoirs has come a steady linkage across those in use. The system now allows water to be accessed from a variety of sources, as the need arises.