A CENTURY ago a steady flow of visitors beat a path to the door of Susie and her ‘Castle’, an upturned half-hull of a fishing boat on the shore at Portincaple.

Postcards showing her and the unusual dwelling were prepared and sold well. However, Edwardian excursionists soon found out that the short crossing of Loch Long from Portincaple brought them to the home of another notable person.

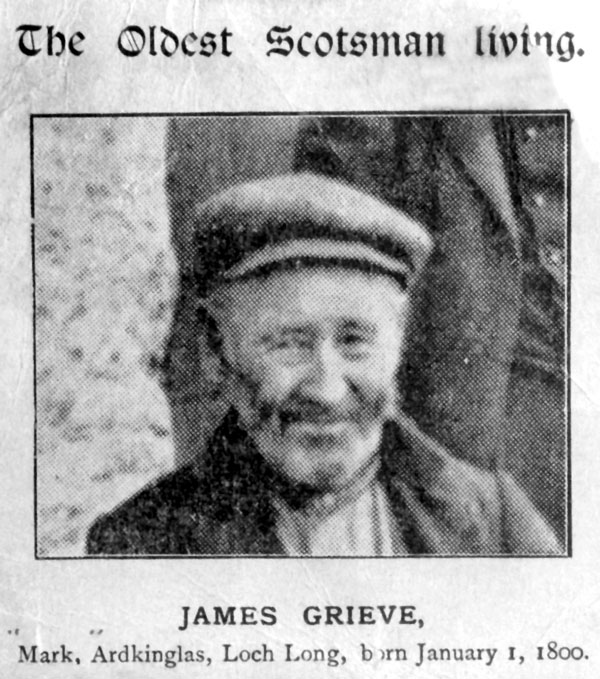

James Grieve was billed as Scotland’s oldest man. As with Susie, so with James — their lives have been immortalised through postcards.

The story of the life and times of James Grieve provides a glimpse into the world of the hill shepherd in some of the remotest parts of Scotland, while at the same time shedding some light on an extremely turbulent period in the history of the West Highlands.

Local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre has researched the story of James, who was not quite the person he appeared to be.

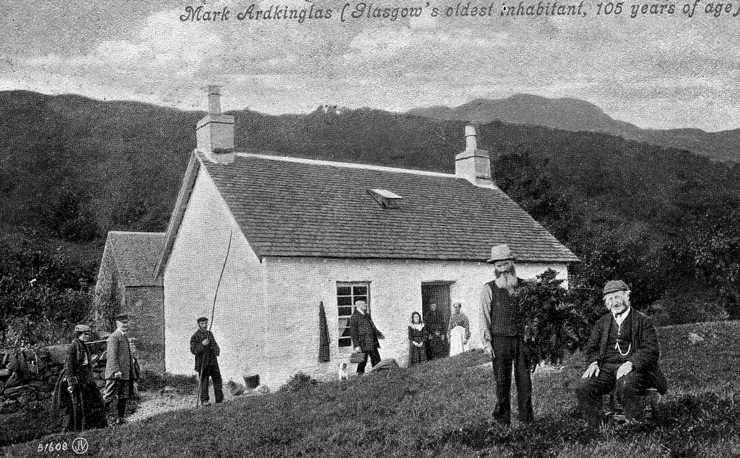

In 1903 James joined the household of his son, William, at Mark, a little cottage standing on a headland by the shores of Loch Long, diagonally across the loch from Portincaple.

William had moved there with his own family the year before, and he was employed as a shepherd with Coilessan Farm. Sitting at the foot of the rugged stretch of hill country known as Argyll’s Bowling Green, the setting of Mark could hardly have been more spectacular.

An important factor which goes some way to explain the publicity that came to surround James was the gifting in 1906 of a large tract of land, including the Bowling Green, to the City of Glasgow by its then owner, A.Cameron Corbett, later Lord Rowallan.

This followed the sale of the large Ardkinglas Estate the year before in two portions, Corbett having purchased the smaller of the two. So Mark and its surrounds came under Glasgow Corporation’s parks department from that time onwards.

This even led to the proud boast that James was Glasgow’s oldest citizen!

In July 1910 James was visited by two reporters from the Glasgow Herald, and their account appeared in the issue of July 14. This, and his obituary published on November 29 that year, tell his story.

The first article stated: “James Grieve, the Argyllshire centenarian, is in very feeble health. He has taken to his bed, and contrary to his usual self, is disinclined to all forms of activity. He has now reached the age of 110 years.

“A native of Invergarry, he came southwards early in life, and spent long periods as shepherd about Dalmally and Callander. He was first brought into prominence while staying with his son, shepherd on Mark Farm, Loch Long.

“At Whitsunday last, the son went to Corantee Farm, Loch Eck, the old man going with the family. But about three months ago, he gave up taking an interest in what was going on amongst the sheep.

“He is being faithfully visited by the Rev Mr McKinlay, parish minister, who has taken a great interest in the welfare of the old man.”

The obituary, headlined “Death of Oldest Scot”, stated: “James Grieve, aged 110 years, died at Corantee, Loch Eck, on the Benmore Estate.

“Born at Glengarry, Inverness-shire, he was 15 years of age when Waterloo was fought, and well remembers the rejoicings when the great victory was announced. He assisted in carrying wood and peat to the summit of his native hills to make the bonfire at that time.

“Up until last year, Mr Grieve was able to go about. He was a great smoker and was not a teetotaller. He had all his faculties to the end. He is to be buried at Kilmun Cemetery tomorrow.”

Quite different in tone is the recollection of a visit early in the 20th century, quoted in the book “Tea at Miss Cranston’s”, by Anna Blair, published in 1985.

It records: “We used to take a wee boat across Loch Long and beach it on the shore near a cottage where an old man lived. He would have been maybe some ninety-eight years old the first time we were there, then up to a hundred and one in the next three.

“It was quite the thing for holiday-makers to go and just look at this old chap, sitting outside the cottage and selling postcards of himself as souvenirs.

“And ‘How are you the day?’ you used to ask. ‘Och I’m fine, fine,’ says he. Same thing every time. He just made a living out of being a hundred. He was there for viewing beside his wee cottage on the shore.”

In 1954, local historian John A.Stewart had a letter published in the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times, following up on an earlier letter by him asking for any information about Grieve.

His initial interest had been sparked on being shown an old postcard taken at Mark, featuring the old man, then aged 105 years.

His letter notes that as a centenarian, James was able to climb the hill at Portincaple and take the train to visit some Cameron friends, possibly relations, near Invergarry. The father of James Grieve was stated to have left Kelso for Glengarry, when a youth.

It was also claimed that, as a youngster, James could remember old men who had fought at Culloden.

Another story is that, at the age of ninety, James was at Dalmally market, looking for a single shepherd’s job — he was evidently by then a widower.

It is also said that William, the son, was sometimes mistaken for the father. The confusion probably stemmed from the fact that William sported a large white beard and moustache, while the father was clean-shaven.

That is the legend of James Grieve. But how well does the story match what is recorded in the official records?

A good starting point is the death certificate. The date of death is given November 26 1910. It states that his father was Walter Grieve, shepherd, while his mother’s name is given as Catherine, maiden surname McDonald.

He was the widower of Annie McCallum. The informant was William, the son of James. Crucially, the age of the deceased was given as 110 years.

A search under the less common surname of Greive produced a birth certificate of a James Greive, with Walter Greive, shepherd at Glencuaich, as father, in the parish of Glenelg, Inverness-shire.

However, the date of birth was not around 1800, as would have been expected, but was given as November 1 1814, with baptism taking place on January 22 1815.

The same parish records were also found to contain the birth of a son, William, to a Walter Grieve, shepherd at Glenquaich, on November 11 1810. It looks very much as if Walter Grieve and Walter Greive were one and the same person.

Glenquoich, the spelling used today, is in the upper reaches of Glengarry, a place-name that chimes with the Glasgow Herald obituary article.

According to John Stewart’s letter, the father of James Grieve left Kelso for the Glengarry area when in his youth. If this is true, and that the father was the Walter Grieve who registered the birth of two sons at Glenquoich in 1810 and 1814, the move to the Highlands for work evidently took place prior to those dates.

As far as the age of James is concerned, there is considerable discrepancy in the ages supplied in census records over the years. But nowhere is there anything to support the idea that he would have been a centenarian by the early 1900s.

The big question is how did it come about that James Grieve became known as a centenarian, when he was nothing of the sort?

The ages he claimed to be over the years varied wildly. It could be that with advancing years, he might have become ever more uncertain.

But what of the Glasgow Herald story about helping to set a bonfire celebrating victory at Waterloo? Could it hold the key to the mystery of Grieve’s erroneous age?

With a birth date of 1814, it is easy to imagine James Grieve being exposed to tales about the Waterloo celebrations as he grew up. As he aged, it is possible the perception came about that he had actually been a participant. It may even be that over time, he began to imagine that this was so.

Stranger things have happened. Once that leap had been made, it would be necessary to give a birth date which fitted the tale. That might help explain a report that he was born on January 1 1800.

It is unlikely the truth will ever be known for certain. But that might not really be a bad thing — the best stories always have an element of mystery about them.

And as for James, retaining the ability to help at sheep-shearing when he was in his late eighties must be something worth celebrating!