HELENSBURGH has plenty of licensed premises these days . . . but in the 19th century the town and district had early links to the Temperance Movement.

The launch of the movement in the 19th century reflected a growing awareness that society was being blighted by a culture of excessive drinking, and that some form of grassroots action was desperately needed.

The first temperance society in Great Britain was formed in 1829, and local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre has been researching the local links to the movement almost from its beginning.

Prior to the emergence of organised temperance, some voices had already been raised about the negative effects of alcohol consumption and the temptations that might draw people in that direction.

The Old Statistical Account of Scotland gives some local context. Produced in the 1790's, it provides descriptions of life in every parish, drawn up by ministers of the Established Church.

The account for Row — now Rhu — parish, written by the Rev John Allan, in 1790, states: “A few individuals are much addicted to dram-drinking. There are eleven ale or rather whisky houses, one properly called an inn.”

While he does not qualify this further, his counterpart at Rosneath, the Rev Dr George Drummond was more incisive with his comments. “There are no ale houses, but plenty of whisky houses, which are rather unfriendly to the morals of the people,” he wrote.

The Rev John Stuart, minister at Luss, wrote: “There are nine licensed ale and whisky houses, and one inn.”

There were many places in the district offering alcohol for sale, and these figures do not take account of the considerable amount of illicit liquor which was being manufactured and consumed.

The whole culture of the country was geared to heavy drinking at almost any opportunity. A study has calculated that in the early 19th century, the average consumption of whisky in Scotland by those aged 15 and over, was almost a pint a week. This staggering statistic refers only to legally produced spirits.

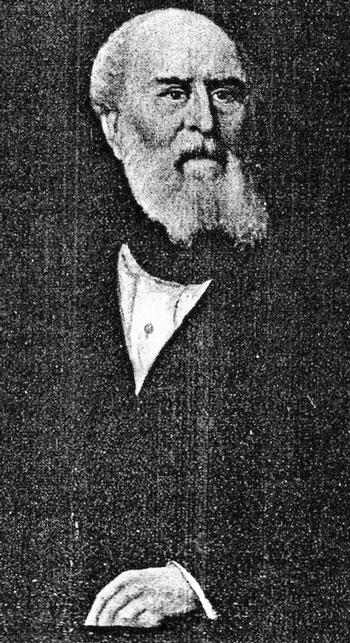

It was against this background that in 1829, a Greenock advocate, John Dunlop (left), founded the first temperance societies in Great Britain.

In October of that year, he formed two societies, one in Greenock, and the other at Maryhill, near Glasgow. Later of course, Maryhill became part of Glasgow.

He seems to have taken inspiration from the fledgling Temperance Movement in the United States, and almost immediately found a willing lieutenant in William Collins, a Glasgow publisher, who not only formed a society of his own, but evangelised in England, establishing societies at Bristol and London within the next two years.

A local connection comes through Dunlop's father, Alexander, a prosperous Greenock merchant and banker, who took possession of the small estate of Keppoch, between Helensburgh and Cardross, and built a mansion house there in 1820.

There is a further local connection in that John's half sister, Helen Boyle Dunlop, married in 1829 the minister at Rosneath, the Rev Robert Story, who himself features in the temperance story.

Helensburgh had its very own Temperance Society as early as 1835. The president was the Rev John Anderson, treasurer John McLeod, secretary Alex. Wilson, along with a committee of six.

The author of ‘The Story of Helensburgh’ in 1894 said of the Society: “The basis was not total abstinence, but abstinence from any liquor stronger than beer. Of what success it had there is no record.

“There was however an early setback, when a temperance lecturer brought along a very small still to demonstrate how whisky was made. This was seized by the local exciseman, and the lecturer prosecuted.

“Later, the principle of total abstinence was substituted for the previous vague pledge, and it was found to be the only workable rule.”

This sums up the shortcomings of the movement in the early days.

Membership of the societies tended to be middle class, and in their call for whisky and other spirits to be shunned, while wine and beer could still be consumed, they were perceived by many to be hypocritical — the working classes were to be denied their refreshment, while the middle classes were at liberty to imbibe wine and beer in the privacy of their homes.

However people like Dunlop were pioneers, perhaps fearing that calling for total abstinence would be a step too far. The fact is that the principle of complete renouncement of alcohol proved a much more winning formula.

It brought into the temperance fold many new people, and a typical ‘teetotaller’, as members were termed, was likely to be a skilled worker, and quite possibly a Chartist — an active working-class political movement. A 'sober' husband was much prized, as this lantern slide c.1900 shows (left).

The accolade for preaching complete renunciation of alcohol goes to Joseph Livesey, a key figure, who began a total abstinence society at Preston, Lancashire, in 1832. John Dunlop sought to bridge the gap with his original philosophy, but William Collins remained more circumspect.

The author of ‘The Story of Helensburgh’ mentions a total abstinence society being established in the town, but he does not give the date of formation and says the leading members were the late Andrew Provan, James Beckett and Donald Dempster.

This is almost certainly a reference to the Helensburgh society that was linked to the Scottish Temperance League, which was founded in 1844. It is not certain when the local society was formed. But it was cin existence by 1862, when it appears in an STL register.

Within the field of complete abstinence, there was debate as to whether the “short pledge” or the “long pledge” was the more appropriate. With the former, alcohol was shunned by the individual only, while with the long pledge, the aim was to avoid placing temptation before others as well.

Did the early days of the movement meet with measurable success in weaning people away from strong drink? This is very difficult to quantify, but the New Statistical Account of Scotland accounts of parish life gives some idea.

In the entry for Row parish, written by the Rev John Laurie, quite a different tone is adopted to that of his 1790's predecessor.

He wrote: “There are about 39 public houses in the parish, a far greater number than ought to have been licensed among a population of so inconsiderable an amount. Nine of them are on Garelochside, where one or two at most would have been abundantly sufficient.

“Considering the rapidity with which the habits of drunkenness are increasing everywhere, it is much to be wished that some effectual means could be restored for checking this fearfully ruinous vice.”

The Rev Peter Proudfoot, minister of Arrochar parish, stated: “There are seven public houses, five of which are worse than useless,and ought to be abolished, but two are necessary — the inns at Arrochar and Tarbet.

“The other five have a most pernicious influence, inducing and maintaining habits of intemperance. It were well for the interests of the community that these were instantly and for ever put down.”

Cardross sounded a more optimistic note, with the Rev William Dunn writing: “Considerable exertions have been made to check the increase of public houses, and excepting in Renton, the number is moderate.”

The Rosneath account, written by the Rev Robert Story was of especial interest, as his brother-in-law was John Dunlop, father of the movement.

He wrote: “Inns — lately there were five, now there are only two, the ferry houses of Row (Row of Rosneath) and Kilcraigin.

“The privilege which this parish enjoys is its magistracy, which resorts to all just expedients for diminishing the opportunities of indulging in the use of intoxicating liquor, and this cannot be too highly valued.

“From this evil, likely to inundate some of the contiguous parishes, by the proprietors encouraging rather than preventing the multiplication of licenses, the people of this parish are comparatively secure.”

Story seems to attribute much of the credit for progress to the principal landowner, the Duke of Argyll. However, up until 1839, the Duke in question was George Campbell, 6th Duke, whose own lifestyle was scarcely a model of prudence and self-control.

Possibly the estate factor exercised real influence here, since the 6th Duke himself was rarely present at Rosneath.

Victorian author W.C.Maughan says of Story: “He was fearless in the discharge of his duty, bravely encountering dangers from ill-disposed parishioners, who resented his vigorous denunciations of their drinking and smuggling propensities”.

The 7th Duke was pro-active in his outlook. Battrum's 1864 Guide to Helensburgh stated: “Aside from Rosneath Ferry inn, there is not an inn, lodging house or shop on the Peninsula where a single lawful glass of whisky can be obtained.

“This is no great deprivation, probably, but an illustration of the possibility of a pretty large and populous burgh thriving under the Maine liquor rule, which the advocates of temperance seem largely to have forgotten.

“This has been the case now for some time, and we suppose that so long as His Grace, the Duke of Argyll, continues to rule in his own lands, it will remain so.”

Licensed grocers on the Peninsula did sell alcohol, though this was limited to the likes of ale and porter.

Initially at least, both the Church of Scotland and the Roman Catholic Church had reservations about the movement, although later they came aboard. The Free Church of Scotland, from its formation in 1843, along with the United Presbyterians and Baptists, showed more enthusiasm from an early stage.

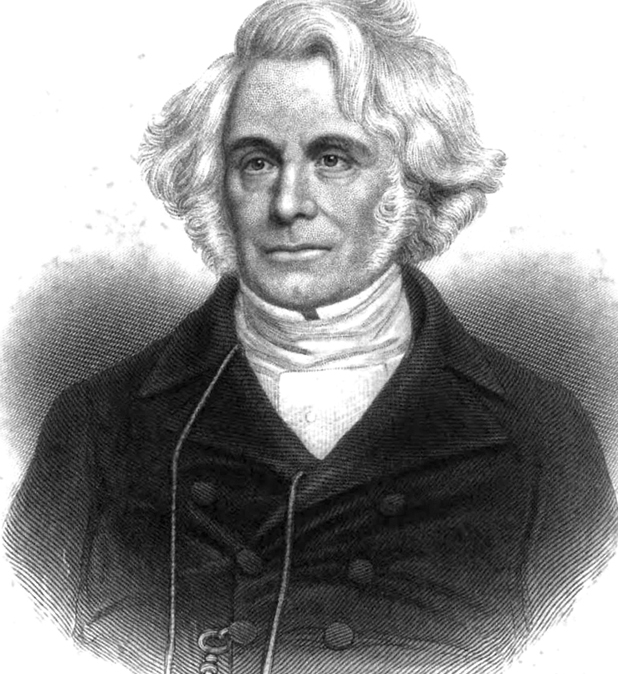

While organised temperance depending heavily on powerful oratory for putting the message across, it was an Irish Catholic priest, Father Theobald Mathew, who is recognised as being the most gifted of all the speakers.

When he came to Glasgow in 1842, vast crowds came to hear him speak, and almost certainly, these would have included people from the Helensburgh area. Distinguished historian T.C.Smout has observed that this occasion provided a rare instance where the deep sectarian divide in the city was briefly set aside.

The main thrust of the early movement was geared to weaning people away from alcohol through the power of persuasion. But it was also recognised that inns and pubs constituted the few places where people could go to in order to socialise.

So steps were taken to provide suitable alternatives — among them coffee shops, tearooms and temperance hotels.

The Cranston family were especially notable in Scotland for their efforts in this field. There were many temperance hotels, and Helensburgh and most other communities in the area had at least one temperance hotel.

It can be argued, though it is hard to prove, that provision of amenities like public parks, libraries and community halls could have been influenced by the movement to a degree.

It certainly had a role in encouraging alternative beverages to alcohol, such as soft drinks, with Helensburgh boasting a number of soft drinks factories, such as Lily Springs and Fairy Springs. Pubs began to offer soft drinks to customers from the 1860s.

According to Smout, the movement, praiseworthy though its efforts were, had little measurable impact on the amount of alcohol actually being consumed. He argues that legislation and fiscal policy had much more tangible results.

For example, the Licensing (Scotland) Act of 1853, better known under the name of its main proponent, William Forbes McKenzie, had a profound effect on drinking habits. The Act was strongly influenced by temperance considerations.

As Conservative politician, McKenzie was elected as MP for Peebles in 1837. Noted for his advocacy of Catholic and Jewish emancipation, it was as an MP for Liverpool that he was to successfully introduce his Licensing Bill in 1853, which overcame the various hurdles before becoming law that year.

The Forbes McKenzie Act brought about changes which survived until the 1970s. For instance, there was the famous clause that on a Sunday alcohol could only be sold to bona fide travellers, causing some to resort to the Clyde paddle steamers in order to quench their thirst.

The hours of pub opening were curtailed, for example being required to close by 10pm on a Saturday. There were restrictions on who could sell alcohol — road toll keepers, for instance, were no longer allowed to have this sideline.

What were the results of the Act? A review in 1858 quoted Lord Melgund as acknowledging that, while the sale of spirits had greatly declined, it was his belief that this was due to a considerable rise in duty on spirits.

The number of licensed premises in Glasgow had gone down from 1,900 to 1,600, though his lordship said this had led to a great increase in illicit trade.

On the other hand, Greenock advocate and British temperance societies founder John Dunlop argued that the Act had worked well. Cases of drunkenness in Glasgow had fallen from 71,648 in 1851-53 to 53,146 in 1854-56, a decrease of 18,502.

A letter to the Dumbarton Herald in January 1858 commented favourably on the effect of the Act on drinking in Helensburgh.

The 1853 Act was followed by the Methylated Spirits Act two years later, aimed at removing the temptation for drinkers to turn to this alternative form of alcohol.

Other measures were aimed at disrupting the illicit manufacture of alcohol, including greater police powers, and better resources for excise officers. Fiscal powers were used as well.

The net result was that by the later decades of the 19th century, places like Smugglers Glen no longer formed the habitual haunt of those operating “sma' stills”.

Statistics confirm that alcohol consumption did fall away significantly during the course of the 19th century — so it might be supposed that the movement would have gradually withered away, its purpose being redundant.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Despite some progress, countless lives continued to be ruined by the misuse of alcohol, with the need for action seemingly as great as ever.

Temperance in fact evolved and adapted over time to the extent that its core philosophy was taken aboard by many organisations and structures from the later Victorian period onwards.

What happened in the Helensburgh area was a microcosm of what was taking place nationally.

By 1844 the umbrella body was the Scottish Temperance League. As well as providing a central framework, the League operated locally through various local abstinence societies.

A Scottish Temperance League register of 1862 offers a fascinating glimpse into how this was organised.

In Helensburgh, the society president was the Rev James Troup of the Congregational Church, vice-president Thomas McEwan, mason, Sinclair Street, treasurer Colin Campbell, mason, Colquhoun Street, and secretary Andrew Provan, bookseller, Princes Street.

Names of other members are given as well, along with occupations, offering a useful insight into the sorts of townspeople who were involved. Perhaps surprisingly, these included several ladies — this at a time when female emancipation was still a distant dream.

In fact, all the local societies included lady members.

At Arrochar, the president was Robert Stewart, Inland Revenue officer; at Cardross, Major J.T.Geils; at Cove and Kilcreggan, which had more members than its counterpart at Helensburgh, James Roy; at Rosneath, William Clow, sawyer.

The League maintained a local presence until 1924, when after amalgamation with another organisation, the name was changed to the Scottish Temperance Alliance, and under that banner, it was still functioning at the outbreak of World War Two.

In 1939, the Helensburgh Council, as it was termed, had as president the Rev W.D.Bruce of the Congregational Church. By 1956 the Temperance Movement a more or less spent force.

Another significant temperance initiative was the British Women's Temperance Association. It was founded in 1876 and there was an Edinburgh branch just two years later.

The basic aim was to stop men drinking. It called for total abstinence, and it was influenced by the Gospel. Women had no political voice, yet where alcohol abuse is concerned, it was undoubtedly women and the children who were usually the first to suffer.

The author Elspeth King quoted from a report from a Glasgow missionary worker: “Saw in several houses the effects of intoxication.

“In one house, found a man almost in a state of insanity by ardent spirits. His wife, quite a young woman, was sitting crying, and the blood flowing copiously from a wound, inflicted by him on one of her eyes.

“In another house, met with a woman intoxicated. In a third, found a man in a beastly state of intoxication — all cut in the face, caused by falls. In a fourth, a woman sitting crying.” Similarly, another worker reported: “Out of the 12 families I visited today, not more than one woman was at peace with her husband. The men are all drunkards, and they abuse their poor wives when under the influence of strong drink.

“These poor decent women said they could not live with their husbands; that rather than be murdered by them, they were thinking of separating from them, even though they should have to beg their own and their children’s bread.”

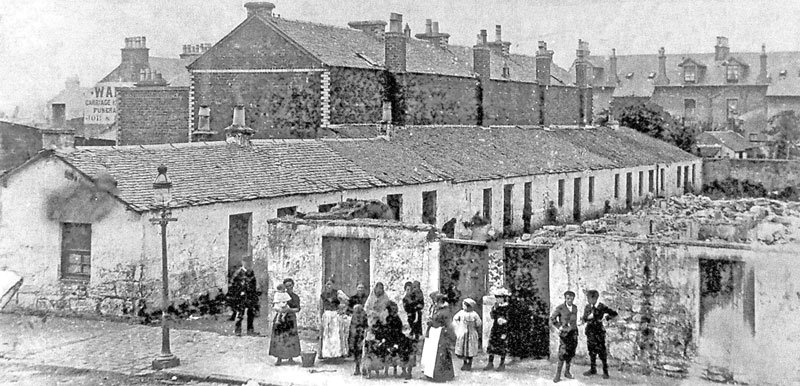

Such horrors were not confined to the big city. Places like ‘The Barracks’ (top picture), in Helensburgh’s James Street, witnessed some sad and sordid scenes, and doubtless various other places as well.

A branch of the BWTA was in existence in Helensburgh by 1907, which does seem quite late, but local women did at least have a voice through the Scottish Temperance League.

However, having a body that focussed heavily on women and the family must have meant that their priorities would have exerted real influence on the local debate.

Annual meetings were held at the Victoria Hall, and there was a significant membership base — in 1929, when the president was Mrs R.G. Service, local membership stood at 500. There was also a juvenile section, known as the ‘Little White Ribboners’.

When voting took place twice in the 1920s on the matter of whether or not Helensburgh should become a “dry” town, it might be expected that the BWTA would have been extremely pro-active.

It certainly was active, locally and nationally, in 1916, when Parliament was being petitioned to prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcoholic liquor.

Under the terms of the Licensing (Scotland) Act, 1913, communities were first empowered in 1920 to vote on whether they wished to remain as they were, seek to restrict licensing, or even make their area free from the sale of alcohol — the so-called “Veto Poll”.

Some 584 communities stepped forward, having surmounted the first hurdle, which required that 10% of the electorate sign a requisition asking for the opportunity to vote on the matter. For the first time, women were able to take participate, provided they were over 30 and met basic property requirements.

In October 1920, Helensburgh voters presented the town council with a requisition for a vote be held. With a registered electorate of 4,309, voting was: votes cast 2,941; votes for “No Licence” 1,332; votes for “Limiting Licenses” 109; votes for “No Change” 1,500. The status quo was thus maintained.

Elsewhere, only around 40 communities were successful. Typically, these were small towns like Kilsyth, Kirkintilloch and Lerwick, along with middle-class city areas like Kelvinside and Pollockshaws.

Another vote was carried out in Helensburgh in 1923, but again the result was “No Change”. For any vote for change to be valid, 35% of those on the electoral roll had to vote, and for local prohibition, there had to be a majority of 55%.

On the outbreak of World War Two, the president of the Helensburgh branch of the BWTA was Miss McMillan of Rhu, secretary Mrs Robert Leary, West Princes Street, treasurer Mrs Orr, William Street, and superintendent was Mrs William Wilson.

However, as in the case of the Scottish Temperance Alliance, a town directory of 1956 makes no mention of the BWTA, and the local branch can be assumed to have folded.

The ladies of Helensburgh and District very much supported the growth of the Temperance Movement, and perhaps the most ardent were those who were members of the Band of Hope (some of whom are pictured above at a garden party and conference held at Cairndhu House on Helensburgh seafront on June 6 1908).

They fully subscribed to the growing awareness that society was being blighted by a culture of excessive drinking, and that action was desperately needed.

Many churches and evangelical groups became involved in the field of temperance, with the Band of Hope leading the way.

The idea behind trying to dissuade children from taking alcohol goes back to Leeds in 1847. In that year, the Rev Jabez Tunnicliffe, a young Baptist minister, was deeply affected when a dying alcoholic clutched him and begged him to turn young children away from strong drink.

The problem of children becoming alcoholics went back for centuries. The Band of Hope was the outcome.

In 1871, the Scottish Band of Hope Union was formed in Glasgow to co-ordinate the efforts of the many individual branches that had come into being. The first chairman of the Union was William Quarrier of Quarrier's Homes fame.

However the Band of Hope appear to have taken some time to become well established locally.

A Cove and Kilcreggan Band of Hope was formed in 1882, but at Garelochhead it was not until 1890 that a Band was established, under the supervision of the Rev Walter Ireland of the Free Church, with 77 youngsters attending.

In Helensburgh, the Free Church — which became the United Free after 1900 — was the church most prominently involved.

In 1939, Park Church, formerly a Free Church, had a Band of Hope running under a superintendent, William Cook. The children met on Friday evenings.

Mainstream churches were not the only bodies have branches of the Band of Hope. Evangelical organisations were also frequently involved.

One such organisation in Helensburgh was the Town Mission. This was started up around 1875 by a group of young men and women, whose perception was that there were large numbers of children in the town either neglected or overlooked by the churches.

The Town Mission had the aim of bringing together those children on Sunday mornings in a Christian environment. They met in the Mission Hall, for many years located at West King Street.

According to the author of ‘The Story of Helensburgh’ — published anonymously, but generally accepted as being the work of long-serving town clerk George MacLachlan — around 400 children gathered together in the Mission Hall on Sundays for prayers, hymns and Bible readings.

At the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, the Band of Hope movement had almost three million members across the whole country, but in common with so much of the Temperance Movement, numbers attending had shrunk dramatically by the 1950s.

Writer Elspeth King stated: “Most people who had experience of Band of Hope meetings in the inter-war years remember them only with fondness and nostalgia.”

The Band of Hope proved to be something of a survivor. In 1994, the name was changed to that of Hope UK, and the organisation now works internationally, fighting drug misuse, and helping to meet old and new health challenges faced by young people.

The Roman Catholic Church had its own temperance organisation, the League of the Cross. Founded by Cardinal Manning in 1873, this offered a philosophy of total abstinence.

Open to clergy as well as the laity, it had a presence in Helensburgh from about 1905, and met in the League of the Cross Hall, Grant Street, on Sunday evenings. As with many temperance institutions, there was a pledge to be taken.

In 1939, the president was John Friel, vice-president F.Tierney, treasurer the Rev Simon Keane, and secretary William Emerson.

Once again, as with so many strands of the Temperance Movement, the League of the Cross appears to have ended by the post-war years.

Also involved was the Salvation Army. Its roots can be traced back to London in 1865, when William Booth founded his embryonic organisation.

It was not until 1878 that the Salvation Army took on the character by which it has become famous, with ministers becoming known as officers, and carrying various ranks, as in the Regular Army, and having uniforms. It was then that William Booth became General Booth.

With regard to temperance, right from the very beginning there was heavy emphasis on the avoidance of alcohol. Officers had become aware that misuse of alcoholic drink lay at the very heart of many of the problems they encountered in the field.

The first branches in Scotland appeared in 1879. There was a Salvation Army presence in Helensburgh by the 1890s, which was to last until at least the mid-1950s.

For many years, the Salvation Army barracks were at Rossdhu Place, West Princes Street, while officers were based at 27 West Princes Street. Later the barracks moved to 25 East King Street.

Some branches ran a Band of Hope, although no information has been found about them running one in Helensburgh. One feature of the local corps, as elsewhere, was the Salvation Army band, which must have served to help raise the spirits on so many occasions.

The local branch received a tremendous boost in October 1910, when General Booth, who was 81 at the time, visited the town, arriving at Craigendoran by train.

The General addressed a crowded Victoria Hall that evening, when he spoke for an hour and a half.

He left by steamer from Helensburgh pier the next day (pictured above), bound for Port Glasgow, and was seen off by town and county dignitaries. He died just two years later.

By the mid-1960s, there was still a corps in the town, but ultimately yet another familiar institution closed its doors.

In recent years the Salvation Army returned to Helensburgh, where it runs a charity shop. In a sense, it is entirely appropriate that this should be located in West Princes Street, very close to where the corps once conducted its business.

A number of friendly societies had temperance at the heart of their philosophy. They were mostly formed in the 19th century, and members paid a modest annual fee, with the organisation providing them with help and support as the need arose.

Essentially, membership served as an insurance policy, providing a buffer against life’s events like illness, injury, and unemployment, at a time when there was nothing akin to National Insurance or free medical care.

Given that some friendly societies were strongly anti-drink, it was ironic that meetings were generally held in pubs, certainly in the early days, but on the other hand, it underlines that few other suitable venues were available.

A good example of a friendly society that placed strong emphasis on temperance is the Independent Order of Rechabites. The name came from the Biblical Rechab, whose son Jonadab commanded their tribe to “drink no wine”.

The Independent Order was formed at Salford in 1835. It had a strong Christian base, and it was always eager to promote total abstinence. Its motto was “Peace and Plenty the Reward of Temperance”.

A Helensburgh presence began in the early 1880s but lasted less than a decade. Branches were known as ‘Tents’, an echo of the ancient Israelites. Each Tent was led by a Chief Ruler, supported by a Tent Steward, Inside and Outside Guardians, a ‘Levite of the Tent’, and the more familiar treasurer and secretary.

A remarkable feature of the Rechabites was their regalia. With full colour silk and satin sashes, aprons, ribbons and banners, they were reckoned to be visually the most impressive temperance organisation when they took to the streets.

As a result they were often given pride of place at temperance rallies, as at the great West of Scotland teetotal procession to Glasgow Green in 1841.

One attraction to join the Rechabites was that the whole family was encouraged to become involved. Indeed, they provided a model for friendly societies generally, being notable for their comradeship, good sick and funeral payments, and a well-organised provision for female and juvenile members.

Another friendly society which placed strong emphasis on temperance was the Independent Order of Good Templars.

The Order took its name from the Knights Templar of old, citing an old legend which claimed: “They drank sour milk and fought a great crusade against the terrible vice of alcohol”.

It based its structure on Freemasonry, using similar rituals and regalia.

Imported to Scotland from the United States by a Scot in 1869, the Order had 91 lodges in existence within a year.

As with the Rechabites, women were encouraged to join as full members. The constitution mentioned that alcohol avoidance would lead to liberation of the peoples of the world, leading to a richer, freer, and more rewarding life.

According to ‘The Story of Helensburgh’, the first Good Templars lodge was formed in the town in 1870 as the Henry Bell Lodge, which by the mid 1890s had 70 members. The Ardencaple Lodge, created in 1874, had 106 members.

The author commented: “Good Templarism, though eminently successful elsewhere, does not seem to have caught on here as it might, though total abstinence principles have widely diffused themselves, and are widely supported.”

By the end of the 1880s, in addition to the Henry Bell and Ardencaple Lodges, there was a Young Hope Juvenile Lodge.

In the 1870s, the Good Templars met at the Temperance Hall at 5 Maitland Street, but by the 1880s, the hall was located at 17 East Princes Street, and was used by both the Good Templars and the Town Mission as well.

In the following decade, the address is given as 24 West Princes Street, but it must be remembered that the east-west split changed around that time from Colquhoun Street to Sinclair Street, so the premises themselves may not have moved.

In 1906, the name of the organisation changed to the International Order of Good Templars, reflecting a more cosmopolitan stance.

The Helensburgh presence continued as before, but by 1928 there is no mention of it in local directories. Nationally and internationally, however, the Order continued its work.

There was a further change of name in 2003, when the organisation was re-styled the International Organisation of Good Templars. It continues to this day, fighting not only against alcohol, but harmful drugs generally.

Another friendly society was the Sons of Temperance. The Order was founded in New York in 1842, and it was unequivocally prohibitionist and aimed to secure legislation to that effect.

In many respects, the aims and structure were similar to those of the Rechabites. There were complex rituals and distinctive regalia. There was a female wing, the Daughters of Temperance, and a juvenile one, the Cadets of Temperance.

There was a presence in Helensburgh before the turn of the 20th century. The official designation was: Sons of Temperance, Helensburgh Division, No. 864.

In the 1930s there was a change of name, following an international dispute, when the Grand Division of Scotland seceded from the parent body, altering its name to Sons of Scotland. The breach was later healed, but the changed name stuck.

By 1939, the designation in Helensburgh was: Sons of Scotland Temperance Society, Helensburgh Division, No. 864. The Financial Scribe was D.W.Morton, 28 East Clyde Street, and the treasurer was John Blair of Arden Cottage, 37A Charlotte Street. There was a Lily Cadet Section, the patron being Mr Morton.

Once again, this temperance organisation did not survive the post-war era.

Another movement which incorporated abstinence as part of its philosophy, and which definitely did play a big role in the area, is the Co-operative Movement.

There was always a strong element of social responsibility in the Movement, and this included the matter of alcohol.

The Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society was formed in 1868, and it was decided that there should be no association with any person or society that retailed alcohol. It was only in 1958 that this principle was set aside.

Today the Co-op maintains a strong presence in Helensburgh and elsewhere in the area. However, alcohol is readily available on the shelves.