THE SUMMER of 2019, with the much-loved paddle steamer Waverley out of action because of boiler problems, the Clyde off Helensburgh seemed quiet and a lot less fascinating.

But that was certainly not the case in 1949-50, when the then favourite Clyde steamer had extremely noisy jet engines.

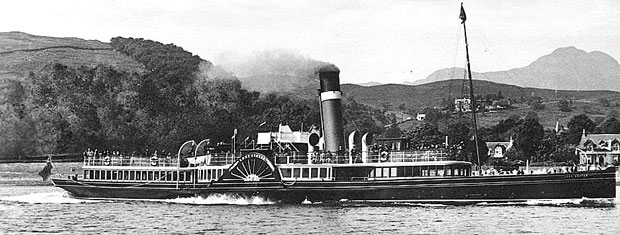

The 190-foot 271-ton Lucy Ashton was launched on May 24 1888 by Thomas B.Seath of Rutherglen at his Broomloan yard.

She began service on the Holy Loch run but later became more familiar on the Gareloch service from Craigendoran, and as the ferry across to Greenock.

She remained on the Clyde throughout both world wars, and she made her last run as a traditional vessel in February 1949.

At several points in her career she was on the brink of being sold off, but she was a survivor!

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 led to all the Craigendoran steamers with the exception of the Lucy Ashton being called up for minesweeping and anti-aircraft duties.

As a result she single-handedly provided the wartime service from Craigendoran to Gourock and Dunoon in summer and winter — travel beyond Dunoon was impossible because of the anti-submarine boom which stretched from Dunoon to the Cloch lighthouse.

In addition she served as a tender to some of the wartime troop ships lying off the Tail o’ the Bank.

The London and North Eastern Railway Company, owners of all the Craigendoran steamers since 1923, wanted to resume full passenger sailings as quickly as possible after the war ended.

However some of their vessels had been lost to enemy action, including the first Waverley at Dunkirk, and the vessels commandeered by the Royal Navy required alterations to make them suitable for a return to passenger service.

Because of this the Lucy Ashton continued in service for another four years. Many expected her to be sent to the shipbreaker’s yard in 1949, but that did not happen.

Instead she was purchased by the British Shipbuilding Research Association who wanted to do tests on different hull shapes, and to see what effect they had on the resistance to travel through the water, and hence also on speed.

The RSRA had already produced six wax hull models of the Lucy Ashton for use in the Denny Tank in Dumbarton, and her purchase enabled them to do comparative tests between the wax models and the full-size hull.

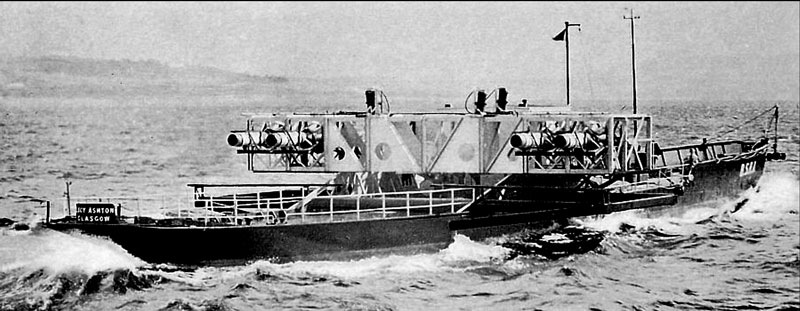

To carry out these tests the Lucy Ashlon’s paddle wheels, projecting protective sponsons, and engines were all removed, along with much of the decks.

Not much more than the basic hull and a bridge were left. A little aft of the bridge a structure was built across the hull, extending beyond it on either side.

To this were fitted four Rolls-Royce Derwent jet engines, and the former steamer underwent speed tests on the measured mile in the Gareloch.

The crew had to spend a considerable amount of time at the start of each test day calibrating the jet engines which could produce a speed of over 15 knots. There were many scientists on board, monitoring the tests with their instruments.

A crew member at the time from Helensburgh, Denny’s trained rigger Ian Gillies, told the Heritage Trust newsletter in 2008 that the noise was ear-splitting.

The crew were provided with ear protectors, but they could scarcely hear one another speak above the roar of the jet engines. Ian recalled that the noise was so great that it could even be heard in Dumbarton.

Fortunately for crew and people onshore these tests did not occur on a daily basis.

There were periods when the Lucy Ashton was towed to one of the various dry docks which existed on the Clyde at that time. At one point a smooth thin concrete skin was applied, and the vessel returned to the speed trials in the Gareloch.

Later the concrete skin was modified to mimic overlapping hull plates, and further tests were then carried out.

During this period the Lucy Ashton lay at a mooring buoy off Faslane, and the crew would travel there from Dumbarton on board the Second Snark which at that time belonged to Denny’s.

They used it principally as a tender and to tow barges between the shipyard and their engine works which were just beside the Dalreoch railway bridge.

“Have you ever heard of a ship with a handbrake?” Ian would ask people, and when the answer was in the negative, he replied “Well, the Lucy Ashton had one!”

Anyone who has watched the Waverley will have observed that the way to slow down or stop such a ship is to stop the paddle wheels, or perhaps even put them into reverse.

When the Lucy Ashton had her jet engines, the paddle wheels had been removed and in those days there was no reverse thrust for jet engines.

The only way to stop her was to devise a system similar to the stopping of the paddle wheels. This was the “handbrake”.

When the handbrake was released in the wheelhouse, two steel plates descended into the water, one on either side of the hull. This was the only-way of stopping the vessel when under jet power.

Many of the Lucy Ashton’s fans were sorry to see the old ship not allowed to go peacefully to the breaker’s yard after 61 years of service, but to be used for this undignified experiment instead.

One reason for their affection was that she was the last of the old-fashioned Victorian paddle steamers — for example, despite many alterations during her life, the bridge was a high platform located between the paddle boxes with the result that the view forward from the steering wheel was obscured by the funnel.

Others felt that it was good that the old ship could still make a contribution to science after so many years of service, and the BSRA produced a technical paper giving the results of the tests which was highly thought of worldwide by naval architects.

Whatever one’s feelings, the experiments with the jet engines ended after two years, and the Lucy Ashton was finabroken up at the Shipbreaking Industries yard at Faslane in December 1951.

An exhibition at Helensburgh Library in West King Street in February and March 2008 was dedicated to the vessel.

It was organised by Ian’s wife Marion, at that time vice-chairman of Helensburgh Community Council, and was inspired by the opening of the new Hermitage Academy building at Colgrain.

Marion remembered her own school days at Hermitage School, then in East Argyle Street, and among the memories flooding back was that when the Lucy Ashton was dismantled, the ship’s wheel was presented to the school as a memento of the steamer.

When that building was demolished and replaced on a site at Colgrain in the 1960s, the wheel was on show there, and in 2008 it joined staff and students in their new school.

Marion spent months putting together a collection of pictures, models and memorabilia charting the life of the paddle steamer.

One of the Waverley steamers, she took her name from a character in Sir Walter Scott’s novel, ‘The Bride of Lammermuir’, and provided a vital lifeline for rural communities before the days of buses and cars.

Marion recalled: “She used to bring the children to school. When they took her apart it was decided that the children at Hermitage School should be given a memento, so they gave us the ship’s wheel. I was there that day and I’ll always remember it.”

In the 1930s, the steamer was doing five round trips of the Gareloch each week day, calling at all piers including Garelochhead, Helensburgh, Rhu, Rosneath, Clynder, Shandon, Rahane and Mambeg.

She carried school children, passengers and general cargo from 7.25am to 7.50pm. Each June, the town’s children boarded the boat and sailed away for the Sunday School Wednesday picnic.

“On that day there was hardly a child left in Helensburgh,” Marion said. “There was often a race between the Sunday Schools to see who would reach the pier first.

“It was quite a day out whatever the weather. We always had a church hall booked somewhere in case it rained.”

On January 25, 1950, Captain McFarlane presented the wheel of the Lucy Ashton to Hermitage School:

He told the assembled pupils and staff: “To you pupils I would say, just steer as good a course throughout your lives as this wheel has helped Lucy Ashton to steer, and I’m sure you would have no regrets.”

Marion added: “She was a well-loved wee boat and I really enjoyed getting the exhibition together. She was the first Clyde paddle steamer to have a lady purser — up until then lady crew members were confined to catering duties.”