ONE of the most distinguished pilots of his generation was posted to RAF Helensburgh — the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment — in February 1943.

After winning the celebrated 1927 International Schneider Trophy seaplane air race for Britain in a Supermarine floatplane, Flight Lieutenant Sydney Norman Webster’s career in the Royal Air Force really took off.

He became a celebrity after winning in front of 200,000 spectators, with subsequent publicity in Pathe cinema news, newspapers, magazines and many public appearances.

So it was quite a contrast when he disappeared from the limelight on being posted to Garelochside.

He had been promoted to Group Captain and appointed commanding officer of the highly secret flying boat base used by the MAEE.

He arrived at Helensburgh during a busy time for the estyablishment, as staff were testing Barnes Wallis bouncing bombs and other new bombs, as well as carrying out flying boat trials.

A review by the new C.O. of the set up at Helensburgh was ordered to cope with pressures of the war effort.

Webster’s reputation went before him. The test pilots at Helensburgh had an affinity with their new commanding officer, who was ‘one of them’.

His sleek mono winged Supermarine racer had been designed for him by R.J. Mitchell, who later designed the Supermarine Spitfire.

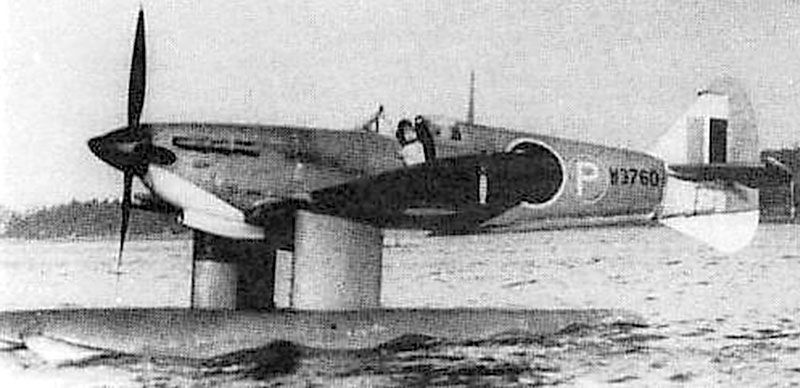

Webster (left) had hardly had time to settle in at the officers mess at Ardenvohr, Rhu, now the Royal Northern and Clyde Yacht Club, when a special delivery arrived by road — a prototype Spitfire floatplane W3760 for testing.

Webster (left) had hardly had time to settle in at the officers mess at Ardenvohr, Rhu, now the Royal Northern and Clyde Yacht Club, when a special delivery arrived by road — a prototype Spitfire floatplane W3760 for testing.

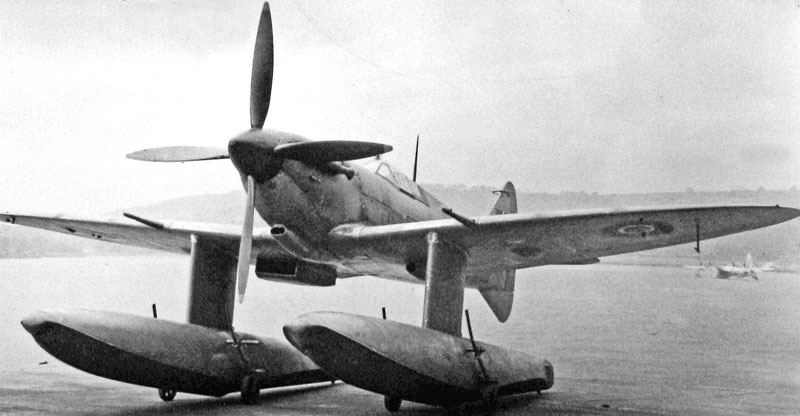

A world first in aviation, it was a converted Mk V Spitfire fitted with a pair of 25 feet floats and powered by a Merlin engine with a four bladed propeller.

Farnborough had been involved in a previous attempt at a Spitfire floatplane. It was fitted with Blackburn Roc floats which did not adapt well.

RAF Helensburgh was also experimenting at that time with Blackburn Rocs fitted with floats, but Blackburn Roc L3059 was so unstable that it crashed.

The first Spitfire floatplane project also handled badly. It was abandoned before attempting flight not just because of these problems but because Norway had fallen to the Germans, where it was to have operated.

Retired Merseyside newspaper editor Robin Bird, author of two books about MAEE, tells me that there was a story for many years that this Farnborough aircraft R6722 was taken by road to Blackburn, Dumbarton, to be fitted overnight with its Blackburn floats.

Then at dawn the completed Spitfire floatplane was loaded on the barge Dumborough and transported up the Gareloch to Helensburgh. But this is not true, Robin says.

R6722 was never transported to Helensburgh. It was converted back to a traditional fighter and crashed during the Battle of Britain.

The first Spitfire floatplane that flew was W3760, a converted Mk V Spitfire with a pair of floats 25 feet long designed by Arthur Shirvall, of Supermarine, who designed the floats for the Schneider Trophy racers.

W3760 was powered by Merlin engine driving a four bladed propeller. The aircraft looked good on floats and had previously been taken on a test spin from Southampton water when it attracted bursts of friendly ack ack fire.

For that reason it was taken by road to Helensburgh for safety reasons. Ironically Webster was not allowed to fly it because of a medical condition.

The trials were left to his test pilots. It would be something they had never experienced, a single seater Spitfire that took off and landed on water.

Robin has had exclusive access to pilots notes and logbooks at RAF Helensburgh. They show that Geoffrey Quill, chief test pilot of Vickers Supermarine, was first to fly Spitfire W3670 on Southampton Water shortly it was dismantled and taken to Helensburgh.

Here it was to be tested, its niggles sorted out and then the aircraft was to be handed over to the RAF.

Quill, probably the most experienced Spitfire pilot, travelled to Helensburgh to fly W3760 for the first time. He then instructed the MAEE test pilots.

One test pilot, D’Arcy Alexander Greig, had experience of a high-speed floatplane. Before the war while with the MAEE which was then at Felixstowe he was a member, with Webster, of the Schneider Trophy team.

Greig had flown a Supermarine seaplane racer at Calshot at 319 mph, said to be the fastest speed ever flown in any aircraft at the time.

Quill’s verdict after testing W3760 on the Gareloch was that all round performance was indistinguishable from a Spitfire, except for the top speed being less by 15 mph than the fighter.

After further trials W3760 underwent modifications and armament testing. Flight Lieutenant Desmond ‘Dizzy’ flew W3670 and recorded: “It was the most exciting aircraft. One thing you have to watch is the large amount of torque available from the Merlin engine. There could be swing on take-off but this could easily be handled.

“After all, the very much larger four engined Sunderland flying boat has a bit of swing too.”

Squadron Leader Percy Hatfield was posted to RAF Helensburgh after his Catalina helped spot the escaping German battleship Bismarck after sinking HMS Hood.

His posting to Helensburgh was seen by top brass as his reward, a break from operational duties. During his 14-month period as an MAEE test pilot Hatfield flew 16 different types of flying boats including the Spitfire floatplane.

No doubt Greig, Hatfield and Webster relived the Schneider victories over a drink in the officers mess. They noted that the Spitfire floatplane’s floats were fitted with rudders.

“Our Schneider aircraft did not and had to take off in a semi-circle,” observed Greig. who also advised Webster to warn test pilots that the Spitfire’s Merlin engine tended to overheat on taxying downwind.

Webster had only been at Helensburgh for a couple of months when Greig’s promotion to Air Commodore saw him posted elsewhere.

Aircraftman Lawrence Robertson found the Spitfire floatplane ‘scary’. His job was to moor and secure it to bollards on the Gareloch.

The floats protruded from the nose and he had to avoid the spinning four bladed propeller above his head before the engine was shut down.

After the teething problems with W3760 (right) were sorted, a report was prepared by James Hamilton of the MAEE which is now in the National Archives at Kew.

After the teething problems with W3760 (right) were sorted, a report was prepared by James Hamilton of the MAEE which is now in the National Archives at Kew.

Two more Spitfire floatplanes were completed, EP751 and EP754, and tested at Helensburgh. Along with W3760 they were signed off as airworthy by Webster for operational service.

Loaded aboard the SS Penrith they were shipped to Egypt ready to operate from small Greek islands against German transport aircraft. However, before this base could be used the islands fell to the Germans.

The aircraft were mothballed and later dismantled, a similar fate to the first Spitfire floatplane following the fall of Norway in 1940.

A further Spitfire floatplane MJ892 was made in 1944 for operations against the Japanese. This was the fastest Spitfire floatplane with a top speed of 377 mph, faster than a Hurricane fighter.

But the war against the Japanese ended before the floatplane could be used in action, and it too was dismantled.

Webster increased the manpower at Helensburgh which helped it cope with the growing workload, by then including the appraisal and testing of the Consolidated Coronado and Martin Mariner flying boats from America.

The Group Captain was succeeded during 1944 by Group Captain W.G.Abrams, who was in command until the end of the war.

Webster took command of an operational squadron, then became air officer commanding at Hong Kong. He retired in 1950 in the rank of Air Vice Marshall, and he died in 1984 aged 84.

RAF Helensburgh can not only claim to have had not only the first flying Spitfire floatplane, but all three.