MEMORIES of the night Cardross was bombed when she was ten years-old are still fresh for a villager who now lives in America.

Patricia Lockhart, now Mrs McInnis, left Scotland for Canada in 1956, and has lived in San Diego, California, since 1960.

She still has relatives in the village and elsewhere in Scotland with whom she keeps in touch.

They sent her the recent article which tried to address why a small village was attacked from above by the Luftwaffe over the night of May 5 1941.

The likeliest explanation involves a series of upland sites around built-up areas which were rigged up to fool would-be aerial attackers — and they were often successful.

Over 90 bombs were dropped on a site behind Maryland Farm, above Dumbarton, and which saved many lives.

There was a decoy site near Kipperoch, between Cardross and Renton, and this soaked up 205 bombs and six mines during the May raids.

Andrew Jeffrey, author of the book ‘This Time of Crisis’, is in no doubt that it was the proximity of Cardross to this site that led to the bombing of the village.

Cardross suffered three deaths and significant damage to property, a relatively high toll such a small place.

There was a heavy anti-aircraft battery at Cardross, one of a series built following the heavy bombing raids on Glasgow in 1941. It would have been armed with 3.7-inch or 4.5-inch guns.

But it could do little to protect villagers on the night of May 5, and it was a terrifying few hours for a ten year-old.

Patricia said: “We had a shelter my father had made from an old water tank the day war was declared. I think the shelter is still buried there.

“A lot of people laughed at him, but it was one of very few in the village at that time.

“We lived at Rosebank and there was an army camp just across the railway lines below us.

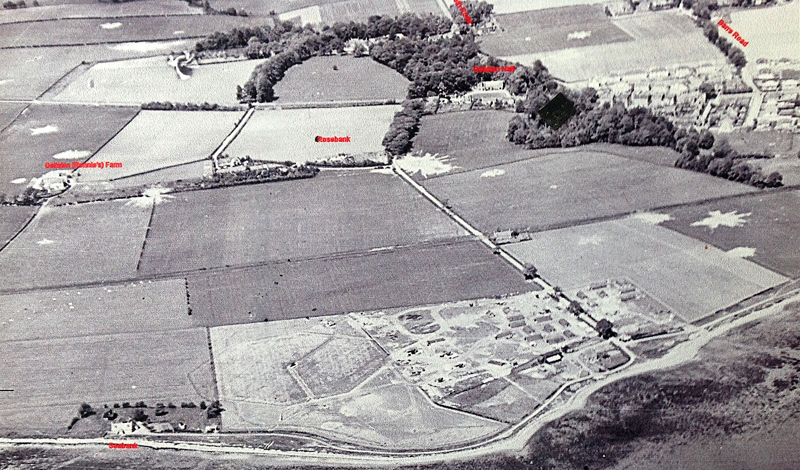

“There is an aerial view taken by the RAF the day after the raid that shows where the bombs fell. There was a huge crater just a few yards from our shelter — I remember feeling sick when I looked in it.

“Willie Denny of the Dumbarton shipyard firm lived across the road from us at Longbarn, and Mrs Denny was in our shelter.

“He stayed outside and doused the incendiary bombs that fell on our path. He was worried about his house as it had a thatched roof at that time.

“The shelter was very claustrophobic and as well as Mrs Denny, who sat at the door, her cook and her daughter were there — plus fourteen other people.

“Windows were blown in at Rosebank and shrapnel came through the roof. My aunt’s flat in Hope Terrace was completely destroyed by incendiary bombs.

“Our greenhouses were shattered. An unexploded bomb went off the next day at McIntyre’s Sawmill.

“I remember a little white cottage on the shore being destroyed. Two sisters lived there and they had a lovely garden, full of, if I remember correctly, lovely red geraniums.

“I thought only one person had died as a result of the bombing, because of a heart attack. It was erroneously reported that a Mr Lockhart had died, but as that was our family I know that was not true.

“There were quite a few nights when planes would come over and sirens would go off. We would run to the shelter. Of course we could see the fires and hear the bombs when Clydebank and Greenock were bombed.

“One of the reasons I left Scotland was because of the constant talk of wars. The Suez crisis was at this time and I did not want my children to experience a war.

“Ironically my son was of an age to go to Vietnam but fortunately got the right lottery number. I now have four great grandsons, one of whom is nearly eighteen — and the world is more dangerous than ever.”

According to the history of Cardross written by librarian Arthur F.Jones, the bombing alert sounded about midnight, and soon incendiaries and delayed action bombs began to have disastrous effects.

Several hundred craters were counted the following day.

The Old Parish Church and the Cardross Golf Club clubhouse — a two-storey mansion — were completely destroyed.

Also badly damaged were a cottage across the road; two cottages in Peel Street; Lady Denny’s Borrowfield House, where Bali Hi now stands; a cottage in Blairquhomrie Wood; the now rebuilt mansion Glenlee; two semi-detached villas on the main road near what is now the Co-op; Hope Terrace, a substantial two-storey block opposite the Geilston Hall; a cottage at the foot of Murray’s Road; Barrs Farm; and the Mollandhu Farm Steading and House.

Damaged to a lesser extent were Ardenvohr House, Cardross Mill, the railway footbridge at the east end of the station, and the Geilston Hall itself. Many other homes had ceilings caved in and windows broken.

Mr Jones wrote: “The fire-fighting efforts of the villagers during the worst period were tremendous, and only a limited amount of outside assistance was available.

“Those near the Parish Church were just getting ready to tackle the blaze when another high explosive bomb fell through the roof and destroyed the main part of the building.

“The bell was seen crashing to the ground and rolling to the doorway. The church records were fortunately saved.

“Other bombs fell on the churchyard and the manse grounds, shrapnel causing damage to many of the gravestones.

“Mercifully casualties were few. Only one person died on the spot, but one or two elderly people did not survive much longer, having received a great shock as a result of the calamity in general or of the damage to their homes in particular.

“Younger people worked hard in the ensuing months to repair damage.

“The Weirs at Kirkton Farm, who had suffered the loss of glasshouses, a boiler-house and various outbuildings, had within a year rebuilt the tomato houses and other buildings, cleared the debris, and filled in the surrounding craters.”

The Helensburgh and Gareloch Times reported the following Wednesday on ‘Two Night Attacks on Clydeside’, and referred to the magnificent work of the Defence Services.

It said that the official communique briefly stated: “On Clydeside the attack was heavy and much damage was done. There were a number of casualties.”

Sir Steven Bisland, District Commissioner, Civil Defence, said: “Once more the courage and self-sacrifice of the Civil Defence services during the raids have set a limit to the damage which could have been done.

“The phrase ‘the Civil Defence were magnficent’ is maybe well-worn, but it has indeed been well earned again.”

Although reference was made to a blazing village church and a farm fire, as was the wartime custom for morale reasons Cardross was not immediately named. That had to wait until the June 25 edition.

The report began: “The sleepy village of Cardross has had a curious fascination for Nazi airmen since the Battle of Britain began.

“Long before the destructive raids on Clydeside towns, a few high explosive bombs and some hundreds of incendiaries were dropped in and around the village on a summer night last year.

“The result of that early visitation was — damage, nil; casualties, nil; demoralising effect, nil; prestige, up 100%. The village proudly showed its battle scars — holes in fields and white patches left by burnt-out incendiary bombs.

“But when Greenock was an objective of the night raiders a few weeks ago, the ‘Port of Cardross’ — as the Nazis called the old-world hamlet — was also left battered and shaken by senseless and indiscriminate attacks on private dwellings, farms and a church.

“Except for a few private shelters and one or two communal shelters, the vast majority of the villagers had no protection against such an attack.

“Yet such is their pluck and endurance that they came through the ordeal more determined than ever to do all in their power to beat the Nazis and to save the world from such brutal aggression against defenceless civilians as they had experienced.”

The report said that there were few casualties, and only one of them fatal.

This was an elderly man who had shown remarkable coolness during the most intensive part of the raid and helped to extinguish incendiary bombs.

While extinguishing these incendiaries, he was killed instantly by the effects of a heavy high explosive type of bomb, one of the largest dropped.

The blast threw him to the back of a garage in which he was sheltering, and he was found dead by friends looking for him.

Wave after wave of Nazi planes followed in close succession as the raid developed, but there was also heavy anti-aircraft barrage and night fighters arrived.

“The defence was as strong as the attack, and the Nazis were forced into evading action which lessened the effectiveness of their bombing,” the paper reported.

A rest centre for the homeless was set up in the village hall, where members of the Women’s Voluntary Service made them comfortable until they could go to live with friends.

At the village golf course there were numerous unexpected hazards — huge bomb craters — and the clubhouse was destroyed. However a neighbour granted the use of his damaged villa as a temporary clubhouse.

The report added: “Members could console themselves at ‘19th hole’ on the loss of their clubs and on the unsporting action of the Nazis in damaging one of the finest courses in the west of Scotland.”