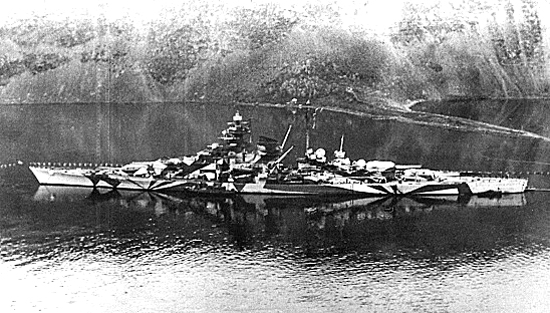

NOVEMBER 12 1944 saw the destruction of Nazi Germany’s largest weapon, the mighty battleship Tirpitz, at the end of a three year operation in which RAF Helensburgh was heavily involved.

Lancasters bombed the battleship, causing it to list and roll over, killing between 950 and 1,204 people aboard.

The historic event is well recorded, as are some of the previous attacks on the 42,900 ton Tirpitz as it lay hidden in Norwegian waters.

It became the target after the equally famous sinking of its sister ship, the 41,700 ton Bismarck which sank HMS Hood in 1941 then was immediately hunted down.

A pilot previously based at RAF Helensburgh had a role in spotting the Bismarck. He was Catalina pilot Dennis Briggs, who was then serving with 209 Squadron.

Then the priority was to find and sink the Tirpitz, and RAF Helensburgh took part in trials to work out how this could be done despite the target being well protected by mountains, poor weather and anti aircraft defence.

Highball bouncing bombs created by Barnes Wallis — better known for their use in the Dambusters raids — were used to ‘attack’ battleships moored in Loch Striven, with the ships and location representing the Tirpitz and Norway.

Mosquito pilots from the Helensburgh and Rhu-based Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment dropped the Highballs not only to hit their targets, but also to clear the nets that protected these vessels.

However this method of attacking the Tirpitz was not used in the end and was only one of a number of schemes considered.

Between 1941 and 1944 Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff were prepared to consider any scheme, however bizarre, that would sink the battleship.

One idea involved human chariots. The chariot torpedo was similar in size and shape to a conventional torpedo and could carry a 600lb detachable warhead.

Driven by two battery powered propellers it had a two man crew of frogmen, hence the name human torpedo.

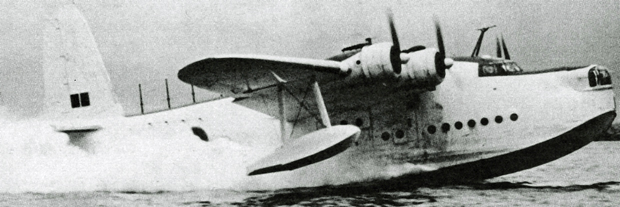

Ways of delivering the chariots by aircraft were investigated, and the most suitable and practical aircraft was the Short Sunderland.

Many modifications to the flying boats would have to be designed and made, which took considerable time.

Many modifications to the flying boats would have to be designed and made, which took considerable time.

It was not until July 1943, a year after the idea was mooted, that a very special, brand new Sunderland Mk111 flying boat, JM714G — G for ‘Guard at all times’ — was delivered to RAF Helensburgh.

This was one of five expensively factory modified Sunderlands, known as the Strike Force, which were to be used to attack the Tirpitz.

They were the trials aircraft JM714G (pictured top), JM715, JM716, JM717 and JM718 — all of which did not officially exist, or form part of any squadron.

Even at the secure base of RAF Helensburgh, Sunderland JM714G with its modified hull and strange external fittings was unusual compared to other Sunderland flying boats.

The Royal Navy charioteers joined the ranks of the MAEE.

In October 1942 a daring attempt to attack the Tirpitz using chariots, launched from a borrowed Norwegian fishing boat, failed through bad luck and heavy seas.

However, lessons were learned and it was then that the idea of using Sunderlands was progressed. The delivery of human torpedoes to the vicinity of the target by air was felt to have distinct possibilities.

On July 9 1943, Flight Lieutenant Harold Pipers, an MAEE test pilot, Sub Lieutenant Lee RN, an experienced charioteer, along with MAEE scientists and crew carried out the first handling tests with ‘dummy lumps’ fitted.

The Sunderland had minimal fuel and no weapons fitted, and handled well. Five days later the trials moved to the seclusion of Bowmore on the island of Islay where MAEE tested its most secret weapons.

JM714G had two chariots attached to its hull and they were successfully lowered from the aircraft with crews aboard.

Then, to make sure an operational Sunderland Mk 111 could take off with fuel, chariots and extra people aboard, the test aircraft was loaded with ballast taking it 10,000lbs over the normal permitted weight.

Despite this, take off was achieved after a run lasting 83 seconds over two miles. This meant that it should be possible to mount an attack on the Tirpitz in this way.

The aircraft could do it, and so could the crew of the aircraft and chariots.

Test runs took place at Helensburgh and Bowmore for two weeks with and without any objects fitted. MAEE people aboard included Mr Taylor and Flight Lieutenant Knight, according to Harold Pipers’ flying log.

But then the Chiefs of Staff had second thoughts.

The noise of Sunderlands approaching could alert the Tirpitz. How could the charioteers return to the Sunderlands and what if the flying boats had been attacked?

The final setback was news that the Tirpitz had moved to Altenfjord in the far north of Norway.

This location was more than 1,000 miles from the nearest possible base in Britain from where the Strike Force could be launched — and this was too far for the chariot-carrying Sunderlands to return home.

The mission was aborted. Instead JM714G was mothballed, along with the other expensively modified Sunderlands that then languished at Wig Bay, Stranraer, until the war ended.

The mission was aborted. Instead JM714G was mothballed, along with the other expensively modified Sunderlands that then languished at Wig Bay, Stranraer, until the war ended.

As a joint exercise between the MAEE and the Royal Navy, the trials of JM714G fitted with chariots was judged to be a success.

However, an invitation by Sub Lieutenant Lee to any of his new colleagues at Helensburgh to accompany him on a submerged chariot ride was politely declined!

Instead the Tirpitz was sunk near Tromso on November 12 1944, when the RAF carried out one of the war’s most successful precision bombing attacks, using 29 Lancasters of 9 and 617 Squadrons with Tall Boy bombs.