MEMBERS of the Helensburgh Naturalist and Antiquarian Society at the end of the 19th century would surely be absolute pillars of virtue.

But were they all? The so-called ‘Controversy on the Clyde’ in which they were involved is about forgeries, and remains a whodunnit to this day.

Archeologist and author Dr Alex Hale, who co-wrote ‘Controversy on the Clyde, Archaeologists, Fakes and Forgers: The Excavation of Dumbuck Crannog’ in 2005 for the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, tells the story, but does not point the finger of blame.

He believes that the crannog, an over-looked and undervalued site in the mud on the north shore, near Dumbarton Rock, has a hidden secret.

On the RCAHMS website he writes: “It’s not only the site itself, but also its recent history that is so fascinating. What appears as an innocuous pile in the foreshore mud belies a tale of controversy and mystery.

“This site is Scotland’s very own Piltdown Man forgery.”

The Piltdown Man hoax was a find of a skull from a village in Sussex, which was thought to be the ‘missing link’ between apes and early humans. The fragments were proven to be forgeries in 1953, and the perpetrators of the hoax were never discovered.

Dumbuck crannog gave up its secrets over 50 years before the Piltdown Man hoax was discovered.

The site was excavated in 1898 by a team of excavators from the august Helensburgh society, and a handful of artefacts recovered from the crannog were the cause for the ‘Controversy on the Clyde’.

During the excavations, apart from structural remains, a number of small, carved objects were recovered which had never been seen before and which were to give the archaeologists at the time and the archaeological institutions serious cause for concern.

The objects came to be known as the ‘queer things of the Clyde’. They were small pieces of stone, commonly known as ‘cannel coal’, which can be found on the shores of the Clyde.

Along with the cannel coal were a few shells, and all had been carved with both figurative and abstract designs.

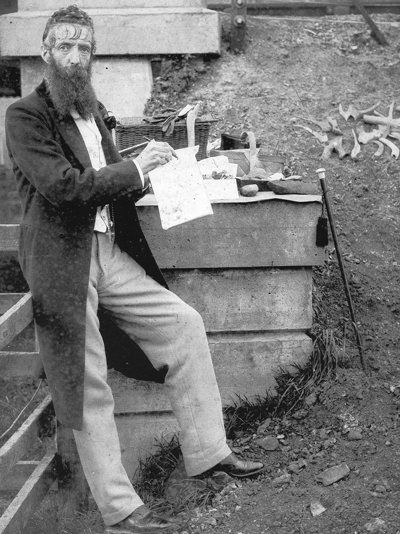

One of the men in charge of the excavations was William Donnelly (left), an artist from Old Kilpatrick, and during the summer and autumn of 1898 they waded out into the inter-tidal mud.

One of the men in charge of the excavations was William Donnelly (left), an artist from Old Kilpatrick, and during the summer and autumn of 1898 they waded out into the inter-tidal mud.

When the tide was down the excavators exposed parts of a 2,000 year-old prehistoric timber platform, surrounded by a stone and timber breakwater.

They also found that attached to the platform was a wooden-lined dock, within which they found a 40ft log canoe, which is preserved in the Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery in Glasgow.

The investigations and especially the ‘queer things’ generated a great deal of public interest and led to visits by delegations from learned societies of the time.

Donnelly recorded much of the excavations, the people involved and those who came to visit the crannog in sketches in his notebooks, and in the RCAHMS archive are glass lantern slides of his sketches.

Mr Hale writes: “These slides illustrate beautifully the crannog over 100 years ago and what life must have been like for the excavators on the shores of the Clyde.

“They show scenes of workmen trying to excavate the crannog as the inrushing tide fills their trenches.

“In one sketch Donnelly has drawn a family in full Victorian garb walking home from ‘doing the crannog’ carrying buckets and spades, and the mother carries a black parasol, shading her three children from the sun.”

In the book — available on amazon.co.uk — he and co-author Rob Sands trace the history of the site, describe the excavations, and argue why the ‘queer things’ deserve to be seen as Scotland’s very own Piltdown hoax.

After the artefacts turned up, the Helensburgh excavators quickly wound up the dig and the discussion began. Initially the words exchanged were complimentary.

But things soon degenerated, and private letters along with articles in the Glasgow Herald and the Evening Times started to be exchanged between those who excavated and various archaeological professionals.

Others got involved as the war of words became personal and the vitriol began to be penned.

It got to the stage whereby contributors assumed cryptic pseudonyms such as ‘XYZ’ and ‘High Water’, to avoid being identified, and it was certainly not what the society hoped for.

The 1899 Helensburgh Directory names the society honorary president as Sir James Colquhoun of Luss, the president as long-serving town clerk George Maclachlan — described in the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times as “genial and erudite” — and the vice-presidents as ex-Provost Alexander Whyte and ex-Bailie McCallum.

The secretary and treasurer was John Bruce, of Inverallan, 26 West Argyle Street, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquarians of Scotland and an expert on ancient local artefacts.

He was in charge of the excavations with another Fellow, Adam Millar, and William Donnelly.

Progress on the excavations was reported from time to time by the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times, and in the September 28 edition it was stated that stone implements of many kinds were dug up, including spear and arrow heads, hammers, scrapers and piercers.

To give members an opportunity of examining some of the objects, a special conversational meeting was held in the Reading Room of the Victoria Hall the previous Thursday evening, and there was a good turnout.

In the chair was William Turner, of Baranfrow, 68 Colquhoun Street, and Mr Donnelly gave a lengthy talk about both the work and the discoveries. Four days later members and friends visited the site to see for themselves.

The December 7 edition reported a further meeting chaired by Colonel R.Easton Aitken, at which a progress report prepared by Adam Millar was read by John Bruce (right).

The December 7 edition reported a further meeting chaired by Colonel R.Easton Aitken, at which a progress report prepared by Adam Millar was read by John Bruce (right).

It said that many people had visited the site, including members of the Glasgow Archaeological Society, the Glasgow Geological Society, the Glasgow Naturalists Society, and the Old Kilpatrick Naturalist and Antiquarian Society.

However there were sometimes unwelcome visitors on Sundays who vandalised the canoe and other parts of the site.

Dr David Murray of Cardross, considered one of the ablest of antiquarians, was asked to use his influence with the officials of the Clyde Trust to undertake the task of removing the canoe to a place of safety, which they did.

The owner of the site was a lady of the Geils family, Marchesa Chigi, who was married to an Italian nobleman. She was fully behind the venture.

As a result it was suggested that she should be elected an honorary member of the Helensburgh society, and both she and the Marquis of Lorne, soon to be Duke of Argyll, were given this honour.

The report stated: “The excavations, from the fact that the tide washed over the workings twice in 24 hours, were costing a good deal of money, but the committee hoped and expected that the society would provide the funds to carry this important investigation to a satisfactory result.

"Dr Murray was very much against the forgeries theory, and in a long article in the Glasgow Herald on March 22 1899 wrote that the ‘queer things’ had been denounced, but he could see no ground for that suggestion and regretted that it had been made.

He continued: “Those engaged in the work are above suspicion, and it is very discouraging to them and to other workers to be thus treated. The charge bears improbability on the face of it.

“It can hardly be conceived that anyone would take the time and trouble required to produce these objects, and on the assumption of forgery it has not been explained how they came to be buried deep in the undisturbed clay of the shore at Dumbuck.”

However today the objects are generally considered to be fakes planted at the time of excavation, and the perpetrator of the forgeries remains a mystery.

It does seem unlikely, however, that it was a member of the burgh society who either worked or helped to pay for the project.

William Donnelly died in 1905 and his son later stated that the controversy was one of the causes of his father’s early death. There have been at least two excavations at the crannog since then, and it remains preserved in the mud.

© The image of the crannog site is copyright Lairich Rig and licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Licence.