This article was written by well known Helensburgh artist and author Gregor Ian Smith for inclusion in a special Civic Week supplement in the Helensburgh Advertiser on May 9 1975 to mark the passing of the Town Council in the reform of local government in Scotland. Where necessary, up to date information is included in brackets in italics.

FOR a resident of over fifty years changes in the Burgh have been substantial. For those approaching the seventy mark, innovations and developments have been overwhelming.

I recall my mother telling us how her great grandparents had complained about the growth of Helensburgh. They were watching the process from their croft — now obliterated by Low’s Supermarket (now Tesco), and weren’t altogether happy with what they saw.

I also recall my own parents they picnicked in a field west of the Auction Sale Rooms (on East King Street opposite the Medical Centre) that reached to Argyle Street. That my mother’s parents lived in a cottage which was razed to the ground when the Goods Depot was created behind Helensburgh Station. Now the Goods Depot has been replaced by a car park!

I find myself watching similar things happening. I had a close look at recent reclamations beyond the Clyde Street car park — once crowned by the Breingan Band Stand — and found it a salutary experience.

For in this backwater we used to hire rowing boats by the hour from rival fleets owned by Mundies and McGettricks, and swam on New Year’s morning from the north steps of the pier, before competing in the annual ‘shoot’ in the Drill Hall in East Princes Street (now demolished).

I don’t suppose all changes are detrimental, but one way or another many have left us impoverished. We have long outgrown the image and status of a small, close-knit, rural community. The old ways have gone, and like the Round Seat on the Black Hill, are almost forgotten.

The late Duncan Mackay, whose upholstery establishment flourished in Clyde Street at the turn of the century, once told me that, as a boy, he and several contemporaries were pressed into accompanying the civic fathers on what amounted to a mini ‘riding-of-the-marches’, the annual inspection of the burgh boundary stones.

As each stone was reached, a boy was selected and soundly birched. Then for his pains — and they were considerable — the victim was rewarded with coin of the realm, the entire performance a sort of sweet and sour insurance that the location of the stones would be remembered . . . at least by the younger generation.

When one begins to make comparisons with the past and the present, memories come to the surface in sufficient numbers to fill more than the space allowed herein, and selection and economy must be exercised.

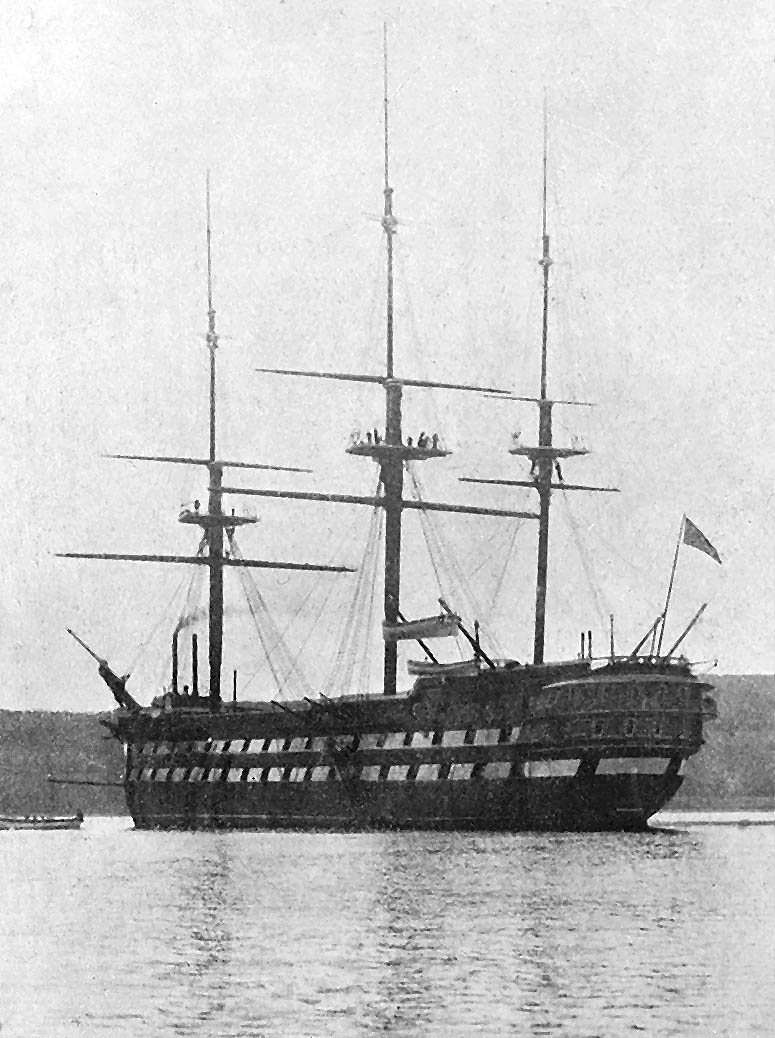

Starting with the postal services, there used to be four regular deliveries, two before midday and two before teatime. And I have beside me as I write, an old postcard featuring the ‘Empress’ (left), the resident training ship, riding a storm off Torwood Bay, Rhu.

Starting with the postal services, there used to be four regular deliveries, two before midday and two before teatime. And I have beside me as I write, an old postcard featuring the ‘Empress’ (left), the resident training ship, riding a storm off Torwood Bay, Rhu.

The stamp ensuring prompt and safe delivery cost a halfpenny! And the postman who delivered it was either Johnny Goodwin or Bob Maltman, wearing the cap of the period which by its shape brought its wearer nearer to the ranks of the French Foreign Legion than the Post Office!

Incidentally, I believe the first telephone exchange was established in East King Street in premises directly above Ian Walker’s electrical showroom (now the Life charity shop). I was taken there by an aunt employed as a supervisor where I learned later she and her staff occasionally let their hair down when a male caller attempted to date one of their number.

They conspired to set him up, persuading him to identify himself by a rose or flower in his buttonhole and wait at the corner of Sinclair Street for his chosen to appear. From the exchange window he was duly assessed by the group. If he looked presentable that date was kept. If otherwise — by majority vote — the budding romance, like the rose in his buttonhole, was allowed to wither.

Transport was simpler in the old days. You either swam, sailed, walked, used a bicycle . . . or took a cab. As a result, most of my memories are associated with transport by horse.

They pulled a variety of vehicles and came in all shapes and sizes. There are still a few of us around who are able to recall the departure of the mail from Helensburgh by coach-and-pair. And probably still more who remember the ubiquitous cab, and cabby complete in tile hat, claw-hammer coat and riding boots.

Cabs met all trains, often in association with badge-porters — a group of licensed luggage carriers whose headquarters were at the station. Cabs, broughams or landaus from Frews or Waldies stableyards conveyed us on urban and limited rural journies day or night.

Tales of cabs and cabbies varied from the sublime to the horrific. As youngsters we stole rides by sitting on the rear axles until the cabbies used their whips to dislodge all but the most foolhardy. And when a cab-horse was transferred temporarily to the shafts of the municipal watering cart, we followed it barefoot as the double-spray laid the summer dust.

But there was heavier spate of adrenalin when the fire brigade went into action. We waited breathlessly until the doors of the Sinclair Street fire station swung open and the team raced into action, rocking the gleaming fire-engine every bit as effectively as a Western stagecoach beset by desperados from the badlands!

In winter we were still literally rubbing shoulders with cabs. For when the snow fell we sledged down Sinclair Street, down Colquhoun Street, Charlotte Street, Grant Street, indeed any streets with enough snow to speed the ‘runners’.

Unfortunately cabs demanded fair share of the highway even in snow, and there are veterans in our midst who have sledged at high speed under the heaving belly of a cab-horse and lived to tell the tale.

Like the folks who lived on or ‘up the hill’, doctors had their private coaches and coachmen. One practitioner brought a touch of romance to his daily rounds when snow threatened to block the roads. He switched to a real Santa Claus sleigh, and his approach was heralded by the thud of muffled hooves, an occasional crack of the whip, and the jingle of sleigh bells.

A more macabre tale concerns another doctor whose practice extended to Rhu. His routine was to leave his machine and coachman near the entrance to what is now the Royal Northern (and Clyde) Yacht Club, and continue his rounds on foot.

According to legend it was dusk when he returned. A storm had blown up, and horse, coach and coachman had vanished. The mystery remains unsolved to this day, but it is assumed that the horse may have bolted and drowned with the coachman off gravel spit at the Narrows.

I believe in many ways we were better served in the old days. Perhaps I should use the word ‘pampered’.

Armies of errand-boys employed by local shopkeepers delivered their wares by bicycle throughout the town. Heavier deliveries went by horse-drawn vans. Fish-hawkers, fruit and vegetable merchants, and coalmen called their wares street by street.

Milk-floats announced their arrival by hand-bells, and we could identify each by its particular ’timbre’. Handcarts used by tradesmen to shift their impedimenta added their quota of sounds to the almost constant but curiously undisturbing background of noises.

Cattle grazed in fields like ‘Moss-end Park’, now covered with bungalows in South King Street. I have driven a dairy herd over Henry Bell Street bridge to be milked in Cameron’s Dairy between the railway line and East Princes Street. Courtrai Avenue marks the site of another farm and dairy, and Kirkmichael, Woodend and Milligs Farms have likewise disappeared from our ken.

Our recreational activities were largely of our own creation, like ‘tick-tack’, a game we played on dark nights with black thread, a hard button, and steady nerves; or ‘kick-the-can’, ‘release’, or ‘run-a-mile’.

But we patronised the cinema when it came to town. The first movie shows were presented in the Cine House, a corrugated-iron hall in John Street (later The Plaza Ballroom, now demolished and replaced by flats).

But we patronised the cinema when it came to town. The first movie shows were presented in the Cine House, a corrugated-iron hall in John Street (later The Plaza Ballroom, now demolished and replaced by flats).

The floor sloped steeply from the expensive back rows to the ‘neck-breakers’, orchestra enclosure, and silver screen.

On a Saturday matinee given over to Westerns, Mac Sennett comedies, serials like ‘The Diamond from the Sky’ and ‘The Clutching Hand’, youngsters unfortunate enough to be directed into the front seats lost no time when the lights dimmed in beginning the long journey on hands and knees under rows of occupied seats until they reached a safe haven, or were spotted by an attendant and ejected.

These were the ‘silent’ days, when the only sounds were provided by the resident orchestra, a hard-working quintet that could be relied upon to trace the development of any plot with suitable music.

Bells as well as horses occupied a great deal of our attention over half-a-century ago (circa 1920). The Parish Church bell was rung at six o’clock in the morning to rouse the artisans, and again in the evening to close the day — and the public houses!

On one occasion the bell ringer, a heavy drinker himself, was duped into ringing the bell an hour too soon, and was almost drowned in the Clyde by irate topers who had been done out of valuable drinking time by his stupidity.

Helensburgh may have been a small community but it was a lively one. By its support for cultural enterprises it earned for itself a high place in the list of towns fostering the arts, a reputation which was not altogether justified.

Subscription concerts and lectures by famous groups and personalities were well attended — at first. But a substantial number were there under false pretences, ready to fall asleep at the drop of a baton, forced into attendance by wives with social aspirations. Many such societies failed to stay the course.

There were, however, exceptions, hardy annuals still in existence, including the Swimming Club, Operatic Society and the Horticultural Society, although the annual flower show regrettably is a pale shadow of the grand occasion when international seed-houses, rose specialists, scores of dedicated gardeners, and a full scale orchestra combined to present one of the highlights of the year.

Another flourishing institution was the Highland Society, its numbers maintained by a regular influx of young women from the highlands and islands going into service locally.

With its close proximity to water, the youth of the burgh could always be relied upon to produce an excellent crop of swimmers. Another accomplishment was the skilful handling of boats, particularly yachts — which has missed me, for my roots are in soil rather than sea.

There was, however, one occasion when I was persuaded to accompany a school friend on what amounted to a voyage across the Clyde by rowing boat. He had surrendered to the charms of a redhead from Greenock, and reckoned that the cheapest, most direct and most romantic approach to Greenock was by rowing boat.

As the waves increased in size, so did the blisters on our hands. At one point we were surrounded by scores of porpoises apparently bent on capsizing our craft.

But the greatest threat was from river traffic which was heavy in these days, and in particular from a pugnacious tug preceding an ocean liner.

As the tug blew to warn us off we sat in horror as the liner’s towering, knife-edged bow bore down relentlessly. We survived disaster and a watery grave by about six boat-lengths.

Yet it was many months before I could forget the proximity of the liner’s gigantic propellors. Eventually we made landfall on Greenock’s foreshore where my friend departed, leaving me to look after the boat.

The wind continued to rise and the rain began to fall in quantities sufficient to justify Greenock’s astronomical rainfall figures. And when my friend returned, I was drenched, disgusted and ready to throw him overboard on the slightest pretext. However he was a determined lover and a glutton for punishment, and resolved to make a return journey the following week — alone.

In spite of a bad weather forecast, he set off. I remember waiting for him at the pier in the gathering dusk, reluctant to believe that a speck amongst the white horses of mid-channel was my friend. But it was, and he was being steadily blown down the Firth!

The upshot was an ignominious sea rescue by the angry boat owner in the wee sma’ hours, and the end of an adventure which I considered a bit of a waste of time, considering that he never did marry the girl.

I have had some doubt about presenting the foregoing for publication, as I acknowledge that they might justifiably be considered trivial and inconsequential. However they may serve to stimulate others with better and longer memories than mine to contribute further form and colour to a picture of Helensburgh’s not altogether inglorious past.