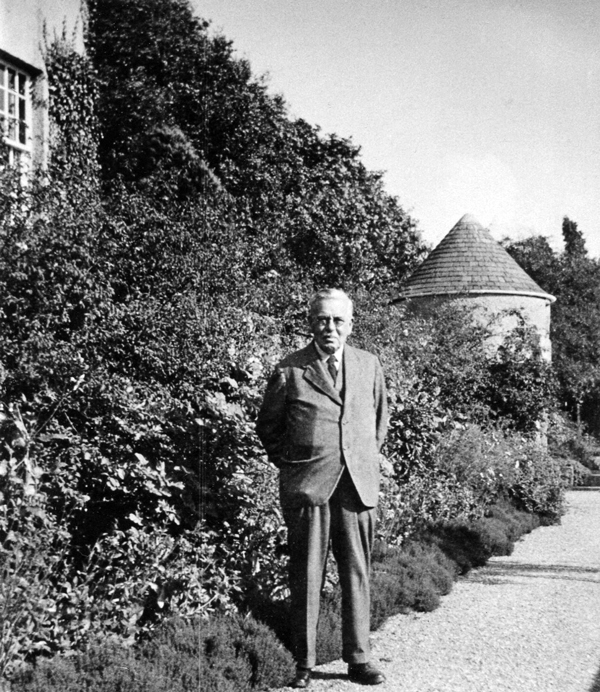

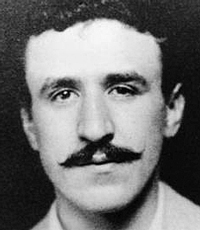

This article, believed to have been written by Walter W.Blackie about 1943, was originally published in the Scottish Art Review XI, No.4, 1968, by permission of Miss Agnes A.C.Blackie who found it among her father’s papers. It is published here by kind permission of two of the author's grand-daughters, Kathleen A.Salzberg and Ruth Currie, who kindly supplied the images from the family collection.

IN the early spring of 1902 my wife and I, having decided to leave Dunblane where we had lived for some seven years, were fortunate enough to happen on the site at the crown of the hill in Upper Helensburgh where ‘The Hill House’ now stands. We took the feu, and decided to build.

Fortune, again favourable, directed us to Charles Rennie Mackintosh for architect. Our approach to Mackintosh was on the advice of the late Talwin Morris, at that time Art Manager with Blackie & Son Limited.

The new School of Art was nearing completion. I had watched with interest its growth into the imposing structure that emerged, vaguely wondering who was architect, and when Morris named Mackintosh and recommended him as architect for my projected villa house I was at first taken aback, thinking that so distinguished a performer would be too big a man for me.

Morris, however, persisted in his recommendation and undertook to get Mackintosh to call upon me. He called next day.

When he entered my room I was astonished at the youthfulness of the distinguished architect. I myself was not terribly old forty years ago but here was a truly great man who, by comparison with myself, I esteemed to be ‘a mere boy’.

I soon found that the ‘mere boy’ was a thoroughly well-trained experienced architect, fully alive to the requirements of the villa dweller as to those of a school of art.

The conference did not last long. I put to Mackintosh such ideas as I had for my prospective dwelling; most negative, I may say.

I told him that I disliked red-tiled roofs in the West of Scotland with its frequent murky sky; did not want to have a construction of brick and plaster and wooden beams; that, on the whole, I rather fancied grey rough cast for the walls, and slate for the roof; and that any architectural effect sought should be secured by the massing of the parts rather than by adventitious ornamentation.

To all these sentiments Mackintosh at once agreed and suggested that I should see ‘Windyhill’, the house he had designed for Mr Davidson at Kilmacolm.

An appointment at ‘Windyhill’ was arranged, and my wife and I were shown over the house by Mrs Davidson, and left convinced that Mackintosh was the man for us. Thus we got started.

Mackintosh came to see us at Dunblane, to judge what manner of folk he was to cater for. I remember a strange happening just on his arrival.

In the small entrance hall there stood an oak wardrobe or cupboard we had purchased from Guthrie & Wells. Mackintosh immediately pounced on this wardrobe and said that he had designed it, explaining that, while still a student, he had designed sundry articles of furniture for ‘the trade’. It was a strange chance that we should have been the purchasers; a good omen, it seemed.

Before long he submitted his first designs for our new house, the inside only. Not until we had decided on the inside arrangements did he submit drawings of the elevation.

This first design was not approved. Thereupon, in a very few days, he sent us a new set of drawings which were accepted, and soon the first sod was cut for the foundations of ‘The Hill House’. The building was completed about the end of 1903, or early in 1904, and we entered into possession in March 1904.

Considerable delay in finishing the work arose from a prolonged strike at the Ballachulish slate quarries which were to provide the dark blue shade that Mackintosh had chosen for the roofs.

He would not accept any other slate then available, light or dark grey, greenish or purple. He would have none of these, the dark blue of Ballachulish being in his estimation the one and only utterly suitable for his purpose, in colour and texture. I am glad we had patience to wait.

He would not accept any other slate then available, light or dark grey, greenish or purple. He would have none of these, the dark blue of Ballachulish being in his estimation the one and only utterly suitable for his purpose, in colour and texture. I am glad we had patience to wait.

Mackintosh took a broad view of his architectural duties. Every details was seen to by him, practical and aesthetic. He provided cupboards where these would be useful, all fitted up to suit the practical requirements of the housekeeper.

The napery cupboard, for instance, well provided with trays and drawers, has the hot-water cistern hidden behind it to keep the linen warm and dry; the pantry also is well equipped with convenient drawers for cutlery etc., and presses with glass doors for china etc.

To the larder, kitchen, laundry etc. he gave minute attention to fit them for practical needs, and always pleasingly designed. With him the practical purpose came first. The pleasing design followed of itself, as it were.

Indeed it has seemed to me that the freshness or newness of Mackintosh’s productions sprang from his striving to serve the practical needs of the occupants, whether of a school of art, a dwelling house or a tea-shop, and give these pleasing decorative treatment.

Every detail, inside as well as outside, received his careful, I might say loving, attention: fire-places, grates, fenders, fire-irons; inside walls, treated with a touch of stencilled ornament delightfully designed and properly placed.

Early in 1904 Mackintosh handed over the house to us with these brief words: “Here is the house. It is not an Italian Villa, an English Mansion House, a Swiss Chalet, or a Scotch Castle. It is a Dwelling House.”

It is satisfactory to be able to report that when the final accounts came in for payment the total was rather under the amount of the original estimate, a tribute to Mackintosh’s competence in estimating.

The amount was indeed greater than I had originally meant to expend, and I had brought it down to my figure by cutting out many details which could be done without, though in themselves desirable, as, for instance, the terrace, the retaining walls of the feu, the specially designed wrought-iron gates and many other details.

But as the work progressed I got more and more in love with the discarded details and before we were done had restored practically all of them.

While the house as a whole bears the Mackintosh impress, four of the rooms — drawing-room, hall, library, and our own bedroom — had his special attention as decorator. Furniture and fittings, carpets and wall decorations were, in these rooms, practically entirely from designs of Mackintosh.

The gas fittings — there being no electric supply in Helensburgh at that time — were specially designed by Mackintosh, mostly in the form of lanterns and very beautiful. They have served for electric bulbs just as well as they did for gas.

He also gave us the main lines for the layout of the grounds; whereafter everything seemed to fall naturally into place.

I think it was in the late autumn of 1915 that I last saw Mackintosh. At any rate it was in the early days of the Great War.

I had received a brief note from Mrs Mackintosh asking me to call on her husband in his office. That was all — no reason assigned. It was always a pleasure to see Mr or Mrs Mackintosh so I called on receipt of the note.

I found Mackintosh sitting at his desk, evidently in a deeply depressed frame of mind. To my enquiry as to how he was keeping and what he was doing, he made no response. But presently he began to talk slowly and dolefully.

I found Mackintosh sitting at his desk, evidently in a deeply depressed frame of mind. To my enquiry as to how he was keeping and what he was doing, he made no response. But presently he began to talk slowly and dolefully.

He said how hard he found it to receive no general recognition; only a very few saw merit in his work and the many passed him by.

My comment, given without reflection, was that he could not expect to receive immediate general recognition being, as he was, born some centuries too late; that his place was among the 15th century lot with Leonardo and the others.

He rather gasped at this hasty appraisement, but presently began to speak clearly and collectedly.

He told me that his partnership in the architectural firm was now dissolved, and thought that, in itself, did not worry him. It so happened that certain plans for a public building which he had submitted, in name of the firm, had that very day been accepted in part and now he himself would have no superintendence of the construction which would be seen to by others who might not understand them.

He was leaving Glasgow, he told me, and so would not see his work materialise. Shortly after this he went to London and I never saw him again, though letters passed between us from time to time.

After the Great War Mackintosh and his wife went to live in Port Vendres in France, very close to the Spanish Riviera, where Mackintosh devoted himself to painting in water-colour. Those who know his pictures of the time will recognise in him a great water-colourist.

His importance as a painter was not long in receiving recognition from the management of the Tate Collection and he was encouraged to submit a picture for their consideration. The picture was duly submitted and accepted.

Under the rules of the Governors of the Tate Collection, as explained to me, there must be for any picture accepted, a donor other than the artist himself, and I was asked by Mr and Mrs Mackintosh to officiate as donor, a duty I gladly undertook.

I wished to buy the picture and so be actual donor and not merely pro forma, but the Mackintoshes would not have it so. So it comes that my name stands in the list as donor of a picture, entitled Fetges, I never possessed. It was finally received by the gallery in 1929, after the artist’s death in December 1928.

I wished to buy the picture and so be actual donor and not merely pro forma, but the Mackintoshes would not have it so. So it comes that my name stands in the list as donor of a picture, entitled Fetges, I never possessed. It was finally received by the gallery in 1929, after the artist’s death in December 1928.

I am glad to say that we possess some other Mackintoshes, including his delightful flower study of anemonies which was exhibited at the 1938 Glasgow Exhibition.

It was not very long after the Tate presentation that Mackintosh was stricken with the terrible complaint, cancer in the throat. After prolonged treatment, he underwent an operation and seemed to recover.

I got a letter from him to say how rejoiced he was to be well again; though the pain of the treatment and the operation had been terrible, now that he was restored to health and able to work, he was glad to have gone through with it.

The respite was brief. The illness recurred and Charles Rennie Mackintosh died. And so was cut short what was surely meant to be a great career.

During the planning and the building of ‘The Hill House’ I necessarily saw much of Mackintosh and could not but recognise, with wonder, his inexhaustible fertility in design and his astonishing powers of work.

Withal he was a man of much practical competence, satisfactory to deal with in every way, and of most likeable nature.

His death at almost the beginning of his career was a loss to all the world. Not many men of his calibre are born, and the pity is that when gone such men are irreplaceable.

When in my last talk with Mackintosh I happened to group him with Leonardo da Vinci, I spoke without serious consideration, no doubt. But on looking back, I feel that I may not have been far wrong.

Like Leonardo, Mackintosh, as it seemed to me, was capable of doing almost anything he had a mind to do. He might, for instance, have been a great engineer, as he was a great architect.

His water-colour pictures — an afterthought as it were — proclaim him a distinguished water-colourist just as Leonardo’s anatomical drawing — also an afterthought, and a recent discovery, I understand — rank Leonardo as a distinguished anatomist.

The credit for the first recognition in Glasgow of Mackintosh’s architectural genius belongs to the Directors of the Glasgow School of Art and to Fra Newberry, the Head of the School.

Whether this recognition succeeded or preceded the Turin success of the young Glasgow School of decorative artists I do not know, but it was to the Turin success that Mackintosh owed the wide recognition and acceptance he received in Germany, and, from Germany, in Holland and Sweden.

Germany had been adventuring new departures in architecture and decorative art and at once acclaimed Mackintosh as prophet of the new art.

Unfortunately the Germans were chiefly anxious to be new and, in absorbing what they could from Mackintosh, went wild in newness, not perceiving that the newness of Mackintosh was the outcome of his instinct to design for practical requirements and give these decorative expression.

That being his driving impulse he could not help being new in the result, however many hints or suggestions he might have received in the past.

There is, in fact, in ‘The Hill House’ a feature that he might be said to have ‘lifted’ from Traquair Castle. I noticed it only after we had been living in the house for years.

It is, namely, the two schoolroom windows that look down on the Court, on the north side of the house. They seem to me to have been inspired by windows in Traquair.

I am sure Mackintosh would have been glad that I had noticed the relationship.

His purpose was not to be new but to give fitting expression in design to a dwelling house of certain desired size, and meet the conditions of life of the occupants, and he could not help being new and fresh however many hints and suggestions he may have received from great works of the past.

As indicating the wide interest Germany took in Mackintosh, I may recall the publication, in 1905 I think, of a monthly number of the German art magazine Dekorative Kunst, almost entirely devoted to a full display of the features of ‘The Hill House’, external and internal.

Photographers were in the house for quite a while taking photographs for the magazine. It is surprising that the management thought there existed in Germany a sufficiently large body interested in Mackintosh to warrant this special issue.

Some years later there was a rather quaint repercussion. It came from South Africa where a certain professor, whose acquaintance I made later, was so much taken with Macintosh’s architecture as exhibited in Dekorative Kunst that he had a house constructed for himself as nearly as possible on the lines of ‘The Hill House’ though, as appeared later, he had no recollection of the name of that house of Mackintosh, only the features of it.

Some years later there was a rather quaint repercussion. It came from South Africa where a certain professor, whose acquaintance I made later, was so much taken with Macintosh’s architecture as exhibited in Dekorative Kunst that he had a house constructed for himself as nearly as possible on the lines of ‘The Hill House’ though, as appeared later, he had no recollection of the name of that house of Mackintosh, only the features of it.

After I had made his acquaintance, by chance I may say, I happened to ask him to visit us at ‘The Hill House’ when next he should be in this country. In due course he arrived, and, when I met him at the door, he exclaimed in astonishment: “Why, you have got my house.” Then he explained.

In the years before the Great War we had one or two calls from German architectural students with travelling scholarships who were enjoined to see the work of ‘The Great Mackintosh’. After that war and before this one we had occasional calls from architects and students of our own country, and the interest in his work seemed to be spreading.

Soon after Miss Cranston’s Sauchiehall Street tearoom was completed, Mackintosh was sought out by an American visitor and urged to transfer his activities to America where, he was assured, a fortune awaited him.

He turned down the proposal, his ambition being — as he explained to me or to someone who told me — to work for his native city of Glasgow. It is terribly sad that he should have died without fulfilment.

In a recently published supplementary volume to Dictionary of National Biography, in 1938 I think, there is a short biographical account of Mackintosh in which it is stated that Mackintosh and Robert Adam (1728-94) are the only two British architects whose work became known on the Continent of Europe. Note that both were Scotsmen.