A CHIEF Constable as a whodunnit suspect may sound rather unlikely, but a Helensburgh man who was Chief Constable of Dunbartonshire is named as a possible suspect in a modern book about an old mystery.

The book, entitled “Controversy on the Clyde: Archaeologists, Fakes and Forgers”, by Alex Hale and Rob Sands, published in 2005, tells the story of archaeological excavations conducted at Dumbuck Crannog, near Dumbarton, shortly before the turn of the twentieth century.

The dig unearthed genuine and ground-breaking finds, but also produced some strange objects unlike anything else previously discovered in this country.

This led to a lengthy and increasingly bitter controversy over the validity of the unusual objects found there and at several other sites.

The excavations were carried out under the auspices of Helensburgh Naturalist and Antiquarian Society, and the charge against the disputed objects was that they were fakes.

But who was the perpetrator? The strain caused by all the fuss is alleged to have played a big part in the untimely death of the chief excavator, the artist William Donnelly.

The chief constable was Charles McHardy (above left), and he found himself in the unlikely position of being a named suspect in the surreptitious planting of false artefacts.

Charles McHardy came from a distinguished line of Braemar highlanders. His branch of the McHardys was known as the “Buie McHardys” because they hailed from Ballochbuie Forest on Deeside.

Men from there were famed for their size and strength — any under six feet were considered small.

Charles’s father, William, served for many years as head keeper on the Earl of Fife’s Mar Estate, and excelled in heavy events at Braemar Highland Gatherings.

Wearing full highland dress, William cut a fine figure of a man, and had his portrait painted by command of Queen Victoria, having been one of those chosen to form part of the escort when Her Majesty and the Prince Consort first visited Scotland.

Young Charles began working life as a ghillie, but the lure of public service saw him moving south in 1863 at the age of 19, when he joined the police force in Dunbartonshire.

His first appointment saw him serve in an area stretching from Bowling to Whiteinch. His high character and ability soon marked him out for promotion, and after a posting to Kilcreggan, he moved to Alexandria as sergeant in 1872.

Two years later, he became an inspector, and four years after that there was a further step up to superintendent in command of the police force at Helensburgh where he also served as burgh prosecutor and sanitary inspector.

Further promotion came with his appointment as chief constable of Dunbartonshire Constabulary in 1884, a post he was to occupy until his death in 1914.

Two of his brothers also attained senior rank in the police service. One, Alistair, rose to become chief constable of Sutherlandshire and then Inverness-shire. Another, William, became an inspector with Aberdeenshire Constabulary.

In his professional capacity, Charles was noted as a strict disciplinarian but he was very popular with rank and file colleagues, while managing to gain the respect of the public at large.

He always stressed the need for fellow officers to set a good example to others, and he was very kind at times of illness or bereavement.

In 1901, as a token of their respect, his colleagues presented him with an illuminated address and a fine oil painting of Charles and his wife.

Charles served on several occasions as president of the Chief Constables’ Club for Scotland, and gave evidence before several Royal Commissions.

He was particularly alert and well-informed on licensing matters, and in several instances gave striking evidence on the evils of raw-grained whisky among the working classes.

His firm view was that no liquor should be sold unless it had matured for the statutory period in bond. In his later career, he became the proud recipient of the King’s Police Medal.

He had an imposing presence, especially on horseback, and was a feature at many important county functions.

Under his direction, the county force vastly improved its effectiveness and its strength. When he first joined, there were 20 officers, but by the time of his death, the total had risen to over 120.

Forward-looking, he quickly realised the vital role that the telephone could play in the fight against crime, and his priority was to have a phone available at every police station.

It proved a hard struggle to achieve his ambition, but soon after, he was able to offer convincing proof of the power of the phone.

A man had been assaulted at Clydebank and left dying. The suspect had fled the scene, but the local inspector was able to phone Charles at midnight at his then Dumbarton home and report the details of what had happened. Within ten minutes of Charles receiving the call, the suspect was apprehended.

Away from work, Charles had many interests, especially in sport. Like his father, uncle, and many of his brothers, in his younger days he excelled in the heavy events held at highland gatherings.

His proud claim was to have beaten the legendary heavy events athlete Donald Dinnie in the caber throwing contest at Braemar Games in 1864.

A member of Braemar Highland Society, Charles also became president of Dumbarton Highland Society.

When he and his wife moved to Helensburgh in the late 1880’s and set up home at Millglen, East Argyle Street, he became an enthusiastic supporter of Helensburgh Highland Games, and was greatly saddened when these ended.

He also served as president of the Helensburgh and Clan Colquhoun Highland Association.

Another sport that greatly interested Charles was golf. He is credited with having practically introduced golf to Dumbarton, and along with the Denny brothers, was a founder member of Dumbarton Golf Club.

Established in 1888, the club was the oldest in West Dunbartonshire, and at its inaugural meeting, Charles was appointed the first Captain. He was also noted as a bowler, and served as president of Dumbarton Bowling Club.

The picture of Charles that emerges is one of a dedicated career policeman, who also enjoyed a wide range of recreational pursuits and was a solid family man.

So how did he end up as a whodunnit suspect?

Yet another of his interests was antiquarian studies, which is why he joined Helensburgh Naturalist and Antiquarian Society.

It is not known how active a member he was, but given his professional duties and his many other interests, it is doubtful if he would have had the time to become heavily involved.

His association with the Dumbuck dig arose through problems there with souvenir hunters — he undertook to arrange security to guard against unauthorised access.

He would thus have had the opportunity at Dumbuck to plant false objects, but doing this would not be as simple as it might appear.

He would have to have been aware of digs planned or in progress. Some degree of skill would have been needed to insinuate objects within ground deposits in such a way as not to excite the suspicions of excavators.

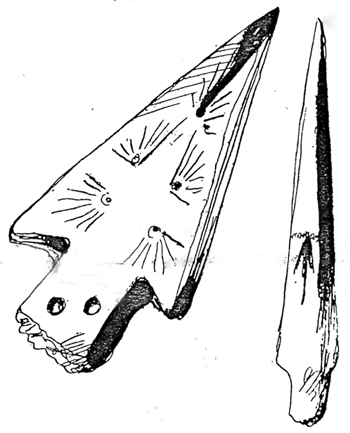

Some of the disputed objects were carved in cannel coal, a medium which was used for this purpose by prehistoric people. Would he have been aware of this?

While the carvings were described as crude, a certain amount of basic craftsmanship would still have been required, and therein lies the key to the inclusion of Charles as a suspect.

From an early age, he had developed the skills of carving walking-sticks as a hobby. He became very skilled in working with wood, horn and ivory.

Even Queen Victoria was made aware of his outstanding proficiency, and in gratitude for being presented with examples of his walking-stick craftsmanship, presented him with a copy of a fine painting of his father which hung in Balmoral Castle.

Edward, Prince of Wales, also became the proud possessor of several sticks carved by Charles, while his sister Princess Louise — who spent much of her later life at Rosneath — was gifted a pair of earrings in chaste ivory.

Charles therefore possessed the skills to produce the false artefacts (two are pictured right), but given his background and character, placing him among the suspects on these grounds would seem to be a very long shot indeed.

Charles therefore possessed the skills to produce the false artefacts (two are pictured right), but given his background and character, placing him among the suspects on these grounds would seem to be a very long shot indeed.

Authors Hale and Sands conclude that he was almost certainly above suspicion.

In early 1914, he was taken unwell. After he had an operation at St Elizabeth Nursing Home in Glasgow, complications set in, and he died on February 26 in his 70th year.

He was a devoted member of St Joseph’s Church in Helensburgh, and his funeral service was held there before interment at Helensburgh Cemetery. It was attended by many well-known people, including Sir Iain Colquhoun of Luss.