In this article specially written for the Helensburgh Heritage Trust website, Trust president Professor Malcolm Baird, son of TV pioneer John Logie Baird, recalls his childhood and student days.

LondonI WAS born on July 2 1935 at the family home at 3 Crescent Wood Road in Sydenham, a south eastern suburb of London.

A mile or so away was the historic Crystal Palace, built in 1851 for the Great Exhibition which marked the zenith of British industrialism. It had originally been set up in Hyde Park and it was later shifted piecemeal to Sydenham and reassembled.

From 1932 onwards, part of the Crystal palace housed the laboratories of Baird Television Ltd., until the building was destroyed in a disastrous fire in November 1936.

My father’s title in Baird Television Ltd. was managing director, but in 1932 the company was taken over by Gaumont British Pictures and he became only a token administrator. Nevertheless he received a salary of ₤4000 per year, this being about 20 times the average working wage.

He spent most of his time doing technical work on colour television at his small private laboratory, with his assistant Paul Reveley. The lab was located in the old coach house next to our home, so it might be said that I was born and raised in an atmosphere of science and technology.

However I have no recollection of the laboratory in those years. Access was strictly forbidden because of the high voltages, fragile cathode ray tubes and other hazards.

My time was mainly spent in the spacious garden which contained my main focus of activity, a sandpit; I was provided with a toy spade and a wheelbarrow. Through the calm air of that suburban garden I would hear the melodic strains of Chopin and Mendelssohn as my mother practiced on her Steinway grand piano.

Everything changed with the outbreak of World War Two in September 1939. British television was abruptly closed down and Baird Television Ltd. found itself with no market for its receivers. My father’s salary ceased abruptly.

Within hours of the declaration of war, the family moved to the small and remote town of Bude, on the windswept north coast of Cornwall.

Within hours of the declaration of war, the family moved to the small and remote town of Bude, on the windswept north coast of Cornwall.

After a few days in hotels and some short stays in various rented houses, we settled at Thymeland, 7 Flexbury Park Road, just across the road from the Bude golf course.

My father had an unshakeable faith in the value of his research on electronic colour and 3D television and he decided to continue it at his own expense. He worked on at the lab in Sydenham despite the bombing, and he would come down to Bude once or twice per month.

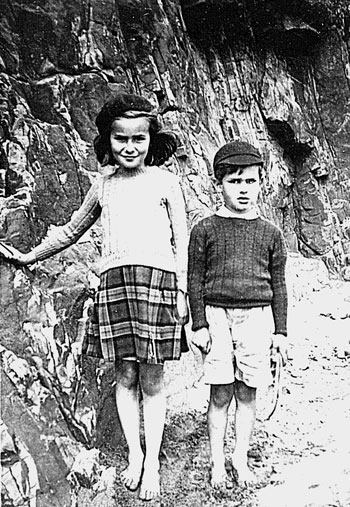

The family would hire a taxi for his arrival and we waited patiently at the station for his train, the 5.09, to appear in the distance. My father would emerge tired after the long and crowded journey, but he usually had small presents for Diana and me.

He would tell us stories that he made up as he went along. For example he told of two houseflies called Izzy and Dizzy who stayed in cold, draughty lodgings — perhaps a throwback to his early days of poverty before television came along.

He tried to instruct me in optics, and I recall the discovery that a piece of paper could be set on fire by focussing the sun’s rays on it with a lens.

If the weather permitted he would take Diana and me for a walk along the beach. He was a slow-moving figure, muffled in cap and greatcoat even in summer. From time to time he would stop and stare out to sea, deep in abstraction.

From my own limited point of view, World War Two was quite a happy time. My sister Diana and I attended a small family-run school called Sandown, within walking distance of our house, which took in boys and girls between the ages of 5 and 12.

The only bad part of my school experience was the food, including stringy roast beef and smelly cabbage. The teaching was good despite the fact that no-one on the Sandown staff had a university degree.

The headmaster, Stanley Sulman, was known as “Sir”. He was an imposing bearded figure who had served in the Boer War of 1899-1902. There was no science teaching and my interest in science came from my father.

Latin and French were well taught and I recall Mr Sulman reading us short stories by Guy de Maupassant, such as “Vendetta”. I re-read this recently and it seems to have been pretty powerful stuff for ten-year-olds, but perhaps Mr Sulman used an abridged version. As he went along, he quizzed us about what the words meant.

My most vivid recollections are of the enthusiastic teaching of English, History and Geography by Mary Radmore, Mr Sulman’s sister-in-law. There was a war on and everything was suffused with a patriotic flavour, oriented more towards England than Britain as a whole.

I remember Miss Radmore’s readings of the poems of Sir Henry Newbolt, such as Drake’s Drum and Admirals All. There was music, on records and singing to piano accompaniment.

Even now, on hearing Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance Marches, I have a momentary vision of the windswept Cornish cliffs and the enormous waves breaking on the rocks. Again, patriotism was well to the fore and we spent much time on a splendid old song entitled “The Fishermen of England”, now almost forgotten.

While I had a good early schooling, the war was a struggle for my parents. My mother had been used to an affluent pre-war lifestyle with a staff of servants in the big house at Sydenham, but now she had to make do with wartime rationing and shortages.

While I had a good early schooling, the war was a struggle for my parents. My mother had been used to an affluent pre-war lifestyle with a staff of servants in the big house at Sydenham, but now she had to make do with wartime rationing and shortages.

My father continued to carry a punishing workload in London, combining private research and some government work amid the air raids.

At the end of the war, the family moved to Bexhill, in Sussex. My father’s health had been weakened by his war work, but he carried on in London throughout 1945.

In October of that year the family came up to see the progress at his lab in Sydenham.

We saw a vivid lifelike colour picture of his assistant Eddie Anderson, puffing his pipe in front of the camera at the other end of the room. Few people today are aware that my father had a working system of colour electronic television as early as 1945.

In the evening we all went up to the Prince of Wales Theatre to see Jack Buchanan’s new revue, ‘Fine Feathers’.

Jack had known my father since their schooldays together in Scotland 40 years earlier, and he was one of the backers of a new company called John Logie Baird Limited that had been formed to enter the television set market of the postwar era.

After the show we went backstage and we were introduced to Jack. He still had his make-up on, and I was unnerved by the fact that his face was covered with orange greasepaint.

He tried to draw me out by asking me how I had liked living in Cornwall. Ungraciously I said it was “all right”, to which he replied “I just wish I was there now”. That made no sense to me at the time; Cornwall had seemed to me rather gloomy in contrast to the colour and excitement of the theatre.

He tried to draw me out by asking me how I had liked living in Cornwall. Ungraciously I said it was “all right”, to which he replied “I just wish I was there now”. That made no sense to me at the time; Cornwall had seemed to me rather gloomy in contrast to the colour and excitement of the theatre.

But Jack Buchanan’s remark stuck in my mind and it makes more sense now. It came from a talented and hard-working performer who had endured a hectic life for five years and needed a quiet holiday.

In February 1946 my father suffered a severe stroke which confined him to our house in Bexhill. After a while he seemed to be making a good recovery, but he died in his sleep in June 1946.

My mother was left in a difficult position with Diana aged 14 and me aged 11, and with my father’s estate greatly depleted by the expenses of his wartime research. To make matters worse, my mother suffered what was known as a “nervous breakdown”, which is now recognised as clinical depression.

Rescue came in the person of my father’s older sister Annie, who kindly offered to take us in at my father’s birthplace “The Lodge” in West Argyle Street, Helensburgh. During the war she had taken in evacuees, but now the house was inhabited only by Aunt Annie and her faithful housekeeper, Margaret Scott.

On a fresh morning in April 1947, my mother and Diana and I arrived at Helensburgh Upper Station on the sleeper from King’s Cross, and I count that as one of the major events in my life.

“The Lodge” had been bought by my grandfather, the Reverend John Baird, shortly after his marriage in 1878. Annie and my father had both been born there, and the house had passed on to Annie on my grandfather’s death in 1932.

“The Lodge” had been bought by my grandfather, the Reverend John Baird, shortly after his marriage in 1878. Annie and my father had both been born there, and the house had passed on to Annie on my grandfather’s death in 1932.

It stood — and still stands — four-square on the south west corner of the intersection of Argyle Street and Suffolk Street, a solid grey stone villa in a large garden.

The house had been built in about 1870 as a bungalow, but in the 1880s my grandfather had built on an additional floor, the rooms of which had much lower ceilings than the ground floor rooms.

For Diana and me, Scotland was at first a strange place, almost like a foreign country. We both spoke with what was known as the Oxford accent and we were faced with a spectrum of Scots accents.

We had no difficulty in understanding the refined Helensburgh accent, but the local country accent and the Glasgow accent took a little getting used to. Some words in the vocabulary were strange to us: “press” for cupboard and “grosset” for gooseberry.

We had attended Church of England services in the war years but in Helensburgh the Baird family had a strong link with the Church of Scotland.

Soon after arrival at Helensburgh I was enrolled as a day boy at Larchfield, the local preparatory school. It was a happy school, in great contrast to what it had been 50 years earlier when my father had been there.

The headmaster, William (Nobby) Clark was a classicist, a true scholar and a gentleman. With his coaching and encouragement I was able to win a scholarship to Fettes College in 1949. For the first and only time in my life, I sat an exam in classical Greek.

Outside school, life in Helensburgh was extremely quiet 50 years ago. In the days before supermarkets and before most people had cars, shopping — in Scots parlance, “doing the messages” — was a time-consuming and partly social activity. It was done mainly on foot at a leisurely pace, rain or shine; mostly rain in my recollection.

In those days my aunt Annie bought most of her groceries at Mr Johnnie Gilchrist’s small establishment at the corner of John Street and Princes Street. In the school holidays I would often be sent down from “The Lodge” with an order scrawled on the back of an envelope.

Invariably there was a few minutes wait while Mr Gilchrist finished his round of gossip with the previous customer, and then his benevolent attention was turned on me. “Hello Malcolm, how are you getting on at school? And how is Miss Baird today? Terrible weather we’re having.”

After a due exchange of pleasantries, the order was filled and placed in a string bag that I had brought with me for the purpose. Payment was not expected there and then; the items were charged to Miss Baird’s account.

Although no science had been taught at either Sandown or Larchfield, I was becoming interested in two areas of science, radio and chemistry. I started — as my father had done — by setting up a telephone line and communicating over a short distance from room to room in the house.

This soon led to an interest in radio. There was a choice between the simple “crystal set” which needed no electricity supply, and the more powerful type of radio that used valves. Encouragement came from some of the local radio repair shops such as Manderson’s who let me have old radios to take apart and rebuild.

With a few like-minded friends, I built simple one-valve receivers and we quickly discovered that these could be set into oscillation and could thereby be converted from receivers to transmitters.

For several years a friend and I transmitted to each other’s houses over short wave, a distance of about 1 km. This was of course illegal, and after several near misses with the authorities we gave up our experiments.

Chemistry later supplanted radio as my consuming teenage interest. I had started innocuously enough with a bought chemistry set containing “safe” and rather boring chemicals, but this soon moved on to fireworks and even primitive home-made explosives.

With a few confederates I endangered life and limb and the peace of the quiet back streets of Helensburgh. Another achievement was the production of a few millilitres of chloropicrin, a sort of nerve gas.

I must have given many grey hairs to my mother and my aunt, but the only accident was a burn to my hand from a badly behaved mixture containing red phosphorus.

I must have given many grey hairs to my mother and my aunt, but the only accident was a burn to my hand from a badly behaved mixture containing red phosphorus.

Aunt Annie stoically put up with this as she saw a parallel to my father’s teenage exploits 50 years earlier, but my mother was less keen on science and she would have preferred me to take up music.

In those years just after World War Two, there was a general optimism about science and technology. This was reflected in the Festival of Britain in 1951, held in the centennial year of the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace.

Chemistry had a much better public image than it does today and consumers were excited about new products like Nylon, Teflon and fluorescent paint. The upbeat attitude was seen in the Dupont company’s advertising slogan, “better things for better living...through chemistry.”

My enthusiasm for chemistry was strongly reinforced by the Ealing Studios film “The Man in the White Suit” in which a young polymer chemist, played by Alec Guinness, invented an indestructible cloth which never got dirty.

I spent most of my teenage years at Fettes College, an English-style “public” boarding school located in Edinburgh and founded in 1870. It was a gaunt gothic building, standing in large grounds behind a high iron fence.

Within days of arrival I had learned that the cardinal sin was to talk about oneself or boast about one’s achievements. The school sought to mould us as typical English gentlemen, “basically sound chaps” who shunned any form of ego-boosting and played sport for its own sake rather than for the sake of winning.

The lines of Sir Henry Newbolt echoed back to me, “play up, play up and play the game”. As late as 1950, Fettes still had a Victorian ethos based firmly on the four pillars of classical languages, Christianity, cold showers and rugby football.

It was advisable to do well in at least one of these four areas, but my all-round score was low. Science was my main interest but it was considered eccentric and barely tolerable in terms of the classical/humanist culture. The scientists were accused of smelling of chemicals and were generally regarded as being not quite basically sound.

My housemaster “Tom” Goldie-Scott remarked that I should have gone in for classics or humanities which were better for the character than the sciences. He was always the politest of men but his tacit implication was that my character could stand some improvement.

In 1953 it was with a sense of relief that I returned to the quiet life at “The Lodge” and the excellent cooking of Margaret Scott.

I enrolled in the Applied Chemistry programme at Glasgow University and for the first year I commuted every day, catching the 7.42 train in time for the 9 a.m. lecture on mathematics, followed by physics at 10 a.m. and chemistry at 11 a.m. The afternoons were taken up by labs.

It was good to step out of the train into the fresh air of Helensburgh, after a day in Glasgow. The city in those days was still dominated by heavy industries based on coal, steam and steel.

The cobbled streets echoed to the clatters and groans of antiquated tramcars and in the winter months the smog was thick and pervasive. Often it was so dark that the street lights had to remain on throughout the day.

The city centre boasted tea rooms which were oases of Victorian calm and refinement with their starched table cloths and lace curtains, but heavy industry was Glasgow’s life and soul.

To the west, the Clyde shipyards were operating at full capacity and to the east there was a blackened area of foundries, collieries and steel mills. The “dark satanic mills” of William Blake’s great poem were more than just a figure of speech.

After Fettes, Glasgow University came as a profound cultural change. My fellow students were from what was then bluntly known as the working class, a far cry from the basically sound rugby-players of Fettes.

The students were the sons — and a few daughters — of manual workers or low-paid office workers, striving for that pinnacle of middle-class affluence, the four-figure salary.

At the time I had started reading the novels of Helensburgh journalist and author A.J.Cronin, notably “The Green Years”, which resonated strongly with my impressions of life in Glasgow.

In my later Glasgow years I stayed at Kelvin Lodge, a small hall of residence located in the faded grandeur of Park Circus.

In my later Glasgow years I stayed at Kelvin Lodge, a small hall of residence located in the faded grandeur of Park Circus.

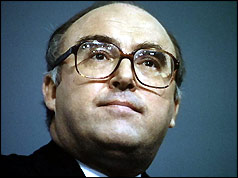

Often I would argue about politics over the dinner table with a keen young Labour supporter called John Smith, who rose to be party leader in 1990 and would have been prime minister but for his tragic early death in 1994.

My life swung back to the English culture in 1957 when I entered Cambridge as a research student, however I still spent most of my vacations in Helensburgh. By 1960 my mother had moved to South Africa and she urged me to emigrate there, but after a visit I decided not to take the chance.

However I took the big step of emigrating to Canada where there seemed to be a good demand for chemical engineers.

After saying my goodbyes I took the little “Granny Kempock” ferry across from Helensburgh to Gourock and boarded the Canadian Pacific liner “Empress of England”. The passengers consisted mainly of people like myself, cheerful young graduates who had joined the so-called brain drain.

As the ship moved slowly away in the bright September sunshine, we could hear the strains of “Will ye no come back again?” from a lone piper on the pier.