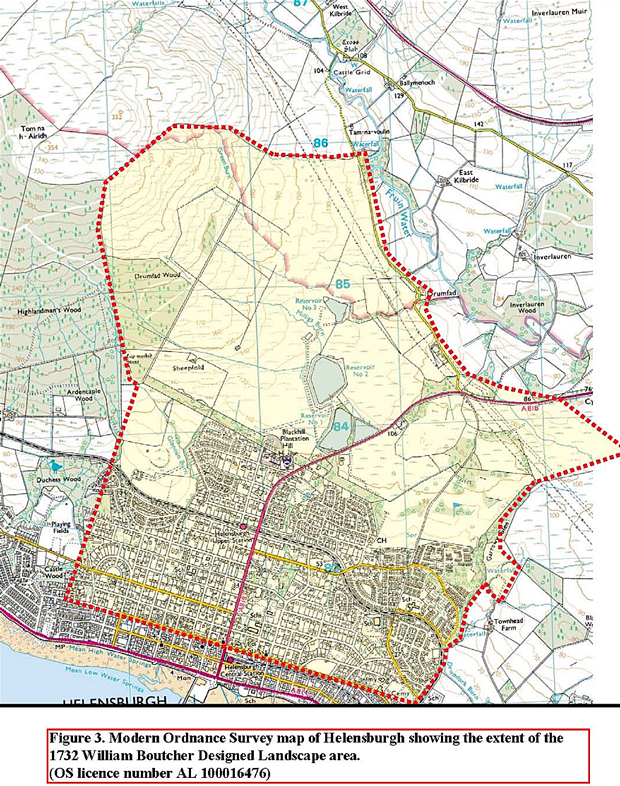

A DESIGNED Landscape by William Boutcher dated to 1732 has recently been recognised on the slope of Tom na h-Airidh to the north of Helensburgh.

The question is — is Boutcher’s designed landscape the genesis of Helensburgh's grid plan layout?

A photocopied map is in Helensburgh Library, but the original belonged to Luss Estate and was probably destroyed in their archives fire,.

The National Library also only has a photocopy. Kathleen Blackie mentioned it in her 1960s MA thesis on Helensburgh but did not think it had been implemented. Mike Davis used to think it was like an advert — ‘Your estate could be like this’.

The existence of the Designed Landscape on the ground was recognised by local historian Alistair McIntyre and subsequent map analysis and local field survey by myself has confirmed its existence.

William Boutcher Senior, nurseryman of Comely Bank, Edinburgh, was active as a landscape designer between 1721 and 1735. He died in 1738.

In the early 1730s he was commissioned to design a gentleman’s estate on the land of Malligs for Sir John Schaw of Greenock, who owned Malligs at that time.

Malligs had been owned by the McAulays of Ardencaple who sold it to Sir John Schaw of Greenock in 1705. He died 1752 and his daughter Marion sold it to the Colquhouns of Luss in 1756.

Boutcher’s other clients included the Duke of Argyll at Inveraray, The Earl of Stair at Castle Kennedy and Lochinch Gardens, Auchincruive, Blair Castle and Duff House.

The online inventory ‘Parks and Gardens UK’ describes his style as similar to Charles Bridgeman and that he was capable of formality, variety and irregularity. But really we know very little about him

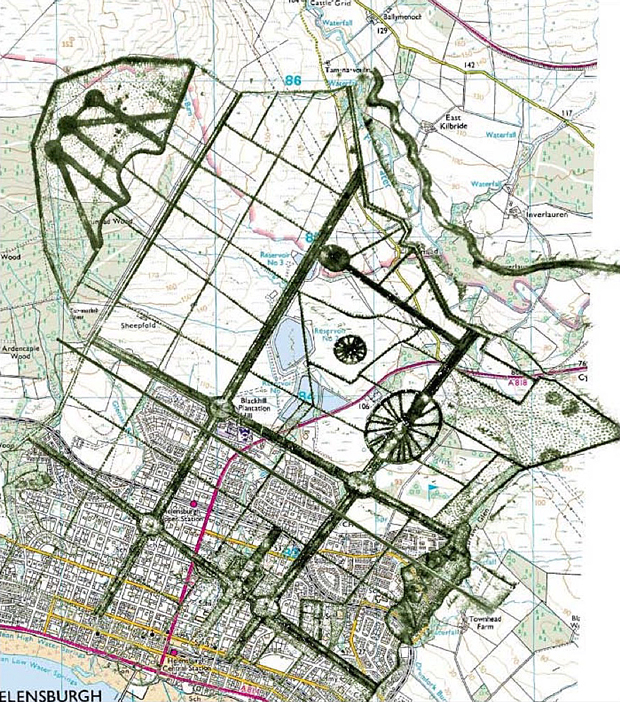

Boutcher worked in the formal French style of the late 17th and early 18th century, and his 1732 plan for Maligs is a classic example of early 18th century formal parkland with an emphasis on geometry and formality with linear tree lined avenues and focal points — for example the Golf Course belvedere and Hermitage Park location.

Boutcher designed in the late 17th century French idiom which was going out of fashion by the 1730s, as the Picturesque movement typified by Lancelot Capability Brown became fashionable.

When Sir James Colquhoun embarked on the design of Helensburgh from around 1780 a different landscaping style was in fashion. However, laying out planned villages can also be traced back to around 1735.

Boutcher’s map is entitled ‘The Generall Plan of the Land of Malligs belonging to the Honourable Sir John Schaw of Greenock Knight and Baron. Drawn at Comely Gardens, April 1732, by William Boutcher’.

Examination of Boutcher’s map indicates many local reference points that can be located on later maps. There are also many useful annotations on Boutcher’s map indicating place names and land ownership.

For example the location of Malligs Mill and the mill pond is clearly marked as well as two Malligs representing Middle Malligs and Glenan or Eastertown shown on Ross’s 1776 map.

Campbell of Ardenconnel is shown owning the lands on the west boundary. Drumfad, mentioned in charters since the 13th century, as is Malligs ,and as is the location of the Horse Fair.

Boutcher’s design shows wide tree lined avenues — roads — which intersect at belvedere roundels, and roughly rectangular parcels of land divided up by tree lined banks.

Boutcher’s design shows wide tree lined avenues — roads — which intersect at belvedere roundels, and roughly rectangular parcels of land divided up by tree lined banks.

The belvederes or roundels, a classic element of the French formal style, were designed as viewing places and located in commanding positions to look over the landscape and provide features of interest. The spokes represent avenues leading out from the central high spot.

Two fairly well preserved remnants of belvederes can be identified at Hill House car park and Helensburgh Golf Course. Detailed field survey may locate the other belvederes and the one to the south of the golf course survives in part as an island of woodland.

The belvedere that survives at the top of Helensburgh Golf Course appears to represent the central high spot and the outer oval bank. Both features can be located on the ground but no convincing trace of ‘spokes’ has so far been located. The two north west-south east banks to the east of the roundel are also present.

Of course the Blackhill Coup, in use from the early 19th century, has caused considerable disturbance to any archaeological remains in this area.

The surviving section of Boutcher’s design that is now the popular walking route to the west from the Hill House car park, which is one of the belvederes, appears to have been planted, as does the surviving section to the east which runs to the golf course.

The banks are clearly apparent, and a number of ancient oak and beech trees may represent Boutcher’s planting plan.

The main avenues that survive at the Hill House walk and on the Three Lochs Way are represented by two banks forming an avenue up to 20 metres wide.

The main avenues that survive at the Hill House walk and on the Three Lochs Way are represented by two banks forming an avenue up to 20 metres wide.

On Old Luss Road at the belvedere the banks are ten metres apart and it seems there is variation in width of the avenues. The double parallel banks are indicative of Boutcher’s Designed Landscape.

Highlandman’s Road is shown on Boutcher’s Plan as a straight north-south double bank and these banks are present, but elements of the earlier drove road route may also survive.

However, the construction of the Three Loch’s Way — done without any archaeological input — has cut across these banks in two places.

The straight nature of Highlandman’s Road and also the Old Luss Road are of note in that they align with Boutcher’s plan. It is unusual to have two old drove routes running not only dead straight rather than meandering, but also parallel to each other.

The change in the alignment of the street grid pattern in the south east part of the town at Queen’s Court may also represent a relict element of Boutcher’s design. The change in alignment at Stuck is also apparent on Charles Ross’s 1776 map which reflects Boutcher’s 1732 map almost exactly.

The other striking element of Boutcher’s plan that is represented in the modern townscape of Helensburgh, though not in the form designed by Boutcher, is the location of Hermitage Park.

It appears that not all of Boutcher’s landscape was implemented. The area where a recent wind turbine proposal was located is shown as wooded and with three or four belvedere roundels and a series of banks.

This area has not been inspected in detail on the ground by the author and would be best examined in the winter when the vegetation is down. However, no sign of any earthworks are visible on Google Earth satellite imagery whereas the other elements of the designed landscape are all visible on Google Earth.

Comparison of Boutcher’s plan and the modern Ordnance Survey map indicates that the Designed Landscape was implemented to some extent in the early 18th century, and a great deal of what Boutcher mapped and designed survives as a relict landscape today.

General William Roy’s Military Survey of 1747-55 does not show any distinctive elements of Boutcher’s designed landscape.

Roy generally does show designed landscapes, but its absence might reflect that it was not planted up and only the banks were laid out so it would not have been highly visible. Also it would only have been 15-20 years old at the time.

Roy also does not show the designed landscape at Inveraray in any detail and it must be noted that the Duke of Argyll and Sir John Schaw both fought against the Jacobite cause so Roy would have had less cause to focus on their lands than on mapping the land of Jacobite sympathisers.

The next known map of Malligs is the 1776 Charles Ross map on which several elements of the Boutcher Designed Landscape can be identified.

Sir James Colquhoun purchased the Land of Malligs from Sir John Schaw of Greenock’s daughter in 1752. The Schaws had owned the Land of Malligs from 1705 to 1752 and it was previously part of the McAulays of Ardencaple Estate.

Sir James Colquhoun purchased the Land of Malligs from Sir John Schaw of Greenock’s daughter in 1752. The Schaws had owned the Land of Malligs from 1705 to 1752 and it was previously part of the McAulays of Ardencaple Estate.

Sir James commissioned Charles Ross to survey Luss Estate in the 1770s

Charles Ross’s 1776 ‘A Plan of the Barronie of Malig with Drumfad. Belonging to Sir James Colquhoun Baronet. Surveyed and Planned by Charles Ross’ shows the various farm feus stretching roughly south to north from the shore.

Ross was employed to survey and plan all of Luss Estate before Sir James embarked on a major plan of improvement.

Again geo-referencing would be required to determine which of the land boundaries shown on Ross’s map correlate with Boutcher’s plan, but examination of the maps indicates that Stuck Park in the south east of the town and some of the linear boundaries are exactly the same features.

The modern street alignment in the vicinity of Stuck also suggests a vestige of the Boutcher Designed Landscape.

Unfortunately Ross’s map does not include the northern part of Malligs in detail and this area is left blank and identified as Mains Park and Brocklie Park.

Some of the boundaries and banks shown by Boutcher and Ross may already have been in existence as agricultural feus.

Certainly earlier Estate boundaries, which may date back to the Medieval period, are present, and the outer boundary, the boundary of Malligs, may have been defined as far back as the early 13th century by Maldouin of Lennox who issued many land charters around 1225 including Ardencaple, Drumfad, Camis Eskan, Colgrain and Ardenconnel.

It seems to be at about this time that the local area was parcelled up into defined estates.

Boutcher’s map identifies the land to the west as Ardencaple owned by Colin Campbell, the land to the north as Drumfad owned by Colquhoun, and the land to the east as Colgrain.

Indeed the reflection of earlier feus seems likely as the settlements at Malligs, Eastertown and Glenan — shown as two Maligs on Boutcher’s plan — are all earlier than the 1730s and the feu layout shown by Ross indicates at least a late medieval date for these agricultural holdings.

Milligs, Stuck, Colgrain, Kirkmichael and Drumfad are all shown on Pont’s map of 1590 and all are shown on Ross’s map, but only Milligs (x 2) and Drumfad are named on Boutcher’s map.

Both Ross and Boutcher show Malig Mill and the nearby chapel, reflected in the name Chapel Acre, and both show buildings at Kirkmichael. Most striking is the exact representation of Stuck Park on both maps.

The house and garden at Stuck on Boutcher’s map is shown on Ross’s map and although the layout is not exactly the same, two buildings shown on both maps may be the same structures.

The Old Luss Road is annotated as the Duke’s Road as it was upgraded by the Duke of Argyll in the later 18th century. Culoist (Ross) and Colshcliech Hill (Boutcher) is currently an unknown location that requires further research, but may be the area of disturbed earthworks on the south side of the road just before Drumfad Farm.

At the approximate location of the belvedere at the top of Helensburgh Golf Course it is of interest that Charles Ross has annotated his map ‘There is to be seen from this place the Firth of Clyde, Greenock, Newport, Gourock, Elrie(?), Rosneath, Ardencaple; together with the famed Loch Lomond and its Isles, with Drummond, Buchanan, Stirlingshire, Perthshire, Argyllshire, Dumbarton and Renfrewshires.’

It is possible that Boutcher largely imposed his design on top of whatever already existed in terms of land boundaries.

The apparent straightening and re-alignment of the old drove roads of Highlandman’s Road and the Old Luss Road suggests that Boutcher took cognisance of what was already present in the landscape, and incorporated and modified it to fit and reflect his overall design.

The subsequent design of Helensburgh as a planned new town typical of Enlightenment era planning may have incorporated elements of Boutcher’s Banks in its grid pattern design.

The main design showing the grid patterns and feus is by Peter Fleming in 1803.

Fleming’s grid appears at first glance to be on a slightly different alignment to Boutcher’s Banks, but further detailed surveying and geo-referencing is required to determine what if any elements of the Boutcher Designed Landscape may survive in the town’s grid pattern lay-out.

Certainly in the south east of the town where the alignment of the streets changes slightly, for example Henry Bell Street, the boundaries shown by Boutcher and Ross at Stuck are reflected in the present street layout.

Peter Fleming’s 1803 feu proposal really appears to have been drawn in an office with very little reference to the topography of Malligs.

Highlandman’s Road is a Church Road or Coffin Road and is identified on John Thomson’s 1823 map as such. It was in use as a Church Road for the inhabitants of Glen Fruin to reach Row Parish Church and it can be dated to the mid-17th century at the latest.

However, Highlandman’s Road may be a late medieval route and is certainly a drove road which linked Glen Fruin to the Gareloch at Rhu.

Cattle and horses were swum across the Gareloch from Rosneath to Rhu Point and also transported by ferry.

This is the most southerly Argyll drove route and the main southern route was generally Mark to Portincaple and then via Whistlefield to Strone in Glen Fruin.

It was normal practice for drovers to swim the beasts across narrow crossings, and there was a major cattle fair — Dumbarton Tryst — held latterly at Carman hill above Renton. It attracted around 8,000 cattle each year in the early 19th century.

There was also a horse fair at Drumfad, Glen Fruin, which was certainly in operation around 1700 and perhaps earlier, and the site is shown on Boutcher’s plan.

Highlandman’s Road is described as a cart road by Battrum in 1864, and it was refurbished by the Dowager Duchess of Argyll in the mid-19th century.

It was apparently straightened and formalised by Boutcher, and this is represented on the ground by two parallel banks which, had Boutcher’s plans been fully executed, would have been planted with trees on the banks.

The Spence 1857 proposal for Helensburgh is more interesting as it reflects some things that are present and the crescents – fashionable at the time – may reflect old roundels, for example the Charlotte Street-Victoria Road junction, and Barclay Drive.

The existence of Boutcher’s Designed Landscape appears to have faded from local knowledge by the mid-19th century.

Battrum’s ‘Guide to Helensburgh’ of 1864, describes the belvedere on the Old Luss Road on the golf course as an ‘ancient camp’.

Later described by the Ordnance Survey as a 35m diameter earthwork and perhaps as an ornamental woodland feature, it was not recognised as an element of Boutcher’s Designed Landscape.

1732 is carved on the well known cup and ring marked boulder above Ardencaple wood, the very date of Boutcher's survey and surely no coincidence.

Given that the Boutcher Map is nearly 300 years-old, it is not surprising that it is not an exact fit on modern Ordnance Survey mapping. However, the proximity of modern boundaries to Boutcher’s Design can leave no doubt that a significant Designed Landscape exists.

It might even be fair to say that Boutcher’s Banks are the genesis of Helensburgh.