THE MOST generous benefactor in Helensburgh’s history believed that divine intervention had saved his life, and giving was his way of expressing his gratitude.

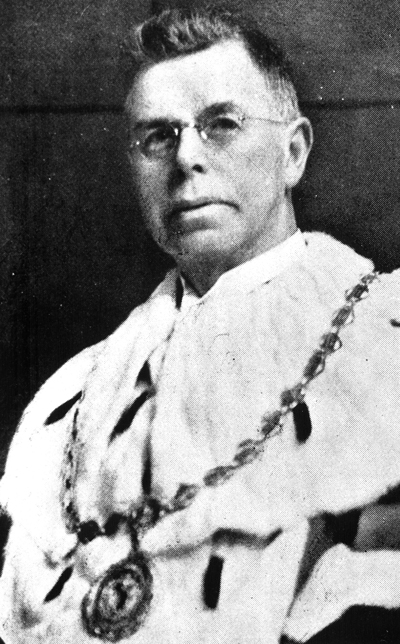

Not only did Provost Andrew Buchanan pay for the King George V Silver Jubilee beakers and sweets given to town schoolchildren in 1935, but he is best remembered for donating the outdoor swimming pool.

He also paid for regalia and chairs for the Provost and Bailies, a paddling pool at the foot of James Street, refurbishment of the Victoria Halls to mark the Silver Jubilee, and repairs to Old Luss Road. Privately his generosity was just as great.

His son Ian confirmed that his generosity stemmed to a great extent from his father’s very narrow escape from death by food poisoning in what became known as the Loch Maree Tragedy of 1922.

Ian said a few years ago: “He was terribly upset by this tragedy, and he thought it was divine intervention that he was spared. So from that day on he gave away his money to countless causes in Helensburgh and elsewhere.”

Local historian Alistair McIntyre has researched the tragedy, and this is what he discovered . . .

The whole episode centred on the Loch Maree Hotel, which in August 1922 was full with visitors and holidaymakers. The loch was world-famous for the quality of its sea-trout fishing.

On the morning of Monday August 14, thirteen of the hotel guests went fishing, among them Andrew Buchanan, who was affectionately known as ‘Sweetie’ Buchanan because of the family involvement in confectionery manufacture.

They were supported by seventeen ghillies and boatmen, and two of the fishermen had their wives with them.

The hotel was in the habit of supplying guests engaged in outdoor pursuits with packed lunches, enough food for both guests and ghillies.

On this occasion, some of the sandwiches contained the contents of a jar of potted wild duck paste.

Andrew was in a boat with John Stewart, a well-known Glasgow businessman and angler on the loch for 40 years, and John Mackenzie, a local man who was acting as their ghillie.

In due course, they stopped to have lunch. However, when Andrew took a bite of one of the sandwiches, one mouthful was enough to somehow kill his appetite — although he said afterwards that there was nothing obvious about the taste or smell to put him off.

He threw away the rest of the sandwich, which saved his life. The rest he gave to his ghillie. The others had their lunch as usual. The afternoon was uneventful and all the guests returned to the hotel.

John Stewart was taken unwell early the next morning, and before long, several other people who had eaten packed lunches the previous day also began to feel ill.

The local G.P., Dr Knox, was soon on the scene. Some of the symptoms were alarming, including double vision, dizziness and muscle weakness. One patient complained that he could only open his eyes by pulling up his eyelids.

Even so, the seriousness of the illness had yet to be revealed. John Dixon, of Dublin, even decided to try to throw off his indisposition by having a four mile row on the loch, joking to his ghillie that if a fish rose, he would be able to see two instead of one.

By now, however, Dr Knox was becoming so concerned that he decided to consult some medically qualified people who were holidaying in the area, including Professor T.K.Munro of Glasgow University, and Dr Dickson, a Harley Street physician.

By the time Professor Munro arrived at the hotel on Tuesday evening, John Stewart had passed away. At 70 years of age, he was the oldest of those afflicted.

While Dr Knox and Professor Munro were there, the condition of Mrs Dixon, who had accompanied her husband, rapidly deteriorated, and before midnight, she too had died.

Some form of food poisoning was already suspected, in particular the packed lunches.

Among the hotel guests, illness was restricted to a number of those who had consumed packed lunches, while significantly, one of the ghillies, none of whom had dined at the hotel, was among those complaining of symptoms.

Further questioning of those affected seemed to point the finger at certain sandwiches containing potted meat paste.

However, although the consensus was that food poisoning was almost certainly responsible, the exact nature of the illness remained unclear — and with events having taken such a dramatic turn for the worse, the matter was referred to the office of the Procurator Fiscal.

By Wednesday, Andrew’s ghillie, John Mackenzie, was among those feeling unwell, while two more patients at opposite ends of the age spectrum died that same day, the elderly Mr E.G.Williams from London, and John Talbot from Kent, a gifted 22-year-old student studying at Oxford.

Dr William McLean, Chief Medical Officer of Health for Ross and Cromarty, had swiftly come to realise that the symptoms were practically identical to those he had read about in several German magazines, where a Van Ermergen had described in 1895 the effects of a pathogen responsible for causing botulism.

By Friday he had sent his report to that effect to the Procurator Fiscal. Subsequent analysis of samples taken proved that he was absolutely correct in making this diagnosis.

On Thursday Mrs Anderson, who had accompanied her husband, Major Anderson, on the Loch on Monday, and their ghillie, local man Kenneth McLellan, both died.

Major Anderson, on leave from service in the Indian Army, was unaffected by illness, not having consumed any of the sandwiches.

The newspapers were reporting that there was hope that two other patients would make a full recovery. Such hopes were soon dashed, with John Vickers Dixon passing away on Monday August 21, and John McKenzie losing his battle for life late the same day.

All of those who had fallen ill, eight people, lost their lives within a week.

At the Inquiry held at Dingwall Sheriff Court on September 5, the jury found that no-one was to blame for the terrible tragedy.

Several popular accounts published over the years implied that the hotel had been cavalier in its approach to food safety, this being aided and abetted by hot weather and the absence of refrigeration equipment.

But scrutiny of the Inquiry findings reveals that the hotel, which had never before had any problems of this nature, had been scrupulously careful in handling the food used for the sandwiches, certainly in terms of best practice of those times.

The firm of Laxenby’s, which had supplied the meat paste, was found not to have been negligent in any way in its production and distribution processes. The firm was highly regarded, with an excellent safety record.

What the jury did recommend was that vessels containing preserved meat, fish, fruit or vegetables should bear distinct marks by which details of manufacture could be traced.

Samples were taken from the fateful jar — only one was found to be contaminated — and sent to Bristol University for analysis.

Even though the traces recovered were tiny, there was more than enough to demonstrate that the Botulinum pathogen was present, and the toxic products generated by the strain were lethal.

It was estimated that a quantity of meat paste equivalent to a pinhead’s worth contained enough toxin to kill 2,000 mice.

The recovery of what has come to be known as the Buried Sandwich, proved a vital back-up. When ghillie Kenneth McLellan had been given his share of sandwiches, he had eaten them, bar one, which he placed in his pocket.

After being taken unwell, he had mentioned this, and a family member retrieved the sandwich. It was evidently suspected that the contents were dangerous, because it had then been buried, for fear that the hens might eat it.

This incident was later mentioned to the authorities, who dug up the sandwich, and despatched it to Bristol for analysis. It was found to be as deadly as the sample from the jar.

So how did Andrew Buchanan survive? At the Inquiry, he could not recall having spat out the one mouthful he took, yet if he had consumed even a tiny amount of meat paste, there is little doubt that he would have been among the dead.

The Sheriff asked him: “Are you quite sure one or some of these potted sandwiches was given to the ghillie, John Mackenzie?” He replied: “Yes.”

The Foreman of the jury asked: “Did you swallow the bite?”

He replied: “I have no recollection of spitting it out, so I must have swallowed it.”

According to his son, the police examined the area where his boat had stopped for lunch. They found two dead seagulls close to where the sandwich was thrown.

The Loch Maree case has been described as being the first in the British Isles where botulism was proved to be the cause of death, and it is thought to represent the worst case ever to have taken place in that area to this day.

Ian Buchanan stated that the Loch Maree case did not have any subsequent effect on the use of potted meat products at the family home, Dean House, in East Abercromby Street.

But in the wake of such a terrible tragedy, it is perhaps inevitable that there were certain consequences. The effects on Alexander Robertson, the proprietor of Loch Maree Hotel, were devastating.

But in the wake of such a terrible tragedy, it is perhaps inevitable that there were certain consequences. The effects on Alexander Robertson, the proprietor of Loch Maree Hotel, were devastating.

Although he was completely exonerated of any shortcomings at the Dingwall Inquiry, and had a fine record as host at Loch Maree for twelve years prior to the tragedy, he subsequently died of a broken heart.

The scale and scope of Andrew Buchanan’s contributions to the public good, to charitable causes, and to individuals was quite outstanding.

The gift of an outdoor swimming pool (right) to Helensburgh in 1929 meant an outlay of at least £6,000. Today’s equivalent would be about £300,000.

It was closed in the late 1970s and was replaced by an indoor pool, but in 2006 a heavy metal plaque which marked the opening of the outdoor one was re-erected at the present pool by the Heritage Trust.

A very different example came in the form of financing improvements to Old Luss Road in 1932. Here the aim was not only to provide an amenity for walkers, but also to provide work for unemployed people at a time of economic depression.

After the Loch Maree tragedy he also gave support to the two unmarried sisters of his ghillie, John Mackenzie.