Journalist Colin Donald tells the story of his great uncle, Cardross man George Chrystal, who died in one of the first World War One gas attacks at Ypres in 1915.

WHAT do we know of great uncle George Chrystal?

That he was an only son, elder brother of four sisters living in Edwardian comfort at Bloomhill House at Cardross.

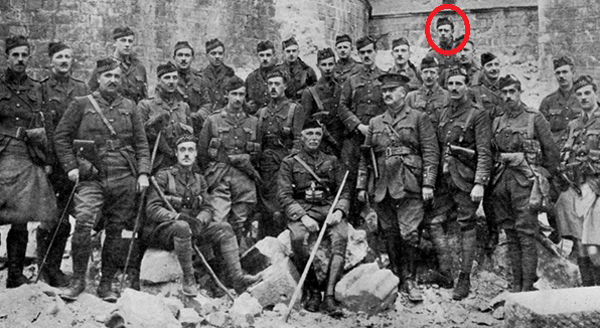

That he was a serving territorial soldier sent to France as Lieutenant the 1/9th “Dumbartonshire Battalion”, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders following Germany’s surprise attack on Belgium in August 1914.

That he was an Oxford graduate, eligible bachelor, a not excessively martial but dutiful part-time officer.

We know that he was killed, perhaps suffocated in one of the Western Front’s first ever gas attacks, somewhere in the woods near Bellewaarde Lake at the end of the Second Battle of Ypres, on May 24 1915.

We also have his letters, preserved in a tan leather folder by my great-grandmother who, like so many others, never recovered from his loss.

She retired to darkened rooms, imposing his ghost on her too-young grandchildren in a manner considered “morbid” by some contemporaries.

We don’t know — and never will know — where Geo (pronounced Joe) is buried, or even if he was. We do know his name is on panel 42 on the Menin Gate at Ypres.

Geo’s niece, my aunt Mary, born within a decade of the armistice, has lived with his heroic absence since childhood.

I have been editing his letters, and working on a plan to develop a disabled ex-servicemen’s housing project at Bloomhill in his memory.

With Remembrance Sunday approaching, we both felt that a visit to Ypres — Ieper as its Flemish-speaking residents prefer — were an overdue gesture to Geo that he was still remembered, even loved, in an abstract way.

On the flight to Brussels we perused the collection of 40 neatly written letters and postcards to “Moth and Fa”, dating from 17 August 1914 when Geo left from Stirling for training at Bedford, transferring to France in February 1915, thence to the bulge in the Flanders front line known as the Ypres Salient and his rendezvous with death.

By today’s standards, the birthright he was leaving behind him in Cardross was one of considerable luxury. Bloomhill — “Bloomers” as he called it — is an imposing though not especially attractive 1830s mansion, surrounded by elaborate and well-tended gardens, fields, gate lodges, and outbuildings.

This roughly 20-acre estate, a short daily walk from Cardross station, belonged to George's father, John G. or “Jack” Chrystal who was an insurance broker with the Glasgow firm Mackenzie Roberts & Co.

It is not known when the Chrystals acquired Bloomhill, but as George was born in La Belle Place in Glasgow’s West End in 1885, it was presumably soon after that, to accommodate a growing family.

Four daughters, the youngest my grandmother Mabel, followed the birth of George, the son and heir.

As George died unmarried, the Bloomhill mini-estate was broken up on his father’s death in 1948. The fields alone were retained by the family, while the house served various civic functions, including as a “boys home”.

For many years it has been a home for the elderly, changing ownership in 2012 to become the Clyde View nursing home.

The letters from the Front that the village postman would have conveyed up Bloomhill’s then neat gravel drive every few days reveal Geo to be a conscientious leader to “the men”, many of them industrial workers from the Dumbarton and Clydebank.

The concentration of shipbuilding and other “reserved occupations” in the area was given as a reason that the 1/9th “Dumbartonshire” Battalion was relatively slow to reach full numerical strength, a sensitive issue given the competitive patriotic fervour of the early months of the war.

As far as it is possible to tell, George seemed to have a genuine empathy with the men, and his letters are full of requests for cigarettes and sweets on their behalf.

He frequently urged his mother to leave what would have been a gentrified comfort zone to go to the tenements of Clydebank to visit young wounded returnees, and regimental widows.

Apart from in the heat of battle, officers did of course have it relatively easy compared to these men.

To contemporary ears there is a touch of Blackadder Goes Forth in Geo’s repeated thanks for the pheasants, port, champagne, haggis, chocolate, “toffee biscuits”, shortbread, hard boiled eggs and other luxuries with which he was showered by anxious relations and friends.

“I got the shirt, towels and woolly slippers, which are splendid for wearing in the evening,” he writes in one letter.

There is a surreal contrast between these home comforts and his “pretty strenuous” circumstances, and in the mental image of him in a dank and rat-infested dugout penning polite enquiries about the health of various aunts.

But this theme cannot be pursued too far. Officers — including Geo’s battalion commander, Colonel James Clark, an Edinburgh barrister — were shelled and gassed as efficiently as other ranks in World War One, 431 in the Argylls alone.

Geo was neither jingo-ist, nor a disillusioned critic of the futility of it all — he didn’t live long enough.

His letters home remained heroically jaunty: “It is the German custom to give the British troops who relieve the French a pretty warm reception — we certainly came in for it this time”.

“Nothing much to do thro’ the day, and trench digging by night . . . nothing to grouse about”.

These letters mean a great deal more to anyone who has spent time in Ieper, and been able to see the various relics of the war which put them in context, plus the scraps of World War One information accrued over the decades.

The process of fitting mental pictures to some charged words — Hill 60, Langemark, St Julien, Kitchener’s Wood — makes the events described closer.

Like our own, the Flanders government is planning a series of events to mark the centenary of the start of the “war to end all wars” in October 2014, honouring the generation whose grip on collective conscience seems only to strengthen.

Flanders is investing €50m in upgrading infrastructure in anticipation of a 30-40% increase in the current annual 350,000 “peace tourists” in the Salient.

Geo’s battle will be marked by a separate chemical warfare conference in 2015.

Although by any standards George Chrystal could have been said to have had a lucky life until the outbreak of war, it was his and his part-time soldier comrades’ supreme misfortune to have been present at what must have been one of the worst days in the history of the British Army.

Poisoned gas was always a terrifying weapon, but the unexpectedness of this horror on its first use defies imagination. Those who lost loved ones were nevertheless condemned to imagine it, perhaps for the rest of their lives.

Even Geo’s sanitised account of that battle leading up to that point could not disguise the darkening awareness of a new kind of war that first revealed itself in massive casualties of the bombardment and gassing.

The Imperial War Museum Book of World War One describes 2nd Ypres, in which 105,000 died in the only major German offensive of 1915, as “particularly brutal and savage, fought in anger and without compassion or quarter“.

Geo calls it “a horrible business altogether, which one has to do one’s best to forget.”

“Dear Moth,” he writes on May 12, two days after 300 men and 12 brother officers were killed near Hooge, “I am so sorry I haven’t been able to write sooner and hope you have not been very much worried about it.

“The scrapping here has been too strenuous for the post to go with any regularity. I’m afraid you will gather from the casualty lists what a tough time we have had, before you get this letter.

“It really has been awful, but I think and hope that the worst of the business, as far as we’re concerned, is now over and that there is a chance of us being relieved quite soon.”

Visits to the First World War battlefields are now the stuff of routine school excursions — maybe compulsory ones, according to a recent suggestion by Prime Minister David Cameron.

Neither my aunt nor I had ever been on a battlefield tour or experienced the sophisticated and sensitive sector that caters to this market.

Centred on the Grote Markt, Ieper, or “Wipers” as Commonwealth troops called it, which was flattened by repeated bombardment while Geo was at the front, images of its smashed carcass had the same impact on his generation as those of Hiroshima did a generation later.

The intensity of fighting in 1914-18 — there were five separate Battles of Ypres — mean that it is fated to be the hub of the battlefield tourist trail which follows the line of trenches stretching 450 miles to France’s Swiss Border.

According to the letters, George and his men were billeted in the relative comfort of a “sort of nunnery”, until it was blown to bits.

According to the letters, George and his men were billeted in the relative comfort of a “sort of nunnery”, until it was blown to bits.

In letters from the firing line he expressed a rueful affection for Wipers: “I don’t fancy we shall be billeted there again. It is a pity — life there was comparatively civilised, and there was quite a decent ‘coiffeur’ if one cared to wait tso hours for a haircut.

“I haven’t had my clothes or boots off, nor had a shave for, for over a week now and we are a dirty looking crew”.

Nowadays the knowledge that German resentment over reparations helped cause World War Two casts a shadow on the placid, brick-built historicality of the town, but its recovery has a more uplifting message, best contemplated in the autumnal early morning light along the 17th century ramparts, now a kind of circular park.

I won’t easily forget coming across the clean, pale ranked grave stones of the Ramparts Cemetery by the Lille Gate on an early-morning jog. Impeccably kept like all Commonwealth War cemeteries, its lawn sloping gently down to the moat.

A similar emotional gut-punch was the first sight of the Menin Gate, built over the road along which men marched to the Front.

Caught in the evening sunlight, this unique stretched neo-classical arch, grand but not pompous, was built in 1921 by Sir Reginald Blomfield, the Elgar of Edwardian architecture.

It contains the names of the 55,000 Commonwealth soldiers who have no known grave.

We visited again for the Last Post — a bugle ceremony held at 8pm every night since 1928 which attracts huge crowds, especially around Armistice Day.

It was easier than expected to find Geo’s name, on panel 42, under the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, “Lieutenant GG Chrystal”. We slipped a Scottish-type poppy into a groove in the masonry.

That day we had spent the afternoon with Lest We Forget Tours, one of several Ieper-based companies specialising in battlefield tours.

It is hard to conceive of a better one than this, led by a former Royal Tank Regiment NCO, Chris Lock.

A Flemish-speaker who has lived there for years, Chris has an intimate knowledge of the Ypres battles and deftly improvised a trip tailored to what I was able to tell him of Uncle Geo’s service and death.

Chris had a dramatic, empathetic way of bringing the action to life, and of transporting us imaginatively as well as literally to the field of battle.

He took us to the Essex Farm Dressing Station, on the Yser Canal, one focus of the 2nd Battle of Ypres, April-May 1915, a good guess as to where Geo met his end, on May 24, 1915.

It was the final phase of a battle that started in panic following the German release of chlorine gas, the first time that chemical weapons were used on the Western Front.

“We had a little taste of the ‘poisonous gas’ business,” Geo writes home on May 18, “and one or two men were laid out by it. We all had to wear wet respirators [wet with urine, he doesn’t add], which are some protection against it — even the little we had made one’s eyes very sore.”

What exactly happened to the men whose names now adorn Dunbartonshire war memorials is not known, as the regimental war diary has a gap from May and July, and the chaos of the ensuing months seems to have prevented the proper identification of the dead, let alone the writing of a comprehensive account, which must be pieced together from survivors stories in contemporary press accounts.

This lack of record of the circumstances in which George’s 1/9th Battalion was — in the words of military historian Trevor Royle — “all but wiped out” became a source of bitterness in the following months, as the lack of a description of their sacrifice was blamed on a clerical “blunder” resulting in confusion with another battalion.

As the Kirkintilloch Herald wrote on August 11: “It was a considerable disappointment to Dunbartonshire when [BEF Commander Field Marshall] Sir John French’s despatch covering the Second Battle of Ypres was published and was found to contain practically no reference to the share in the fighting of the 9th Argylls.

“Something, it was thought, was wrong when a battalion which had lost two commanding officers, nearly all its company officers and 75% of its men was hardly mentioned.”

The best thing to be said about the decimation of the 1/9 Battalion Argylls at the end of this battle was that they were spared its sequel, 3rd Ypres, better known as Passchendaele, two years later (June-Nov 1917).

Geo’s battle, although one of the bloodiest of World War One, was at least short.

The muddy carnage of Passchendaele ranks with the Somme (July-Nov 1916) as a symbol of World War One futility.

A short drive from Ypres lies the flint-walled Tyne Cot ceremony, with its 35,000 graves, the largest Commonwealth cemetery in the world, next to it a sleek modernist visitor centre commanding the crest of the gentle rise for which so many lives were lost.

Passchendaele’s story is told in a museum in the village of Zonnebeke a few miles from Ypres, whose basement is a recreation of a dugout, the wooden-walled underground complexes, infested with rats, in which men survived for months.

Such places contrast with the flat, quiet, timeless Flanders countryside between them with its dead-straight, tree-lined roads running between the boxy red-brick farms and hamlets.

In a letter written three weeks before his death, Geo takes note of this surreal contrast between serenity and violence.

In his mind’s eye, the placidity and traditional order of Cardross, which he may have taken for granted all of his young life, must have seemed as potent to him as to anyone in the village’s long history.

“There’s really no news that I’m allowed to give I so I will stop,” he wrote. “It must be lovely at home just now, we all get beastly homesick at times and the spring seems to make it worse.

“This wood is a queer mixture of green leaves, violets, nightingales and shells — but we might be much worse off than where we are.”

His last letter dated May 23, the day before his death, is brief and bland, thanking his mother for the “shaving tackle of a very superior kind! And also a mixed lot of eatables and cigarettes which arrived today + clean shirts, socks etc. Excuse a PC. I’ll write again as soon as poss.”

The story of what then happened in that wood is taken up in a surviving soldier’s record, displayed in the Argylls’ regimental museum at Stirling Castle.

It reads: “We were up against overwhelming odds for days, the Germans were trying to break our lines. The 9th kept up a brisk rate of fire on the advancing Germans who lost a terrible amount of men but we ourselves lost heavily.

“The wood was raked by shelling which seemed to scorch every yard of it . . . trees were smashed like matches. When the shelling ceased hardly a tree remained standing, all was a jumble of broken timber beneath which lay dead men, broken rifles, equipment and torn sandbags.”

Reading the letters of one of those dead men, close to where they were written, cuts through the intervening 100 years.

While it is hard to judge anyone from what they tell their parents, seemingly unassuming Geo might be surprised — and gratified — at the enduring potency of his and his comrades’ deaths. Or rather of all the lives they did not get to live.

Colin Donald is Business Editor of the Sunday Herald and Group Deputy Business Editor of the Herald Times Group, and a version of this article appeared in the Herald Magazine of November 11 2012. He writes: “If any reader has any information relating to the history of 1/9th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, or of Bloomhill House, I would be grateful if they could contact me at

Colin Donald is Business Editor of the Sunday Herald and Group Deputy Business Editor of the Herald Times Group, and a version of this article appeared in the Herald Magazine of November 11 2012. He writes: “If any reader has any information relating to the history of 1/9th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, or of Bloomhill House, I would be grateful if they could contact me at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .”