OFFICIALLY it is the A83 Trunk Road. For centuries however travellers have known it as the Rest and Be Thankful.

At the top they have welcomed the chance to draw their breath and enjoy the view as they crossed the summit at 860 feet on the road that leads from Loch Long to Loch Awe via Glen Croe and past the picturesque Butterbridge into Glen Kinglas.

There can be few roads in Scotland so well documented by travellers over the centuries or so affectionately named as the Rest.

In the beginning, of course, there was not a road at all. There was just a track, a path, made by generations of travellers, and beaten out by herds of black cattle being taken by drovers from Argyll to the trysts and cattle markets of the Lowlands.

The making of a road, in any sense that we would now recognise it, had to wait until the 18th century. Some work was done in the 1730s on roads in Argyll by local government agencies — the Commissioners of Supply.

However the real impetus for road building came after the 1715 and 1719 Jacobite Risings.

General George Wade was sent to Scotland to examine the military situation in the Highlands. His report made a number of recommendations, including the construction of forts at various points and the development of a network of roads to link these strong points.

In 1743 it was decided to construct 44 miles of military road from Dumbarton to Inveraray, via Loch Lomondside, Tarbet, Arrochar, Glen Croe and thus down to Loch Fyne.

In 1743 it was decided to construct 44 miles of military road from Dumbarton to Inveraray, via Loch Lomondside, Tarbet, Arrochar, Glen Croe and thus down to Loch Fyne.

Major Caulfeild, Wade’s Inspector of Roads and successor as mastermind of the Highland roads network, was ordered to survey the route and work started that summer — although progress was interrupted by the outbreak of the 1745 Jacobite Rising.

The Old Road

However this was a rather strange military road. The Wade/Caulfeild roads were built to link military bases in the Highlands, and to help keep down the disaffected areas by allowing the rapid movement of troops into potential trouble spots.

A route up Loch Lomondside leading to Crianlarich, Tyndrum and Fort William was an obvious military necessity, although the Tarbet to Crianlarich section had to wait until 1752/4 to be built.

However Argyll, and Inveraray its capital, was a strongly Hanoverian, pro-Government area, firmly under the control of the Duke of Argyll, one of the leading figures in the government of Scotland. What military purpose was to be served by this road?

It was hardly likely that a detachment from the garrison at Dumbarton would have to be marched to Loch Fyneside to put down an insurrection in the peaceful glens of Argyll.

Two possible reasons exist for the high priority given to this road. The first reason may have been to allow the pro-Government forces that could be raised in Argyll, and indeed a regiment of the Argyll Militia fought in the Culloden campaign, to move swiftly from Loch Fyne to wherever they might be needed.

The other reason was perhaps less straightforward, but perhaps more plausible — to provide a conveniently smooth road to and from the Lowlands for the Duke of Argyll.

The connection between the road and the Duke was emphasised by Caulfeild, when the road was nearly completed, money was running out and there was a danger that a bridge at Inveraray could not be completed.

Caulfeild wrote that “this will hurt a great man for the bridge is at his door” — as indeed it was, being barely a mile from Inveraray Castle, the Duke’s seat.

After Culloden work recommenced and by 1748 troops from the 24th Regiment, later the South Wales Borderers, had made the road over the summit of Glen Croe and erected a stone seat with the legend “Rest and Be Thankful.” Completion of the route to Inveraray was achieved by 1749.

Roads need maintained and detachments of soldiers carried out upkeep on the road and in 1768 the 93rd Regiment, the Sutherland Highlanders, repaired the summit stretch.

Their work is recorded in a later commemorative slab (left) preserved in what is now the car park at the summit.

Their work is recorded in a later commemorative slab (left) preserved in what is now the car park at the summit.

The next significant step came with the creation of the Commissioners of Highland Roads and Bridges in 1803 with a remit to build and maintain communications.

The Rest and Be Thankful road was handed over to the Commissioners by the military in 1814 — a date inscribed on the stone which records the 93rd Regiment’s work.

However even before the road became a civil responsibility it had been a popular route with many of travellers who came in increasing numbers to visit and write about Scotland in the second half of the 18th century.

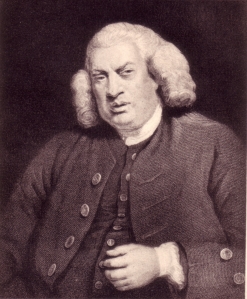

The naturalist and traveller, Thomas Pennant, crossing the Rest southbound in 1769, had nothing more to say of it than: “Ascend a very high pass with a little lough on the top of it”, but Samuel Johnson, travelling four years later from Inveraray back to the Lowlands at the conclusion of his “Highland jaunt” noted that he and James Boswell:

“… proceeded Southward over Glencroe, a bleak and dreary region, now made easily passable by a military road, which rises from either end of the glen by an acclivity not dangerously steep, but sufficiently laborious. In the middle, at the top of the hill, is a seat with the inscription “Rest, and be thankful.”

Stones were placed to mark the distance, which the inhabitants have taken away, resolved, they said, to have no new miles.

Johnson’s description of the landscape as bleak and dreary may in part be explained by the season — it was late October — but it also reflects the conventional opinion of his age on wild scenery. Johnson and his contemporaries were more inspired by urban life, or by well-ordered parkland, than they were by untamed nature.

Johnson’s description of the landscape as bleak and dreary may in part be explained by the season — it was late October — but it also reflects the conventional opinion of his age on wild scenery. Johnson and his contemporaries were more inspired by urban life, or by well-ordered parkland, than they were by untamed nature.

In 1784 a French scientist, Barthélemy Faujas de St Fond, travelled to Scotland, attracted by the remarkable geological formations of Fingal’s Cave on Staffa.

His route took him up Loch Lomondside, which he delighted in, however he soon left these “flowery and verdant” shores and tackled the ascent to the Rest.

He wrote: “I soon found a contrast to the delightful scenes we left. They were succeeded by deserts and dismal heaths. We entered a narrow pass between two chains of high mountains, which appear to have, at a very remote period, formed only one ridge, but which some terrible revolution has torn asunder throughout its length.

“This defile is so narrow, and the mountains are so high and steep, that the rays of the sun can scarcely reach the place and be seen for the space of an hour in the twenty-four.

“For more than ten miles, which is the length of this pass, there is neither house nor cottage, nor living creature except a few fishes in a small lake, about half way.”

Faujas explains that he ignores the sheep grazing the hills as they were so far away they could be taken for stones. He goes on to comment, perhaps rather surprisingly in view of other traveller’s remarks, on the lack of repair of the road.

Faujas explains that he ignores the sheep grazing the hills as they were so far away they could be taken for stones. He goes on to comment, perhaps rather surprisingly in view of other traveller’s remarks, on the lack of repair of the road.

He wrote: “We travelled thus for nearly six hours in this dismal traverse, through which the roads are neither metalled nor kept in repair.”

Whether the military had neglected the road since Dr Johnson’s visit or whether the Frenchman was expecting a higher standard of road maintenance than perhaps was reasonable in the Scottish hills is now debatable.

What is clear is that the impressive landscape of Glen Croe had provided a remarkable, and not entirely welcome, contrast to the gentler scenes of Loch Lomond.

In 1796 Sarah Murray, the widow of Captain William Murray, RN, made an extensive tour in Scotland and wrote a guide book and manual for travellers, A Companion and Useful Guide to the Beauties of Scotland.

She advised travellers to furnish themselves with a “strong roomy carriage” and such useful equipment as “half a dozen towels, a blanket, thin quilt and two pillows” and also provided notes on places of interest and recommended routes.

Her comments on her approach to the Rest, from Glen Kinglas in the north, have much in common with our earlier travellers:

“The carriage road…turns to the right, up one of the most formidable as well as most gloomy passes in the Highlands, amongst such black, bare, craggy, tremendous mountains, as must shake the nerves of every timorous person, particularly if it be a rainy day.

“And when is there a day in the year free from rain in Glen Croe? and on the hill called Rest-and-be-Thankful? No day; no not one!”

However Mrs Murray, who does not seem to have been in the least timorous, found much to move and delight her in the wild landscape: “Glen Croe … has charms for me, and I was sorry to lose sight of it.”

By the beginning of the 19th century travellers in Argyll had come to appreciate the grandeur of the scenery and the route up Glen Croe to the Rest was no longer seen as a “dismal traverse” but as something to be relished.

In 1803 the poet William Wordsworth, his sister Dorothy and their friend the poet Samuel Coleridge came on a tour of Scotland and in late August planned to travel from Arrochar to Inveraray. However Coleridge fell ill and left the Wordsworth’s at Loch Long.

Dorothy’s diary records the fact that they were not the only travellers on the road — she noted a coach with four horses, another carriage and two or three men on horseback, evidence that the road was at that time well enough maintained for heavy wheeled traffic.

The Wordsworths themselves travelled in a one-horse Irish jaunting car, dismounting and walking on the steeper sections to relieve the strain on their horse.

Entering Glen Croe Dorothy observed a cottage in the lower part of the Glen and its solitude immediately appealed to her — a clear sign of changing tastes in landscape:

“The dwelling in the middle of the vale was a very pleasing object. I said within myself, How quietly might a family live in this pensive solitude, cultivating and loving their own fields.”

The travellers had experienced heavy rain at Arrochar but the weather brightened as they ascended the Rest and Mary reflected on the picturesque aftermath of the storm: “that afternoon and evening the sky was in an extraordinary degree vivid and beautiful.”

At length they came to the summit of the road with: “…a seat with the well-known inscription Rest and be thankful.

”On the same stone it was recorded that the road had been made by Colonel Wade’s regiment. The seat is placed so as to command a full view of the valley, and the long, long, road, which, with the fact recorded, and the exhortation, makes it an affecting resting-place.”

Sadly the seat and the inscription are no longer to be found there, nor is it at all certain that there ever was a reference on it to Colonel Wade. By the time the summit stretch was built Wade was a Field Marshal, and he in fact died in March 1748.

The work was done by troops under the command of Colonel Lord Ancram, but the identification of every military road in Scotland with Wade, whether or not he had ever seen it, had clearly taken hold by the time of the Wordsworths’ visit and persists to this day.

William also reflected on the area in a later sonnet “Rest and be thankful” [At the head of Glencroe] from which these lines are taken:

Doubling and doubling with laborious walk,

Who, that has gained at length the wished-for Height,

This brief this simple wayside Call can slight,

And rests not thankful?

An amusing sidelight on the problems of travel in an age before Ordnance Survey maps, guidebooks and Tourist Information Centres made vacation planning easy is given by the experience of another poetical visitor to the Rest.

John Keats came north in 1818 on a walking tour with his friend, the writer Charles Brown. Keats’ terse diary entries tell the tale of their encounter with the Rest:

“We were up at 4 this morning and have walked to breakfast 15 Miles through two tremendous Glens — at the end of the first there is a place called rest and be thankful which we took for an Inn — it was nothing but a stone and so we were cheated into 5 more Miles to Breakfast.” As his friend Brown later wrote: “horror and starvation!”

In the early period of motoring the Rest and Be Thankful was a popular test for the hill-climbing abilities of cars.

In the early period of motoring the Rest and Be Thankful was a popular test for the hill-climbing abilities of cars.

In 1906, the novelist Neil Munro, in search of copy for his weekly column in the Glasgow Evening News, went on a four-day reliability trial around Scotland organised by the Scottish Automobile Club.

Munro was a passenger in a 15hp Darracq car and after successfully negotiating most of the route he found himself at his birthplace, Inveraray, with just the run back to Glasgow to be completed.

A series of timed hill climb stages on some of the steepest and highest roads in Scotland was behind them but the pioneering motorists and their passengers faced one last, unofficial, challenge.

As Munro wrote: “And yet the most astonishing hill of all — though not recognised as such officially — was before us after we had lunched at the Argyll Arms Hotel, Inveraray; fifteen miles from Inveraray we had to climb the Rest and be Thankful, where all the automobiles in the West of Scotland seemed to have gathered to watch us.

“It was when the Rest was won, and we looked back on the sombre depths between the mountains of Loch Fyne, and before us to the ribbon of road that zig-zagged for a little before us, then plunged into the abyss of long Glencroe, that most of us must have felt the supreme thrill of this four days of trial.”

The increasing volume of traffic made improvements essential and various minor improvements were made in 1920s and 30s with some of the worst gradients being smoothed out on the Glen Kinglas approach.

In the inter-war years the Rest remained a notoriously difficult route for cars and lorries. The present author’s father recalls that in the early 1930’s he was a passenger in an Albion lorry that was forced to reverse up the final hairpin bend.

The condition of the Rest and Be Thankful road even featured in an editorial in the London Times in 1926. The leader writer pointed out that Highland roads were breaking up due to tourist traffic and that their maintenance was an impossible burden for the ratepayers of the Highland counties.

A new and ambitious scheme, planned to commence construction in 1931 was delayed due to the national economic crisis.

This proposed to reconstruct the road from the county boundary at the head of Loch Long to the summit at the Bealach an Easain Duibh — a distance of seven miles — and was finally started in 1937 at a cost of £100,000 (about £4 million at current prices).

The funding came from Central Government as part of a crofting counties roads scheme — an initiative to deal with economic development issues in the Highlands, a curious echo of the original Government funded military road, designed to deal with another sort of Highland problem.

The old road continued to be used after the Second World War as a testing hill climb route for racing and sports cars. Most of the old road still can be seen today and something of the challenge it once presented judged.

The Rest and Be Thankful may be a much tamer road in the 21st century, smooth, well engineered and well maintained, and its condition would doubtless surprise Faujas de St Fond or John Keats.

But the spectacular scenery through which the road runs remains much as it was in 1838 when the Scottish judge, Lord Cockburn, returning from administering justice in Inveraray, wrote:

“The day was perfect for that glorious stage from Cairndow to Tarbet. Few things are more magnificent than the rise from Cairndow to Rest-and-be-Thankful.

“The top of it, where the rocky mountain rises above the little solitary Loch Restil, and all the adjoining peaks are brought into view, is singularly fine.

“As I stood at the height of the road and gazed down on its strange course both ways, I could not help rejoicing that there was at least one place where railways, and canals, and steamers, and all these devices for sinking hills and, raising valleys, and introducing man and levels, and destroying solitude and nature, would for ever be set at defiance.”

- This article by the late Brian D.Osborne is reprinted on this website by kind permission of the author’s father, Malcolm Osborne.

■ MEANWHILE a group of veteran car enthusiasts, known simply as Friends of the Rest and consisting of 72 members including several from Helensburgh, united in 2009 with the sole purpose of restoring the Rest as a motoring heritage site.

They launched a DVD of 1950 motoring events to raise money for the essential repairs needed for the Rest, keeping potholes in check and repair subsidence, landslips and flood damage.

In recent years the hillside road has been plagued with regular landslips, despite efforts to mitigate the results, and the Old Military Road has often brought into use with a convoy system. Now the Scottish Government and Arfyll and Bute Council are leading efforts to find a viable alternative.