A STEWARDESS from Helensburgh is one of two women named on the Helensburgh War Memorial in Hermitage Park.

Janet Todd of the Merchant Navy lost her life on March 25 1941 in one of the more controversial sinkings of World War Two.

She was born on January 5 1891 at what was then called 1 Upper Maitland Street and became 1 Grant Street.

This was the home of her parents, coal miner’s son George Todd and his wife Flora MacNiven, a fishmonger’s daughter, and they later moved to 57 West Clyde Street.

Both died before the war, Flora from cancer on March 9 1928 aged 64 and George from heart disease on November 5 1938 aged 72.

A carter, then foreman carter, George retired as foreman of the Helensburgh Town Council Cleansing Department.

They also had a son George and another daughter Maisie, and it was several weeks after Janet’s death that Maisie was told, and she then placed a death notice in the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times.

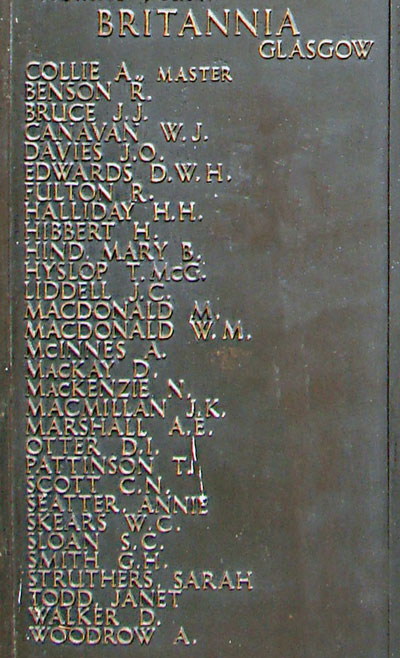

The weekly paper also reported: “Intimation has been received by Miss Maisie Todd, 57 West Clyde Street, that her sister, Miss Janet F.Todd, who was for many years a stewardess with the Anchor Line, was among those lost and presumed drowned when the liner Britannia was lost in March as the result of enemy action.”

The weekly paper also reported: “Intimation has been received by Miss Maisie Todd, 57 West Clyde Street, that her sister, Miss Janet F.Todd, who was for many years a stewardess with the Anchor Line, was among those lost and presumed drowned when the liner Britannia was lost in March as the result of enemy action.”

It was enemy inaction after the sinking which caused some controversy at the time.

Janet, who was 51, was the chief stewardess on board the liner SS Britannia which was bound for Bombay via the Cape.

She was attacked by the German raider Thor 750 miles west of Freetown and sunk with the loss of 249 of the 492 crew, service personnel, and passengers aboard.

Janet and three of her staff, stewardesses Mary Bernardine Hind (30), Annie Seatter (48) and Sarah Struthers (48), are thought to have drowned.

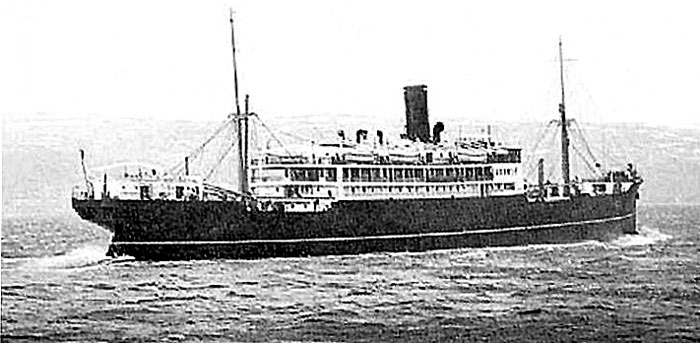

Britannia was built for the Anchor Line by Alexander Stephen & Sons at Linthouse, Govan, and launched in 1925. Her maiden voyage from Glasgow to Bombay started on March 3 1926, and she was used on this route thereafter.

On March 11 1941 Britannia, operating as a troop ship under the command of Captain A.Collie, set out from Liverpool to Freetown, Durban and Bombay.

The voyage began with the Britannia as a member of a convoy with an anti-submarine escort. By March 25 the rest of the convoy had disappeared and Britannia was on her own.

Early that morning she was attacked by the German Hilfskreuzer — auxiliary cruiser — Thor, also a converted merchant ship, under the command of Kapitän Otto Kähler.

The Thor was armed with six 5.9 inch guns and easily overpowered the liner. When her single rear 4 inch gun was destroyed Captain Collie gave the order to abandon ship.

Britannia’s radio operator had managed to get off an RRR (Raider, Raider, Raider) signal with her location, which was acknowledged by Sierra Leone radio.

The Thor picked up radio traffic which indicated that a Royal Navy warship was on its way at speed. Kapitän Kähler later claimed that, in the light of this information, he did not stay to pick up survivors.

After giving warning and allowing time to abandon ship, he shelled the Britannia on her waterline and she sank quickly.

He heard later that no warship had arrived and that some of the survivors had spent many days on rafts and in lifeboats before being picked up by other ships which were in the area.

The survivors took to the ship’s lifeboats and some threw baulks of timber overboard and used them as makeshift rafts. But many died at sea as they waited to be rescued.

Lifeboat Number Five carried about fifty survivors who were picked up by the Spanish ship Bachi.

The Spanish ship Cabo de Hornos was in the area five days after the sinking and picked up 2nd Lieutenant Cox, Sub Lieutenant Davidson and Lieutenant Rowlandson from the ‘1st Raft’.

On board the Cabo was a French Baroness who, with Rowlandson, persuaded the captain to keep searching.

They later picked up Spencer Mynott and Alfred Warren from the ‘2nd Raft’, and survivors from another raft, and two lifeboats, a total of 77, who were taken to the island of Tenerife.

The MV Raranga rescued 67 and took them to Montevideo. Four more survivors on another raft were picked up by another Spanish ship.

After 23 days at sea, 38 survivors reached the coast of Brazil on Lifeboat Number Seven, having navigated across most of the Atlantic, and this was claimed to be the longest ever journey by a lifeboat at the time.

One survivor, 24-year old Fitter Alfred Warren, of the Fleet Air Arm, arrived home in Birmingham to join his young wife in time to celebrate the first anniversary of his wedding.

For five days and four nights he had floated on a flimsy raft while one by one six of his exhausted comrades were washed away. When only one other man was left, clinging on feebly, a Spanish rescue ship at last hove into sight.

Hope flickered anew, but fate had not yet finished with Alfred Warren. As he dipped his leg into the sea to paddle the raft one of the sharks keeping sinister vigil suddenly came closer and sank its teeth into his calf.

Looking down in horror at the monstrous snout, with frenzied strength he kicked his foot free from the shark’s mouth before his leg was snapped off, but not before the muscle in his calf had been severed.

He told his local paper later that, with what he described as typical Nazi inhumanity, the enemy raider wasted no time in trying to save survivors after shelling Britannia.

Instead the Thor steamed off at speed, leaving hundreds of men and women, scattered over the face of the sea, some crowding into the overloaded lifeboats, others struggling in the water or clinging to crazy rafts or bits of driftwood.

“The raider chased us for more than two hours,” he told a reporter. “Half our boats were holed by gunfire.”

Of his time on the raft he said: “We were tormented by hunger and thirst and blazing heat. One man, a tea planter, went mad with the exposure.

“When we were picked up there was only one man, a naval telegraphist, left with me. All the others were lost one by one.

“We lost track of time. Often we were in a state of coma. On the fifth day we both had the hallucination that we were on part of the deck of a ship.

“To our fevered imagination it seemed that people in evening dress kept coming on deck, bringing drinks which they offered to us.

“To our fevered imagination it seemed that people in evening dress kept coming on deck, bringing drinks which they offered to us.

“I spent ten weeks in hospital. Gangrene set in, but the surgeon at Tenerife saved my leg. At present I can just manage to walk. Now that I’m home on leave for three weeks I’m going to take life very quietly.”

Another survivor, Lieutenant Commander Frank West MBE, wrote a book, Lifeboat Number Seven, dealing in detail with the loss of the ship and his subsequent voyage from the sinking point to the coast of Brazil.

Janet’s name is on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Tower Hill Memorial in London (left), designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens who also designed the Ferry Inn at Rosneath.

The other woman named on the Burgh Cenotaph is Acting Sister Emily Helena Cole.

South African-born Helena, whose widowed mother lived at Sunnyside Cottage, 36 West King Street, from 1905-14, served with the Queen Alexandra Imperial Nursing Service in World War One.

She died from meningitis at the 14th General Hospital in Wimereux, Boulogne, on Sunday February 21 1915 at the age of 32.