A WELL-KNOWN Rosneath Peninsula man played an important role in the discovery of a sunk submarine in 1951 because of his involvement with the development of underwater television.

Former Kilcreggan Primary School and Hermitage School pupil John Revie — known to all as Jack — took part in finding the wreck of HMS Affray, a submarine which mysteriously sank with all hands off the Channel Islands.

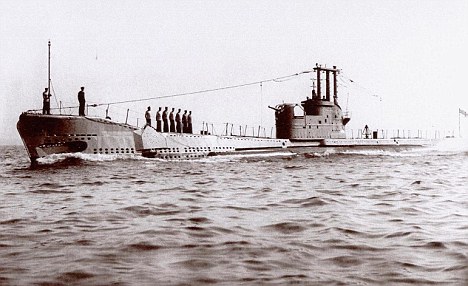

On April 16 1951, Affray, a five-year-old Amphion-Class submarine, left Gosport harbour on a training exercise with a crew of 75. Four hours later, after the Captain signalled that he was diving, all contact was lost.

As rumours began circulating about possible sabotage, the unseaworthiness of the vessel and other less likely explanations for its mysterious disappearance, a frantic search for Affray began.

Two months later, a possible location in “Wreck Valley” off Alderney was confirmed by the first practical application of underwater television.

This apparatus, lowered from the rescue ship HMS Reclaim, had been developed by a team at the Admiralty Research Laboratory — led by Rosse Stamp and including Jack — in a project codenamed Lacquer.

It was Stamp who, while watching the on-board television monitor in the captain’s cabin, first saw the periscope standards and radar aerial, and then the name of the submarine on the conning tower.

The Affray (left) had been found — at a depth of 280 feet.

The Affray (left) had been found — at a depth of 280 feet.

Walter Rosse Stamp was born in Sidcup on August 11 1925, the younger of two sons of Edith Parsons and Charles Alfred Stamp, a chemist who had served in the Royal Navy during World War One and a director of a family firm of South London ‘high-class grocers’ and cafés.

As well as his Aunt Bertha, a leading artist of the time, Stamp had two remarkable uncles.

The elder was the economist and civil servant, Sir Josiah Stamp, later the first Baron Stamp, who became chairman of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway; the younger was Sir Laurence Dudley Stamp, a famous geographer.

Rosse Stamp studied physics at King’s College, London, graduating in 1945. He then joined the Department of Scientific Research at the Admiralty, conducting research into the applications of photography to naval science.

In 1950 he was transferred to work on television, “on the doubtful grounds,” he later recalled, “of having built a home televisor.”

When Affray disappeared the following year, the celebrated wartime frogman, Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb, who was already working as a civilian, for the Admiralty Research Laboratory, immediately offered his services to help find the sub. Crabb would himself disappear five years later, in even more mysterious circumstances, in Portsmouth Harbour under the Soviet cruiser which had brought Bulganin and Krushchev to Britain.

Stamp was considering the possible use of closed-circuit underwater television in the search but, as a junior scientific officer, was not in a position to implement the idea.

He said later that to have contacted a high-ranking officer “would have been an improbability bordering on the fantastic — or the insubordinate.

“All such communication was the province of much higher authorities, with the exception of Buster, who was a law unto himself and invaluable in having a foot in both camps.”

According to Crabb’s biographer, Marshall Pugh, Stamp approached him for help, but “Crabb was in a strange position. All his diving life he had cursed scientists, electronic engineers, civil servants and his views on them were well known to the Navy.

“Stamp lived in another world from Crabb. He had a lathe in his dining-room and electronic fly killers of his own invention round the house. Crabb would not call on him — he said he was scared of being electrocuted.”

Crabb and Stamp subsequently became friends, with the latter convinced that the former slept in his rubber wetsuit.

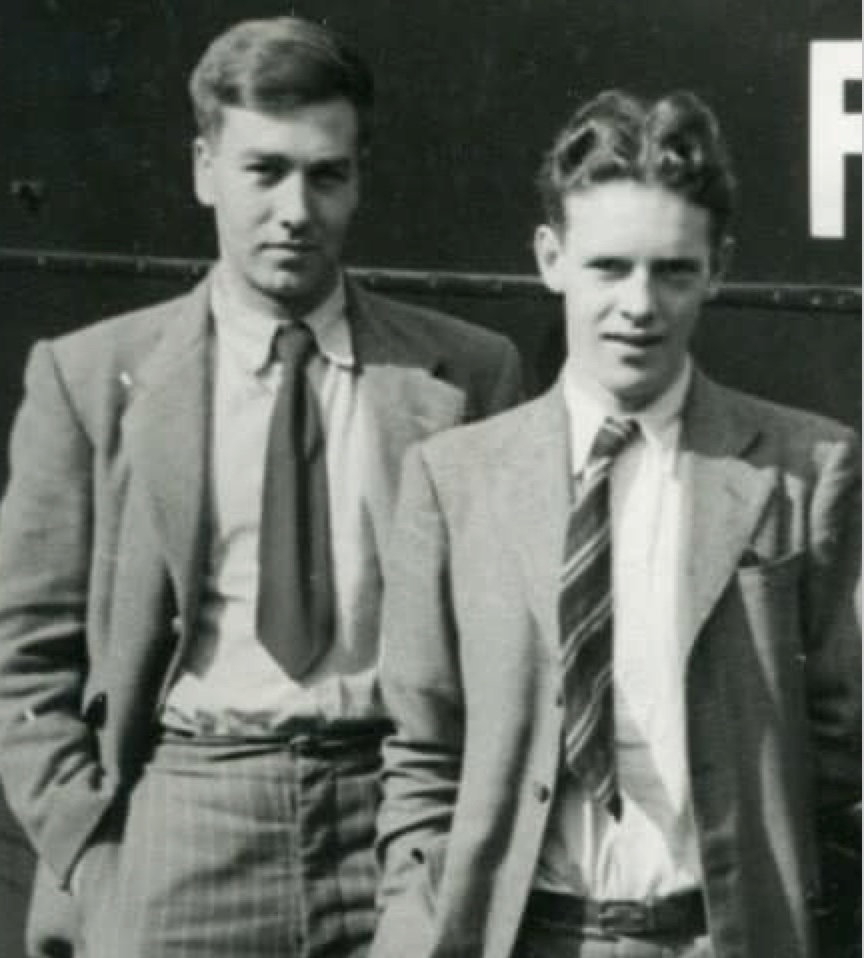

In the event, a team was assembled by Dr Nyman Levin consisting of Stamp, Crabb, R.B. ‘Jock’ Phillips, an older Scots engineer, and his assistant and compatriot Jack Revie — “all”, as Stamp put it, “inclined towards unorthodoxy.”

Shielded by the Official Secrets Act and working in isolation to bypass all red tape, Stamp and the team built a waterproof casing like a large dustbin for the conventional television camera already ordered from the Marconi firm.

Next they designed a framework, with a powerful searchlight attached, to allow it to be steered underwater.

When the television had found the submarine, Stamp received no public recognition, even though it was almost certainly the first use of a television camera underwater and the first time that a wreck had ever been identified by underwater television.

When the television had found the submarine, Stamp received no public recognition, even though it was almost certainly the first use of a television camera underwater and the first time that a wreck had ever been identified by underwater television.

He later wrote: “I did not originate the idea of using TV to identify Affray — I might have done, had I known of the problem — but it was not until Buster arrived back and reported his experiences that the fun started.”

The mystery of the Affray endures, as a Board of Inquiry produced no answers. The Royal Navy declined to raise the sunken vessel, giving rise to suspicions of a cover-up, and successive governments refused to reopen the inquiry.

The wreck was declared an official war grave in 2001 and may not be interfered with.

Stamp went on to write several papers and gave talks and broadcasts on underwater television, which he advocated as “capable of working deeper than a diver and for longer periods even than an observation chamber.”

It also avoided any risk to life.

He was slightly dismayed by the way the discovery of the Affray was portrayed in the press, later insisting that the only completely accurate account of UWTV was published in the Children’s Newspaper.

Later he worked on anti-submarine detection systems and then on sonar systems for Britain’s nuclear submarines.

He died on June 30 this year, and it was the publication of an obituary for him which alerted friends of Jack and told them of his part in the Affray search.

Jack Revie was born in 1930 at the family home, Brookvale Cottage, Knockderry Road, Cove. His father was an engineer with the Clyde Valley Electricity Company — coincidentally where TV pioneer John Logie Baird worked as a young man.

He grew up at Cove, went to Kilcreggan Primary School, and then to Hermitage School where he was considered to be a bright pupil.

After the Affray exploration he specialised in working with torpedoes. He returned to live on the peninsula, and worked at Lochgoilhead, the Arrochar torpedo testing range, Greenock and Coulport.

He married his English wife Joyce Mina Lambert in Middlesex in 1954, and they had two daughters and a son.

When they came back to Cove, they bought a bungalow named Heathcroft, also on Knockderry Road. Finally, Jack built a new house which he named Glencroft, in what had been part of the extensive rear garden at Brookvale, a Victorian villa at the corner of Shore Road and Knockderry Road.

Joyce, who was very involved with the Girl Guides, died in 2005 at the age of 76.

Jack joined Cove Sailing Club in 1947 and he was a keen yachtsman all his life. Even when he lived for a time in Perranporth, Cornwall, he enjoyed the sport of sand yachting.

Jack was also a very keen and highly respected gardener. He was a prominent member and eventually chairman of Helensburgh and Gareloch Horticultural Society, and took many prizes at the annual show.

He died in April 2017 in England, where his daughters had been caring for him.