ALTHOUGH the Second World War came along shortly after I did and it extended through my younger years, I have only fond memories of that period in Helensburgh.

The fact is that I have always found it difficult to imagine a better childhood.

That said I, in these early years, did not appreciate the concerns of the many mothers and children who had a father who was away from home and in possible danger in one of our services.

My father’s trade caused him to be assigned to an ordnance factory. He also served in the Home Guard, equipped with a rifle but no ammunition, and assisted in my grandfather’s pub, so I seldom saw him, but at least he was at home.

I was born in a small house on King Street, just east of Sinclair Street. But shortly after my second birthday in 1938 I moved with my family to Ardencaple Quadrant.

I remember that expedition, I had to walk with my mother; it was only about a mile but to a two-year-old it was an endless trek.

At that time The Quadrant was somewhat different than it is today in that it was as far as houses were concerned the west end of Helensburgh There were a few beyond on Cairndhu Avenue, generally referred to as ‘The Bungalows’, but not many others.

At that time there was nothing south of the Quadrant except West King Street, a stretch of untended fields, the side by side estates of Cairndhu and Ferniegair, Clyde Street and finally the River Clyde Estuary.

The Ardencaple Castle gardens and grounds lay to the west and the Castle Woods rather densely covered the north and east sides. It was a wonderfully quiet place where no person, to my knowledge, owned a car.

King Street ended at Cairndhu Avenue, ended rather abruptly with a brick wall with an inset door-less man-door. Vehicular traffic could only access the bungalows and the castle driveway from Clyde Street.

Our house was on the north side of the Quadrant so its back garden ended at the Castle Woods. A wire and stake cleft fence defined the woods edge, but by the time I was four that was only a minor inconvenience.

As one would expect the housing development had its share of young children and the woods became our playground. It was an almost magical place populated by many birds, rabbits and other small animals.

Each spring there were patches of wild snowdrops, then crocuses followed by immense carpets of daffodils and bluebells. The only dark side was the almost daily patrol of a man and his black Labrador.

My parents suggested that he was likely a gamekeeper and while that, to four or five year-olds, explained little or nothing, we were convinced that he probably ate small children for dinner — so we gave man and dog a wide berth.

The more formal grounds adjacent to the castle could easily be accessed from the woods but we seldom got close to them — largely because that area got the greatest attention from said man and dog, but also because other than the odd gardener hoeing weeds or occasionally cutting the lawn nothing ever seemed to happen.

When we did venture to the edge of the woods we could look left across the poorly tended lawn to the castle entrance and right to a cluster of undefined buildings. In time we were to discover that they formed a courtyard with aging stables and storage sheds at ground level and small flats above.

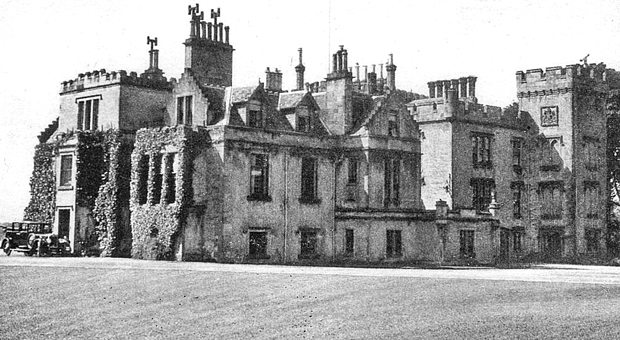

Although Ardencaple Castle entered my life around 1940 it had been very much a part of other lives for more than seven-hundred years. Some years ago I wrote a novel that tangentially involved the castle, causing me to develop a modest understanding of its history that I believe to be fairly accurate.

While this takes us away from my story it may be of interest . . .

The original small castle, or ‘keep’ as it would have been called, was built early in the 13th century and was the property of the Earl of Lennox. In 1249, Lennox sold the building and the surrounding lands to a Maurice Macaulay, and Maurice promptly declared his extended family to be the Macaulays of Ardencaple.

Apparently no one took exception to the declaration and the Macaulays began a long tenure. Ardencaple Castle, complete with additions built in both the 15th and 16th centuries, remained their family home for 518 years.

As time passed the Macaulays either failed to reproduce in sufficient numbers, were killed defending their lands, or they simply moved from the area.

Whatever the reason, the last head of the small clan at Ardencaple, named Aulay Macaulay, put the castle up for sale in 1767. The buyer was General John Campbell, the Fourth Duke of Argyll.

History does not explain why Campbell bought yet another castle when he apparently had difficulty maintaining, but not defending, the several he already owned. Nevertheless General John and his descendants made several more additions to the castle, and, 95 years later in 1862, sold it to Sir James Colquhoun of Luss.

Colquhoun, a minor baron with a large estate bordering on Loch Lomond, already owned much of the adjacent land, and since 1776 his family had been developing the area into what in 1802 became the small town of Helensburgh; named after his wife Lady Helen Sutherland.

In 1923, the Macaulays, through an American named Mrs. H.Macaulay-Stromberg, again became the owners of the castle. She in turn sold it to a Mr J.D.Henry who apparently held the title through the outbreak of war in 1939 and until around 1942 when the His Majesty’s Royal Navy appropriated it.

Back to my story . . .

So, in 1942 when the Royal Navy arrived I, at age six, had no idea why they either wanted or needed a castle. Since our country was at war another ship would have seemed more appropriate.

According to my father, who volunteered explanations, right or wrong, for everything and anything, the Navy had set up their West of Scotland headquarters in our castle because the Clyde Estuary was a major centre of naval activity, with enormous shipyards close to Glasgow and the Home Fleet anchored in the Gareloch. The area was also relatively free from Luftwaffe attacks, or so they/he thought.

It took some time for me and my friends to realise that the Navy had arrived, although we thought that something may have happened when for several days there was no sign of the so-called gamekeeper and his black Labrador dog.

One day in we walked through an unpatrolled Castle Woods and made our way to the edge of the castle lawn — there we were amazed by what we saw.

The few castle gardeners, usually the only sign of activity, were gone and replaced by an uncountable number of men and at least a dozen arriving and departing lorries; all, men and lorries, in navy blue livery.

From our position we could not tell exactly what they were doing, other than unloading the lorries, making piles of wood, sand and gravel, and moving furniture in and out of the castle. The furniture that was removed was taken across the lawn to the area that we were soon to know was the old courtyard.

We watched on and off for several days and noticed that many of the original men were replaced by others who were better dressed, walked swiftly, wore skipped hats and saluting a lot. The centre of activity had shifted to the right of the castle where relatively quickly six, single storey, long wooded huts were erected. Soon they were painted grey, totally ruining the landscape.

In a few more days the activity died down completely and all we could see from our hiding place was the occasional movement of sailors between the huts and the castle, and sporadically cars and lorries coming and going. It was about as much fun as watching the gardeners they replaced.

It was just as well that they were gone since the flowerbeds that they had tended had been trampled down during the early days of the naval invasion. Soon they were ripped up completely, filled with soil, rolled flat and generously sprinkled with grass seed.

In a few weeks they became part of the large lawn and a couple of months later, on a Saturday morning, the lawn became a cricket pitch. The Navy had arrived, settled in, and seemingly had time to play cricket.

After a while, watching the activity or more correctly the lack of activity became almost tedious. Even playing in the woods seemed to be less fun with no gamekeeper and dog.

We still however kept a regular vigil, not having that many other things to do. Eventually, and since there seemed to be little danger, we became more daring and ventured from the safety of the trees on to the edge of the lawn.

One day, about three months after the arrival of the Navy, four of us were lying on the grass enjoying the sunshine and watching the clouds sail by.

Suddenly sailors surrounded us; six in all, dressed in Navy Police uniforms with holstered pistols on their white belts. To make them more menacing they carried truncheons. Our passage back to the trees was blocked, and we had no place to run.

We were ordered to our feet, lined up neatly in a single file and marched, I assumed as prisoners, across the lawn and the freshly cut cricket wicket towards the grey wooden huts. We were scared and on the verge of tears, although I thought I saw an occasional smile. Our concerns were made worse when our captors remained silent.

When we reached the second hut we were ushered up two or three steps and through a door into a single room furnished with long tables in a row down the centre.

In the hut were more sailors, about a dozen or so, scattered in twos and threes and sitting on benches on either side of the tables. Some of them were eating, some reading, others talking, and some smoking. As we entered the room they stopped whatever they were doing and stared.

Before we realised what was happening we were directed to sit at one of the tables and given glasses of milk and a large plate of biscuits. The sailors asked our names and ages and introduced themselves, mostly in a variety of English accents that sounded strange to our Scottish ears.

During the next hour sailors came in and out of what we were told was their dining hall — they called it their ‘mess’ even though it looked rather tidy. There were too many of them to remember their names, although they all seemed to remember ours.

After more biscuits and milk we were certain that our capture was in fun and that they were really quite pleased to have us around. One of the sailors from our original escort, a tall blond man with a badge of crossed anchors and a crown on his uniform arm, seemed to be in command. He asked if we wanted to look around. Without hesitation we agreed.

First we saw the rest of the huts. Four of them were sleeping quarters filled with nothing but beds and bathrooms. The fifth was set up as a recreation hall and gym. Then we crossed the lawn to the cluster of buildings that turned out to be the ancient courtyard.

We were surprised that it was so large. It was a cobblestone square with entrances at opposite ends and stables or storage areas on all four sides.

Some of the stable doors were open or missing and were being used as garages for Navy cars. Above the stables was a floor of flats; in use judging by the open windows and curtains flapping in the breeze.

We were given a quick tour of the walled kitchen garden behind the courtyard. Sailors in blue overalls were vigorously tending beds, at least as soon as our escort turned up, that had been dormant for many years. Some of them stopped to say hello, and we left munching fresh but not completely ripe tomatoes.

Finally we got to the castle itself and although we did not see much of it, it was our thrill for that day and many others since to that point we had never been inside, or ever expected to be. Our guide took us through the huge front door into the entrance hall and turned left into the one-time banquet hall, where he pointed out a very wide and high fireplace.

We did not get to go up a sweeping stairway. It was explained that we would see nothing of importance, only office areas and sleeping quarters for commissioned officers. We did meet a few of these officers and were introduced as captured spies.

The officers had even stranger accents than the sailors, and they all sounded alike. Finally, Harry, I think that I remember his name, said that he had to get back to work and he hoped that he would see us again. Little did he know just how often we would turn up.

We made our way back into the woods and wandered home. Later I told my father and mother about my visit to the castle. They paid little attention other than to mutter something about a vivid imagination. Mother did wonder why I did not have my normal appetite. I told her about the milk and biscuits, but did not mention the unripe tomato.

Throughout the war we visited the castle and the sailors very often. We were always welcome, and while we could wander freely we were seldom permitted to enter the castle; but we could visit the mess at will. Over time we got to take part in many of their off-duty activities.

One day a few of the sailors told us that they were going to put on a concert and in next to no time, at the far end of the recreation hall, they constructed a small stage complete with a black curtain.. Rehearsals began in secrecy although we were allowed to watch whenever we wished.

In due course we helped with small chores and soon became responsible for the opening and closing of the curtain and the moving of light pieces of furniture and scenery. When the concert was finally put on, before a packed audience on a Saturday afternoon, we felt very much part of the action.

A regular activity was a weekly cricket match, on Sundays during the summer. The lawn was cut each Saturday and on Sunday morning a wicket was rolled, often with our unneeded assistance, and the stumps set. On the afternoon, weather permitting, the match would take place with almost everyone who was not on duty in attendance.

It really did seem that the crew assigned to the castle were only at war during weekdays. Two or three of us were picked to play on each team.

It really did seem that the crew assigned to the castle were only at war during weekdays. Two or three of us were picked to play on each team.

The MCC would have cringed at the abuse of rules and our Navy did not adhere to an eleven plus one team, unless it was a somewhat serious match against a side from one of the ships in the Gareloch or a deadly serious match against an army team.

Even at my young age I often wondered why the sailors were so nice to us, and again my father provided an answer and he probably got it right.

He said that it was likely that most of them had young children at home and they worried about them and missed them and, this I did not understand at the time but soon did, "You and your friends are who they’re fighting for".

I first wrote about this period in my life many years ago, and at that time I was somewhat surprised that I could remember it in considerable detail. On the other hand it was a major event in my young life and with many diverse things happening it lasted for three years.

By the time I was nine I was developing other interests and visits to the castle were less frequent. Then on VE Day, May 8 1945, the war was called off and I remember during an evening walk along the Clyde Street promenade with my family and many others, seeing bonfires on the hills and being mildly annoyed.

I had always assumed that in time I would be old enough to join the Navy and the battle. I am of course thankful for those who were in the battle and that I never had to.

About the Author

Iain G.Campbell was born in Helensburgh in April 1936 and from age two lived in Ardencaple Quadrant. He attended Hermitage School until his family emigrated to Vancouver, Canada, in 1952. There he spent his working life in manufacturing and logistics management with three multinational companies.

He married twice and has three children from his first marriage. His hobbies include traveling — he has visited 40 countries — cooking and writing. He retired twenty years ago and lives less than a mile from the United States border in the Vancouver suburb of South Surrey. His paternal grandfather owned The Station Bar on Princes Street until his retirement in 1951.