BAREFOOT children on the street, as happened in Helensburgh and district in years gone by, is a sight which exemplifies the squalor and poverty of the bad old days.

There must have been instances where the straightened circumstances of some children left them with little alternative.

Yet it is known from the extremely perceptive and acute powers of observation of Garelochhead man William Hamilton that going barefoot, in summer at least, was the preferred option for many youngsters.

Seemingly they had little thought of this being regarded as demeaning in any way.

Born in 1889 Willie was brought up in the village, and he recorded his memoirs of childhood and youth in a hitherto unpublished manuscript entitled “Memories of a Country Boy”.

Heritage Trust director and local historian Alistair McIntyre, whose hillside home overlooks the village and loch, said: “This is a unique and absolute treasure trove of information, not only about his formative years in the village, but also as a wider social commentary on the life and times of that era.”

Although there is a copy available in Helensburgh Library in West King Street, the manuscript has never been published.

In the early 1990’s, the late Tom Gallacher, ex-Denny’s shipyard draughtsman turned playwright and journalist, presented an overview of the manuscript in the Advertiser, along with a heartfelt plea for its publication.

That call is now being answered by Graham Hamilton, a nephew of William’s, who is actively working to achieve just such an outcome.

The published work will include unique photographs to accompany the text, and promises to be a landmark addition to local history bookshelves.

Alistair gives a flavour of what is to be expected . . .

Willie was born into a family who had been running a thriving joinery business in Garelochhead for several generations. While they worked long hours, they were well removed from a life of poverty.

This is what Willie had to say about going barefoot: “The normal dress for most boys at school was a Norfolk jacket, an Eton collar, and shorts with long stockings.

“But from May onwards, after school and on Saturdays, the majority of boys at school took off their shoes and stockings, and went about in their bare feet.”

While conceding that this made for savings for large families, he continued: “I suppose I would be about ten years old when I started going barefoot, and I looked forward eagerly to getting permission from my mother to be a barefoot boy.

“But a delight it was to have the bare feet on the road and the cool grass underfoot. The roads in those days were stony and rough, very unlike the smooth roads of today, but they were dusty and kindly to the feet, and from June to the end of September were warm.

“We took care to avoid the loose stones. In a few days we got used to it, and the skin on the feet hardened and toughened.

“Sometimes I would get a cut from a broken bottle, and here the remedy was soap and some sugar on a bandage. I would have my shoes on for several days, and then it was back to bare feet again.”

Willie quotes one of his favourite poems, ‘The Barefoot Boy’ by the American poet John Greenleaf Whittier, which ends: “All too soon thy feet must hide, in the prison cells of pride; lose the freedom of the sod, like a colt for work be shod. Ah! That thou couldst know thy joy, ere it passes, barefoot boy!”

Willie had not gone off in a sentimental flight of fancy in his praise of the barefoot condition, as corroboration of his comments can be found in the writings of well-known journalist George Augustus Salsa.

Salsa visited Glasgow in 1866, and left a vivid account of what he saw there, describing scenes from the very heart of the Second City of the Empire in its heyday.

He had rooms overlooking George Square, noticed the number of barefoot people passing by, and spent the next half hour watching them.

He wrote: “I was amazed by the number of persons, mostly young women and children, crossing George Square devoid of shoes or stockings.

“The most curious aspect of this is that in England or on the Continent, bare feet would ordinarily be looked upon as an unmistakeable sign of extreme poverty.

“But the majority of the barefoot lassies we saw were otherwise decently and comfortably clad: petticoats of warm stuff, shawls of bright hues, worth not less than five and twenty shillings apiece, little nattiness in the shape of cuffs and collars, well-parted hair, and even earrings and brooches — but there were the bare legs and feet, not by the score, but by the hundreds.”

Being barefoot might be thought of as a form of liberation, but it enabled a person to move about quietly.

This provides a lead-in to one of Willie’s lifelong interests — his great love not only of the way of life in the countryside, but also of the wildlife and plants to be found there.

The family lived at Oakfield Cottages, nestling by the roadside at the foot of Whistlefield Hill, and across the road was a hay meadow where corncrakes would come to nest each spring.

The males have a loud rasping call in the breeding season, which they keep up morning, noon and night — and William’s Aunt Maggie declared she could not get to sleep once they got going.

Despite the noise, the corncrake is at the same time famously secretive and very difficult to see in long grass, but Willie made it his mission to spot one.

He wrote: “I heard a corncrake some twenty or thirty yards away. I had bare feet, and was walking noiselessly. I advanced slowly and then stopped until I heard it again.

“Once more I advanced a little, then stopped again till it called once more. This went on until I knew I was close, then I dashed forward. There at my feet was the corncrake, flying low and rapidly over the grass.

“It was brown in colour and similar in size to its relative, the water rail. I had seen my first and last corncrake, and I was happy.”

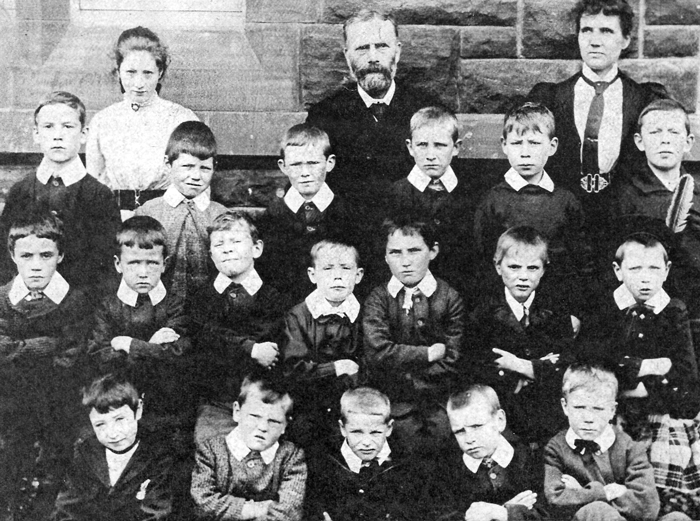

Willie left with a wonderful account of the life and times of Garelochhead Public School. His early years at school seem to have been relatively uneventful, but not so later.

“When I was about nine, I was transferred to the big room where the Headmaster and the pupil teacher, who was actually his eldest daughter Nan, taught,” he writes.

“The big room was divided by a sliding partition, with the Headmaster in one section.

“One day, sitting at a double desk, I noticed the girl alongside had the skin peeling from her fingers, and I wondered if it might be scarlet fever.

“Some days later, my brother John was taken to Helensburgh Fever Hospital, and I learned there was an epidemic.”

A few days later. William also fell ill, but soon recovered, although his sister Barbara had to be taken to hospital. In due course, normal life resumed.

Willie continued: “Each morning, the sliding partition was pushed back, and the Headmaster took over.

“After a prayer and reading from the Bible, he produced the Scotsman newspaper, and read the leader to the classes.

“Then he would discuss what it meant, and any unusual words were written on the blackboard. He would ask a scholar to spell them, and give their meaning. The sliding doors would then be closed and classes would proceed with the syllabus.

“John Connor was the name of our Headmast, and he came from Northern Ireland as a small boy.

“He trained as a teacher at the Free Church Normal College in Glasgow, and afterwards spent short periods in some schools near Edinburgh.

“Later he came to Larchfield School in Helensburgh. After four years there, he was appointed Head at Garelochhead in 1874.

“He was of medium height and stocky, and always wore a brown beard and had bushy eyebrows, with pale blue eyes that looked at one with a glint of humour in them, and that steadfast gaze of one who had spent a lifetime in observation of human nature.

“I can see him sitting at his desk examining some papers, and now and again glancing sharply round the room.

“He would detect some furtive movement, and would saunter up between the desks — then suddenly a boy would receive a cuff on the ear, and he would say ‘Put that away!’

“The boy knew full well he had deserved it. He had a stout cane which he would use on occasion. He gave you one, two or three on the palm of the hand, and, believe me, they were no gentle strokes. But no damage was ever done.”

Willie obviously thought very highly of his old headmaster, and said of him: “Mr Connor was one of the old-time dominies, now alas long extinct, but who made Scottish education known throughout the world.

Willie obviously thought very highly of his old headmaster, and said of him: “Mr Connor was one of the old-time dominies, now alas long extinct, but who made Scottish education known throughout the world.

“His pupils could never argue that they had learned little from him. He was a born teacher of above average intelligence, and what was equally important, a public figure taking part in all things pertaining to the welfare of the community.

“He could have gone to larger and more important schools, but he preferred to stay in the village where he was esteemed by all.

“His wife and family of eight were refined people, and I got to know them well.

“He lost his eldest son John, and his youngest, Norman, in the First World War, and it is doubtful if he was ever the same man afterwards.”

Mr Connor retired in 1910, when his place as headmaster was taken by William McLatchie, formerly of Clyde Street and Grant Street Schools in Helensburgh.

Another occasion when bare feet were not in evidence was of course each Sunday, when best clothes were the order of the day for Church and Sunday School.

“Everyone dressed in their best, which was very good," Willie said. "Most men and youths wore blue serge suits or a good tweed, and starched linen collars were the rule.

"The women mostly wore costumes made by dressmakers, with bodices that fastened at the back — with a frill of lace at the neck and on the cuffs. They wore hats of various shapes, and these were decorated with flowers or bunches of fruit, and of course their faces were covered by veils.

"Girls wore flouncy multicoloured dresses of becoming shape and appearance.

“The Church did not go in until noon, and in spring and summer it was usual to take a short walk along the burn and gather flowers before preparing for church. All play was frowned upon, but one could walk in the fields or by the burn and observe wildlife, or sit down and read a book.

"The Sunday School lasted until two o'clock, and after lunch I would take a walk with my father. There was church again at six o'clock, but I don't think I went until I was older “

Two churches then existed in the village: the Established Church and the Free Church (United Free from 1900). Another snippet from Willie — the church officers would meet before Sunday worship to synchronise watches prior to ringing the bells.